NEW YORK—Some of life’s tests you can’t study for: certain computer science exams at Harvard, hearing tests, tests of character. If I had something profound or insightful to add to this list, I would. But all my summer has given me so far is this: also, drug tests.

The package, mailed from the corporate headquarters of the company I’d be interning for, arrived at 11 a.m. on the Saturday prior to my Monday start date. At first, I was annoyed that my mother had woken me up (on the grounds that there exist implicit “do not resuscitate” orders for kids who’ve just returned from college). But then I was grateful: the paperwork enclosed in the package said I had to complete the drug test within 48 hours.

The weekend hours of “Quest Diagnostics,” my designated testing center: Saturday, 10-12:30. Sunday, Closed. It was already 11:30. I had an hour. I grabbed a water bottle and was off.

I added my name to the unnervingly long sign-in list and greeted the unhappy-looking receptionist. It isn’t easy to be a receptionist at a “Quest Diagnostics” in Queens, NY. Sure, it’s not the hardest job in the world—that’s what those Alaskan king crab fishermen on “Deadliest Catch” do. But “Quest Diagnostics’ receptionist” in Queens is up there.

It’s not so much the daily interaction with parolees and little snot-makers carrying who-knows-what kinds of communicable diseases that makes it hard.

It’s having to pronounce the names.

New York City’s largest borough is also the most ethnically diverse place on earth. This makes for an excellent variety of cuisines, from “Mama’s Empanadas” to “Knish Nosh” to the less clever but no less descriptive “Himalayan Yak Restaurant.” It also makes it fun to ride the subway and smile/frown/raise your eyebrows as you pretend to understand whatever language the old men across from you are speaking.

But Queens’s diversity also makes for a complicated variety of spellings and pronunciations. The receptionist seemed apprehensive every time she looked down at the sign-in sheet, full of alien consonant combinations and intimidating lengths. At 12:15 she tried mine: “Moglinski?” Close enough. I rose to hand in my paperwork, channeling Michael Parzen as I thought: “Let’s get this over with.”

“You’ll have four minutes to fill the cup to the line,” said the nurse who administered my test. He handed me a small key and told me to put my belongings in the metal lockbox on the counter.

“Are you ready to go?” It seemed a little soon to be talking about such intimate bodily functions, but I told him yes.

That turned out to be the wrong answer. I couldn’t produce a large enough sample. “Of course, contraction of the involuntary sphincter is part of the autonomic nervous system’s response to stress,” my neuro-anatomist mother would later say. Yes—of course. At the time, though, all I could think was “Oh my god, oh my god, I’m going to fail.”

I made myself decent and opened the bathroom door to ask the nurse if the pathetic volume would be enough.

He laughed. “THAT? Nope.”

“Oh my god, I’m going to fail, aren’t I?”

“Well, you have one minute left, try to go!”

I tried. I couldn’t. I was struggling to recall the details of the commencement speech J.K. Rowling gave in 2008, the one about how failure is good for you, when the nurse knocked to signal that the four minutes were up.

I had one more chance, he said, but I’d have to start over. “And technically we’re already closed, so you’d better be fast.”

And then I drank more water than I ever have in my life. Having locked my water bottle in the metal box, I had to stand next to the cooler and keep refilling a four-ounce paper cup. I don’t know how much I drank, but my stomach already felt fit to burst when I noticed that a kid next to me seemed to be having a similar problem. “Keep going,” his dad insisted. “Don’t be a wimp.” At least I’m not a wimp, I told myself. Then again, that kid probably wasn’t at risk of failing a drug test.

Feeling painfully bloated and a little ashamed, I considered what my own father would have told me had he been there. “I think you should keep drinking,” he’d have said, even though he’d have really meant, “I don’t believe in weakness.” I sighed and refilled the sad little paper cup.

“Mojaluski?” said the receptionist. It was 1 p.m. Do or die. Urinary bladder, don’t fail me now, I thought as I hobbled to the bathroom.

Then I did it. I filled the cup to the line. I high-fived the nurse (after he’d poured the sample into a plastic test tube) and left “Quest” feeling victorious. I only made it about a third of the way home before remembering that I’d left my wallet, phone, and keys in the aluminum lock-box.

I will spare you the details, but I could not venture far from the bathroom for the rest of the day. Hours later, as I lay on the couch feeling lightheaded and uncomfortable, my dad said, “That’ll teach you not to drink so heavily.”

Read more in Opinion

The Indian in Old Town SquareRecommended Articles

-

O'Donnell Too Small for Hemingway's ShoesWhile several conflicting theories may exist about the relative importance of this or that long-term cause of World War I,

-

Hussain Denies Rape Charges in TrialDespite three and a half hours of sometimes heated questioning by the prosecution, a composed Dr. Arif Hussain yesterday testified

-

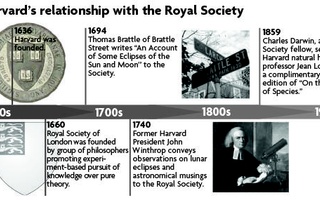

Royal Society President Calls for Integration of Science and Policy

Royal Society President Calls for Integration of Science and Policy -

From Cannes: "La loi du marché" ("The Measure of a Man") Comes Up to ScratchIn our continuing coverage from Cannes, Tianxing Lan examines Stéphane Brizé's soul-crushing drama about a man cornered by his economic circumstances, "La loi du marché" (English "The Measure of a Man").

-

En Boca: Eat Average Food, and Go Broke While You’re at it

En Boca: Eat Average Food, and Go Broke While You’re at it