The winds of change howling through the world of sports safety have become impossible to ignore. Traditional football has nearly been toppled by the gusts, and the winds’ next victim, hockey, lies just around the corner. Adding to the drafts is none other than our little Ivy League.

The breezes began back in 2009, when the NFL was called out by Congress for not adequately protecting its players from the dangers of concussions and other head injuries.

Before the hearing, the most popular American sport considered it manly and honorable to go back into battle after suffering a concussion, and players were only held out of the game if they lost consciousness. That kind of irresponsibility would no longer be tolerated—or so we thought.

When NFL players entered the stadiums to kick off the 2010-11 season, they left progress at the door. In week one, Eagles head coach Andy Reid sent Stewart Bradley back into a game against the Green Bay Packers after the linebacker took a hit to the head, attempted to get back up, and then stumbled and fell right back to the turf.

Things only got worse from there. Finally, things hit a tipping point in week six, as an embarrassing number of vicious hits, including two by Pittsburgh bad boy James Harrison, led to the uproar necessary for the league to institute real change. Heavy fines were instituted, and common sense employed. The gusts could not be ignored. Change was in the air.

In college ball, it was none other than the Ivy League that stepped up first and began to seriously address the issue. Before the 2011 season, the Ancient Eight became the NCAA’s progressive conference by instituting a number of rule changes to limit hits in practice.

But there is still plenty of work to be done.

The recent suicide of Ray Easterling – one of several former NFL players suing the league– as well as an increasing wealth of scientific evidence on the effects of football hits on kids in high school and Pee Wee Leagues are signs that we need to further investigate how to make the sport safer and help those who have been damaged for our entertainment.

Though the Ivy League doesn’t carry much weight as a minor FCS Division I conference that doesn’t compete in postseason play, its alumni wield great power in other fields. The Big East or Pac-12 might not follow the lead of a Harvard or Penn on the football field, but Harvard graduates have the capability to lead in their areas of expertise.

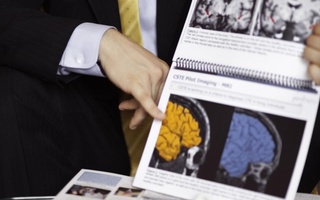

Former Crimson football players Chris Nowinski ’00 and Vin Ferrara ’95 provide strong examples of what can be done. Nowinski has established himself as a leading activist, while Ferrara has set out to design a better football helmet. Harvard graduates in government, science, and education should follow Nowinski and Ferrara’s lead.

In contrast to the impact of its new policies in football, the reaction to the upcoming Ivy League rule changes in hockey, lacrosse, and soccer may be more immediate and more widely felt. Harvard and other Ancient Eight schools are Division 1 competitors in most of these sports and members of the sports’ top tiers in some cases.

But while the dangers of concussions in football have been covered on front pages since 2009, concussions in hockey, lacrosse, and soccer have not seen the same amount of coverage. That means that when the league’s concussion committee presents its findings and recommendations, it could spark a much-needed discussion about safety in the three sports.

The sport most in need of a shift in philosophy is hockey, and it’s not even close—a fact the NHL playoffs have made disgustingly clear. Nearly every series has seen its share of illegal and dangerous hits to the head, including concussive blows to a number of key players.

Earlier this year, a Philadelphia Flyer hid his concussion for fear of looking like a wimp and a freeloader while vying for a job. More unfortunate than that though, is the admiration he received for being a “tough guy.” I’m confident that in five years, actions and reactions such as these will be looked upon as savage, but we can’t let time fight our battles.

Amid the embarrassments, good signs can be found. When a Toronto Maple Leaf similarly hid concussion symptoms, he was lambasted by the team’s GM, Brian Burke, and Penguins superstar Sidney Crosby was seemingly given all the time he needed to return from concussion symptoms. These may be signs of an oncoming windstorm of change.

Blown stronger by the upcoming actions of the Ivy League, the winds may soon whistle past NFL stadiums and up against the machismo of the NHL, not relenting until much-needed progress arrives. But there is still a long way to go, and the Ivy League’s upcoming statements will only be the beginning of a long and arduous process of change.

—Staff writer Jacob D. H. Feldman can be reached at jacobfeldman@college.harvard.edu.

Read more in Sports

Minnis Forges Unlikely Path to HarvardRecommended Articles

-

Confronting the Concussion

Confronting the Concussion -

Concussed: Down and Out

Concussed: Down and Out -

Panelists Discuss Head Trauma ResearchThree panelists described current medical research and long-term goals to reform care and policy on athletic head trauma and concussions during a biannual symposium of the Harvard Society for Mind, Brain, and Behavior in Science Center C on Friday afternoon.