Silk dress, dove gray, fifty years old and sixty dollars. Little vintage store in Boston. Think transatlantic Sylvia Plath around the time she bit Ted Hughes’ cheek. Think sexier “His Girl Friday.” I fucking loved that dress. Pepper-hot hole burning in my freshman-year checking account from writing money—I had to have it. I nabbed it, brought it home, and wore it to the literary magazine open house, covering my torso with silk and my nervousness with lipstick.

I came to Harvard because it felt hostile. And it felt hostile, mostly, because of how it looked: stained glass windows, heavy spires, thick oriental rugs. I was eighteen years old and bursting the seams of my small town, having outgrown its ugly linoleum-halled high school and muddy, Confederate-flag-strewn pickup trucks. Harvard seemed big. Harvard seemed evil. When I walked through the Yard one October morning, a girl in red lipstick, black skinny jeans, and black heels power-walked out of Weld looking sexual and important. On a Wednesday. Harvard was mean because Harvard was aesthetic, and I, said the admissions committee in a fortuitous letter in late April, was Harvard.

But I wasn’t, or, at least, I didn’t feel like I was. I feel like a lot of us never really do. We can all name articles of clothing, architecture, and décor that form the “Harvard aesthetic”: pastel shorts, Memorial Church’s bell tower, Sperries. As a freshman, these things terrified me; they still frequently terrify me. The Lampoon steps, the Barker Center carpets, the Law School leather couches, the Annenberg rafters and the plush interior of the Spee—the objects of daily life—were constant reminders that I had no idea what I had gotten myself into. Harvard aesthetics are about a sense of continuity: that awe you feel when you walk into Sanders; the feeling that JFK and Thoreau are just around the corner, at an ornate defunct fireside, having a chat. But we’re not all Teddy Roosevelt, and the aesthetics of continuity are also continuous with an exclusionary past. For those of us who feel structurally alienated in whatever way from this past, or for whom the Harvard aesthetic isn’t contiguous with our personal pasts, aesthetics can have an intimidating, exclusionary bite. And more than that: The aesthetics of a place circumscribe its occupants, enabling certain forms of being, certain modes of thinking, and excluding others. How can we be productive, then—not to mention happy—when surrounded by social and aesthetic modes that in some way reify our exclusion? How can we think exciting, gutsy, radical, rebellious thoughts when constantly elbowed by the big guys of the past?

An example of how complex this is: The fall of my freshman year, I was part of a discussion group dedicated to analyzing these very issues. We met once a week to talk about identity and power, about social stratification and social space. Of all places, we did it in the Coolidge room. The Coolidge room is in Adams House, and it looks like an Abercrombie showroom: walls festooned in a mural of the muscular collegiate gentlemen of Harvard past. None of us looked like anyone pictured in the murals; sitting there felt like wearing someone else’s outgrown suit. How did our surroundings suggest the ways we could or could not be, the things we could or could not say?

There is incredible vitality in the promise of diversity. We are, as collections of individuals, more original and thrilling, more productive and messier, than the tradition in which we are placed. And there are ways to facilitate this creativity. First of all, we can fight for spatial affirmations of human diversity against histories of exclusion: this is why spaces like the Harvard Foundation for Intercultural and Race Relations, the Women’s Center, and the Office for BGLTQ Student Life are so important. Second of all, we can fill spaces with possibility models. The Harvard Foundation Portraiture Project, for example, does just this. In commissioning paintings of people of color who’ve had substantive roles in Harvard’s history and hanging them in campus space, the Project subtly changes the archive of each building’s interior. It’s powerful to see someone who looks like you, or to have space specifically welcoming to people who identify as you do, on this campus.

As a senior—even as one who’s done her fair share of walking through the Yard in heels—I think a lot about me at nineteen, at that open house, terrified in that scrap of silk. We live in a community deeply and ostentatiously circumscribed by Tradition, capital T: It’s built into the walls and hangs adorning them; it structures our course loads and social lives. I want to think critically about the materiality of that tradition, and how we can intervene to make this an enabling, justice-oriented space. How do the confines of these rooms shape the confines of our imaginations? How do we open up the library windows, fling open the gates, tempt a crossbreeze as wide and wild as ourselves?

Reina A.E. Gattuso ‘15, an FM editor, is a joint literature and studies of women, gender, and sexuality concentrator in Adams House. Her column appears on alternate Fridays.

Read more in Opinion

The Difficulty of Defining DifficultyRecommended Articles

-

Four New Full Professors Named In Philosophy, English, MineralogyAppointment of four members of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences to full professorships was announced by Dean Bundy yesterday.

-

Aesthetics and AcademicsMaybe someday, “aesthetics” can even be another category in the Q Guide.

-

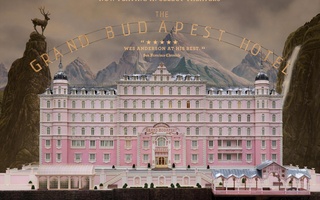

The Other Wes Andersons

The Other Wes Andersons -

Faculty Approve General Education Overhaul

Faculty Approve General Education Overhaul -

Webcomics, Macro Memes, and the Continued Destruction of Things Highbrow"Breaking down the myth of things highbrow doesn’t just have to do with what gets put in museums. It has to do with empowering disenfranchised voices."