{shortcode-df130a3bc046ba28afd32b7c05c97d8ba42a4e19}

As with many Harvard students not from New York or overseas, one of my first impressions of Harvard Square was its walkability. With all its shops, cafes, and restaurants, so close together, with relatively narrow (and often one-way) streets and bike lanes galore, the Square felt like a page from a post-Jane Jacobs urban design textbook had come to life.

Then, I went to the other Cambridge.

During my semester studying abroad at Cambridge’s Jesus College, I certainly noticed the bikes: one in three adults bike five times a week, the highest share in the United Kingdom. But I barely noticed how easy it was to walk around the city center — how I never had to weave in between cars stuck in traffic or jog across a street to avoid a speeding driver. In fact, I rarely had to wait more than a few seconds to cross.

Upon my return to Harvard’s campus this summer, though, these differences were no longer “99% invisible.” My commute from 29 Garden Street to Radcliffe Yard, so simple on paper, involved multiple perilous crossings of four-lane streets with speeding cars and confusing stoplight patterns. When the school year started, I noticed more pedestrian-unfriendly crossings, particularly on Massachusetts Avenue, which most students at the College cross every day.

No, I’ve never been hit, but many are not so lucky: About 90 pedestrians and bicyclists are hospitalized by car crashes in Cambridge each year. And the symptoms of pedestrian- and cyclist-unfriendly design extend beyond safety. By discouraging Cantabrigians from biking or walking, this planning encourages them to drive (or ride-share) instead, stuffing the roads with cars. As a result, those who commute through Cambridge sit longer in traffic — not only wasting time but reducing commuters’ physical activity, worsening air quality, and emitting more planet-stifling carbon. Finally, by worsening walkability, one of the most appealing aspects of urban life, and making longer, car-based commutes easier, car-centric design incentivizes those who can move to the suburbs to do so, with terrible consequences for racial integration and public finance.

The instinctive response of cities to clogged streets for a century has been to focus on improving traffic flow — to widen the streets, eliminate crosswalks, add more complex traffic light systems like left-turn arrows, and, where possible, increase speed limits. In other words, we’ve sought to make it easier to drive. But anything that makes it easier to drive has the same ill effects as discouraging walking or biking. In fact, you might notice that the elements that make driving easier are the same as those that make walking harder.

This is no coincidence. All forms of road transportation compete for space, but cars’ spatial inefficiency (especially single-occupant cars), speed, and weight make them particularly adversarial and dangerous to the rest. As a blog post titled “How Much of Making Transit Easier is Making Driving Harder?” argues, making cities more car-friendly necessarily makes them more hostile to other (safer, healthier, greener, more efficient) forms of transit — and vice versa.

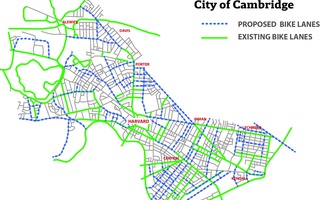

Luckily, Cambridge has already taken significant steps to return its streets to non-drivers, with an ambitious plan to add 16 to the city’s 25.8 miles of bike lanes by 2030. In summer 2017, the city removed a lane from the stretch of Brattle Street in front of the American Repertory Theatre and added a protected bike lane in each direction. The result, a vastly more bikeable and walkable neighborhood, represents a model for cities everywhere.

But humbler and simpler redesigns could also make the Square more pedestrian-friendly. For example, the curb extensions on Mount Auburn behind Oberon make Mather residents’ walk to class safer and easier. The city should add curb extensions westward on Mount Auburn and a few on Massachusetts Avenue, say, in front of the Harvard Bookstore, Clover, and Waterhouse Street. This would sacrifice one or two parking spaces each.

More recently, a “sudden inundation” of dockless electric scooters in Cambridge pushed questions about street design to the public forefront. I am quoted in The Crimson’s article about the city’s response as saying that “scooters represent a potential to continue moving away from cars and toward more sustainable and more spatially efficient ways of getting around the city.” For lack of space, the rest of my rant to the reporter was understandably cut. Suffice it to say that as Cambridge expands bike lanes, which seem like a better fit than either roads or sidewalks for the 15-miles-per-hour scooters, the advantages of this cheap, compact, clean, quick, and low-effort form of transit will become even clearer.

To that list of adjectives, I should add “safe.” Some complaints about scooters dress up a fear of change or hatred of anything that smells like Silicon Valley in safety concerns. Such complaints are, always, statistics-free. When one man died this week in a dockless scooter accident, bringing the all-time total to two in tens of millions of rides, it made international news. (Assuming the day of the man’s death was an average day in traffic deaths, about 80 people died in car accidents!) By allowing Cambridge commuters to take Birds instead of Ubers or their own vehicles, we would be allowing a shift to a much safer form of transportation. Critics also worry about the effects on accessibility, but as a Crimson staff editorial recently noted, scooter companies have already taken steps to address these concerns — and a reduction in the car traffic that sends us scurrying across Mount Auburn would no doubt make crossings easier for pedestrians with mobility problems.

In the century following the Model T, cities across the country, including Cambridge, redesigned themselves to be as car-friendly as possible. With a few miles of bike lanes and a handful of Birds, Cambridge has only begun to reverse this environmental, sociological, and public health catastrophe. Here’s hoping they keep biking down that path.

Trevor J. Levin ’19, a former Crimson Arts Comp Director, is a Social Studies concentrator in Mather House. His column appears on alternate Mondays.

Read more in Opinion

A Drag Into the 21st CenturyRecommended Articles

-

Bike Lane Advocates Crowd City Council MeetingDozens of Cambridge residents advocated for building more bike lanes around Cambridge at a City Council Monday.

-

Cambridge Officials Encourage More Bike InfrastructureCity officials and activists gathered in City Hall Wednesday to discuss bike safety in Cambridge.

-

After Fatal Crashes, Cantabrigians Debate Bike Lanes

After Fatal Crashes, Cantabrigians Debate Bike Lanes -

Adriane Musgrave

Adriane Musgrave -

Cambridge Ponders Electric Scooter Program After Unexpected Summer 'Flock’ of LimeBikes and Birds

Cambridge Ponders Electric Scooter Program After Unexpected Summer 'Flock’ of LimeBikes and Birds