{shortcode-7ff56c0bd014e30a1a1274482993d653ef5b0781}

{shortcode-8c0dd475ea3269f67b1a4d37d27db5cc232a1fc2}hen Ava E. Silva ’27, a Crimson Arts editor, gave a presentation to the Harvard Undergraduate Linguistics Society about Alabama, an endangered language of the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe, she asked her grandmother to record a short video introducing herself in the language.

Silva’s grandmother — or áapo, in Alabama — sent back a two-minute long video, but it didn’t exactly follow the script Silva had given her. Curious, Silva asked her áapo what she added. The gist of it, Silva says, was “no one cared about our language for a long time. My granddaughter is bringing it back.”

With a few hundred native speakers, Alabama is a dwindling language, particularly for the younger generation. Silva’s áapo grew up only speaking Alabama until she began elementary school, where she was both forced to learn English and punished for speaking her first language. Because of this, Silva’s áapo didn’t teach the language to her children.

When Silva came to college, she was set on studying Government. Interested in preserving endangered Indigenous languages, like Alabama, she joined the Harvard Undergraduate Linguistics Society after learning about it at the linguistics booth during an academic fair.

Silva’s presentation to HULS marked the beginnings of more expansive work in language preservation at Harvard. After her presentation, she became involved with the Working on Language in the Field (WOLF) Lab. Led by principal investigator Tanya I. Bondarenko, an assistant professor of Linguistics, this newly established lab conducts fieldwork on understudied and under-documented languages.

Within the lab, Silva and a team of Harvard researchers are currently developing the Alabama language project, a five-year initiative that aims to document the language, study its grammar and lexicon, and produce educational resources for the Alabama-Coushatta community.

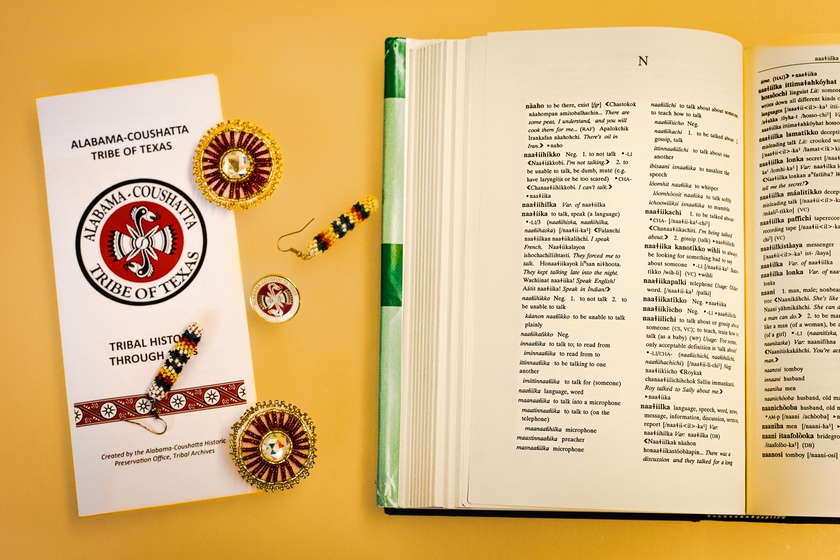

In January, Silva, Bondarenko, and freshman Ph.D. student Jacob A. Kodner traveled to the Alabama-Coushatta Reservation in East Texas to discuss project plans. The team met with both Alabama speakers and non-speakers, gauging the tribe’s needs and desires. For example, members of the tribe talked about an Alabama-English audio dictionary and curating learning materials for a planned education center.

For Kodner, the winter break trip was “one of the most profound experiences I’ve had in my linguistic career.” He sees the project as an opportunity to combine the more traditional aspects of linguistics — data collection and theoretical study — with community-oriented education.

Rather than vocabulary lists and rote memorization, Kodner explains, a linguistics-based curriculum for Alabama would focus on how words are structured. “If you learn the building blocks of a language, you can create, for example, an infinite amount of combinations in the language,” he says. “It creates more opportunities to really engage.”

More than anything, however, this trip was about forging a connection. “We didn’t do a lot of fieldwork, because our main goal was just to talk to the community,” Silva says. The tribal council approved the project, giving WOLF the green light to return for further fieldwork in the upcoming summer and winter.

The winter break trip helped WOLF outline its more immediate goals: a grammatical sketch of Alabama, a basic curriculum, and a linguistics workshop for interested community members. “The Alabama language is very endangered, and so contributing to preservation efforts that would benefit the community is definitely our top priority,” Bondarenko wrote in a statement.

Each week, the project holds seminar meetings, where members of the growing research team take turns presenting a paper on a linguistic subfield, such as syntax. The group then applies linguistic theory to the Alabama language itself and transcribes audio clips collected during the January trip.

Academic research on Alabama, however, is scarce. For the project’s first seminar, the team read a paper published in the 1980s about Alabama’s phonology. “It was written on a typewriter, if that says anything,” Silva says.

Kodner hopes that the discoveries in studying the Alabama language will contribute to the larger field of linguistics, particularly morphology, or the study of how words are formed.

“There’s not much information about the morphological processes in the language,” Kodner says. “I definitely think there’s not only a lot to discover, a lot to develop materials around for the community to document, but also a lot that can offer to the study of language itself.”

Any language data the lab collects, however, will belong to the Alabama-Coushatta tribe. All of WOLF’s outputs will be shared with the community, and any academic findings will be published in open-access venues. The emphasis on information sharing comes at the heels of apprehension raised by the community. “A big concern for the community was is this going to be kind of an exploitation,” Silva says. “Especially because people have come in and worked with our tribe before, and then they promise so, so much.” She isn’t sure how many people in the tribe know about previous academic scholarship on the Alabama language.

Silva sees herself as a “middle-person” in this project, connecting the researchers at Harvard with people in her community. “I’m always going to be on my tribe’s side,” she says. “There’s no room I’m going to be in where I’m going to advocate for Harvard over my community.”

In the lab, Silva occupies many roles: she is both a liaison to and an advocate for her community, both a peer of graduate students and a freshman taking Ling 83, Harvard’s introductory course for linguistics. “Definitely it’s daunting sometimes,” she says.

“My community is kind of on my shoulders,” Silva says. “And I’m in Ling 83. I’m not some linguistics expert.”

Even if Silva sometimes feels that linguistic skills do not always come naturally to her, the “curiosity and passion” do.

For her, work in the lab goes beyond the theory. “When the language touches my ear, it’s just like a hug,” Silva says. “It’s been amazing to not only learn the language and get to hear the language and just have the language be a part of my weekly life, but also learn from elders.” During the lab’s winter trip, they began to learn new stories about Alabama history as elders opened up about their native language.

“They didn’t want to teach [Alabama] to their kids. They didn’t want to talk it because they grew up with so much pain with it,” Silva says. “And now, they’re like, ‘oh, my language is beautiful. I want people to know it.’”

Silva hopes that her work in the Alabama language is a stepping stone for further language documentation in Indigenous communities. “Language preservation represents, as a whole, Indigenous futures,” she says. “And I think that’s something Harvard can and should continue to learn from. My number one goal is working for my community, but also my community means Indigenous populations in general.”

— Magazine writer Maeve T. Brennan can be reached at maeve.brennan@thecrimson.com.