{shortcode-111db410b63196c995d430fa91cd95f8ab741f30}

Content warning: Descriptions of depression, anxiety, and other mental illnesses and psychiatric conditions; descriptions of drug use.

As we sat in Harvard’s Currier House dining hall for a fifth consecutive hour — the frenzy of lunchtime falling into a midafternoon lull and the days we had planned unraveling, classes and meetings missed — our conversation about our experiences with psychiatric drugs engulfed us. Questions long festering in our minds entered and thickened the air between us, and our search for clarity yielded only more confusion.

How can we — how should we — make sense of the psychiatric medications in our bodies and the experiences, feelings, and thoughts they engender? The practice of fine-tuning our minds to best fit the shape of our lives... is it a good one? Does it obscure our “real” selves?

We joked about eventually writing this piece, and about how we were part of some secret magic pill club. We discerned that every day, between the two of us, we take up to 448 milligrams of medication: antidepressants, anxiolytics, stimulants, and relaxants. But the jokes felt less like jokes as time went on. We hadn’t anticipated just how difficult these questions would be to ignore, or how much we’d been craving the community we found in our conversation.

Psychiatric medication warps our experiences and those of many of our classmates, and in recent years, the use of these drugs has risen. Between 2007 and 2019, the proportion of American university students taking the most commonly prescribed antidepressants has nearly doubled, from 8 percent to 15.3 percent. Rates of depression in college students have similarly surged, from 17.4 percent in 2013 to 40.8 percent in 2021, and rates of anxiety have doubled.

Yet there is no Magic Pill Club, and the phenomenon of using psychiatric drugs remains largely unscrutinized, piercing the social fabric only through isolated conversations and errant private social media posts.

So we set out to document and better understand this aspect of living with mental illness, seeking answers to the questions brought to life in Currier’s dining hall. We conducted a dozen interviews with students taking psychiatric medications and experts across various disciplines. The process was turbulent, dragging us through sometimes painful memories and realizations. It challenged our conception of ourselves and our medications, in turn surprising us, enlightening us, and leaving us in tears.

We found no definite answers.

Researchers have established that psychiatric medications alter levels of neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine in the brain. They’ve also shown the medications can relieve mental and emotional distress for some patients. But the link between how these drugs work and why they can be effective eludes modern psychiatry, as does a complete understanding of what causes mental illness. Some patients aren’t helped by psychiatric drugs, and many are left struggling.

Interviews with students about their experiences with medication did not cohere into a real answer either. One described their medication as stripping away their basic humanity, another as restoring them back to themselves, and yet another as providing nothing more than a gentle boost.

Still, we did discover something, laying the conversation we began months ago to rest. It didn’t answer our questions, but it quieted the anxieties behind them, providing new ways to understand our experiences.

The perseverance of students and spirit of psychiatrists — often forced to confront the blank face of uncertainty — wove together into a tapestry of resilience, one at once tattered and perfect, inspiring and incomplete.

The Crimson offered anonymity to all of the students mentioned in this piece due to the sensitive nature of their psychiatric and medical experiences. All names in this piece, unless accompanied by a surname, are pseudonyms for Harvard College undergraduates. This choice was made to aid readability and to humanize the subjects of this story.

‘To Not Feel Awful’

KSG & GRW: Hannah began taking Zoloft — a type of antidepressant called a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, or SSRI — during the summer after her senior year of high school.

Her decision followed protracted struggles with mental health. She developed anxious and obsessive thoughts sophomore year of high school, and depression years later. Throughout, she was hesitant to consider her mental state abnormal and grappled with questions about whether her suffering was an inevitable part of her life.

The pandemic saw Hannah’s struggles increase exponentially, especially by her senior year. “During the pandemic, honestly, I would say I cried every single night, for hours,” she says. “And that’s just not a normal thing.”

At the time, “I didn’t really realize how wild that was or how not okay that was until after,” she says.

Hannah says her psychiatrist “isn’t someone who’s very drug-heavy.” And Hannah’s mother had always been hesitant about medication. But it was actually her mother, seeing how persistently miserable her daughter was, who recommended that Hannah consider psychiatric medication. Hannah says that starting Zoloft “wasn't really that hard of a decision.”

“I was kind of feeling awful and wanting to not feel awful,” she says.

It wasn’t as though she started feeling better right away, she says, but she noticed little things that built up: She cried significantly less, she felt more confident, her obsessive thoughts weren’t all-consuming, and she talked to new people without paralyzing anxiety.

But Hannah still grappled with the implications of these improvements. This past summer, while reading “Brave New World” — a novel in which characters take a drug called soma that makes them happier and distracts them from issues plaguing their dystopian world — Hannah thought to herself: “Am I doing that? Am I ignoring things?”

Hannah used to dream of being a writer. She thinks part of why she wanted the career is because she felt her emotions so intensely. She remembers thinking: “Life sucks. What am I going to do with this if I’m not writing about it?”

Before she began taking Zoloft, she asked her therapist if it would make her a different person. Her therapist said no — the medication would just make things less extreme, like a cushion. That rings true to Hannah’s experience: Zoloft isn’t soma, she says. She doesn’t think she’s lost the thoughtful or emotional aspects of herself — the intensity with which she experiences the world has just lessened.

Hannah believes the question of whether medication obscures the “real” self underneath isn’t the most relevant: “Does it matter if you’re yourself if you’re miserable?”

‘Giving Myself Away’

KSG: I am a crier — I’ll admit it. I teared up when Hannah asked if it matters if you’re yourself if you’re miserable, because it felt like she was posing the question directly to me.

Like Hannah’s, my road to getting on antidepressants was winding. Early in the pandemic, I remember telling my therapist over FaceTime that I felt more like myself when I wasn’t happy.

“You really think happiness is the point of life?” I asked her derisively. “I don’t want to be happy. I wouldn’t be me.” And then there was the matter of my creativity, the words that felt like a lifeline when I couldn’t find meaning in my day-to-day. “I can’t think of a single great writer who was happy. Can you?” I asked. I might have stumped her there. I switched therapists not too long after.

I have never met anyone like the psychiatrist I have now. She is feisty, white-haired, and spry; she refuses to medicate patients without also being responsible for their psychotherapy; and she was the first person who saw with clear eyes how much I was hurting.

I went to see her for the first time around a year ago. Light filled her living room; the space responds acutely to the weather outside, I’d come to learn. I associate her with yellow. It is the color of her house and her most often-worn sweaters.

When I sat down shivering in the chair across from hers, I spoke for nearly two hours. First, I told her the bare facts of my story: my parents’ divorce, coinciding with the start of the pandemic. A relationship-that-never-was the summer of 2020, which left me a shell of myself when he left for college. How I’d end most nights that fall tangled in tears and sweaty sheets in my bed — I could never quite tell which salt I was tasting. How I took to crying on the floor of my shower during the winter and the floor of my kitchen in the spring.

I suppose on some level, like Hannah, I knew it wasn’t normal. But sometimes it’s really difficult to figure out what isn’t until after the fact.

I told her how, in the summer, I decided I was done with that high school shit, I was done being a pathetic mess who couldn’t sort out the air in front of me enough to figure out what was real and what wasn’t. Things were better, now that I was at college — college was fixing everything. That was what was supposed to happen, right?

I was having hours of anxiety-induced chest pain a day, of course, and I felt like my life was happening behind a sheet of glass. But I was trying, I really was. I needed her to understand that I was trying so damn hard.

She did understand how hard I was trying, perhaps more than anyone ever had. But she also wondered why I thought life was supposed to be like this.

“Are you happy?” she asked.

“No,” I said.

“Why haven’t your friends or family told you to get help?”

“Well, I’m really very high-functioning,” I told her, “it’s not like my grades have slipped or anything.”

“Do you think you might ever be happy again?” How could I say no without giving myself away?

By the end of the session, she’d diagnosed me with generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. Those words terrified me — do diagnoses make things final? They were also a second chance I never thought I’d get, a way of containing the overwhelming feeling of gray I thought would define the rest of my life. I walked out of the session into a different world. The clouds sat thicker over my head, but my legs were lighter underneath my body.

I decided to call my mom. “Yeah, she thinks I’m really depressed. Like, really, really depressed. And she wonders why I didn’t ask for help before this. She says she normally doesn’t prescribe medication during a first session, but she could see how much pain I was in, so she just called in a script to CVS. It’s for Effexor. I have this feeling that things might be about to change for real, but I can’t explain or trust it.”

By that point, I didn’t know who I was without my suffering. If some pill took it away, would there be anything left?

James I. Hudson, a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and the director of the Biological Psychiatry Laboratory at McLean Hospital, points out a cultural association between creativity and depression. “It’s the stereotype of the alcohol-addicted singer who is crashing,” he says, “but they’re great on the stage. Well, that’s creative. But is that the kind of creativity that we want to foster?”

His words reminded me of how Hannah’s pre-Zoloft desire to be a writer stemmed partially from her unhappiness. It made me wonder to what extent I had tied together my own tendency to feel deeply, my misery, my capacity to romanticize that pain, and my value as a human.

By the time I walked into my psychiatrist’s office, I’d let my emotions become so overwhelming — out of fear that I’d lose my essence, my self that could write through pain — that I stopped being able to actually process them. No more feelings for you, my body said. It shut down and masked them with anxiety instead. It didn’t matter if I was myself; I was miserable. I wanted desperately to be able to feel again, just not so much that it sent my nervous system into overdrive.

Seven tumultuous weeks after I took my first pill of Effexor, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor — or SNRI — that tackles both depression and anxiety, the medication started kicking in, and I sent my mom a rambling text. “It’s just a lot easier to get out of bed, do normal things, be excited for my day — music feels different, the outside world looks different. I think I had just accepted that life was going to be fundamentally worse now/never go back to normal, but I feel like my real life is starting again & I just woke up from a very long nightmarish dream.”

My journey back to myself had only just begun. But my Effexor offered me a kind of strange bridge through the glass wall between me and my life, an invitation to step back into my body and see if I could bear what I found.

‘A Blunt Instrument’

GRW: Here’s something I never told Kate: The conversation we had in the Currier’s dining hall was only possible because of Vyvanse, a stimulant.

I am diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD. Without stimulant medication, my mind wanders, and I follow it. A ski patroller could be explaining how to climb in the rescue toboggan, I could be beholding a beautiful work of art, or a friend could be divulging a closely guarded secret, and still, my mind will wander. In its “natural” state — one unaffected by Vyvanse, at least — my mind is slippery, and I will only process the first few words of what someone says until, all of a sudden, I find myself lingering in a days-old joke or sorting through what could next keep my mind engaged and present.

The solution? One compound made of 17 carbon, 33 hydrogen, three nitrogen, seven oxygen, and two sulfur atoms. I take 30 milligrams every morning. Over the course of about an hour and a half, it reacts primarily within my bloodstream and transforms into amphetamine, the key active ingredient in Adderall.

Vyvanse is a miracle. It makes my mind sticky, providing an incredible opportunity: to focus. The medication has allowed me to apply myself in my work at Harvard and enabled countless other meaningful experiences. I am grateful for it.

{shortcode-6f80bff962bf15bd150e84dbc1c8157f91940018}

But here’s why I never told Kate: I’m not sure that the person who was sitting across from her in the dining hall was me. Was it cheating? Without Vyvanse, I am not as able to whittle away at the same few concepts for hours. So was my engagement “natural”? Was the conversation and all that followed from it artificial?

Unlike antidepressants, whose effects take weeks to take hold, the lifespan of Vyvanse and other stimulants is hours long. The shape of my mind is fundamentally different in the morning, before I take my medication, and in the afternoon, when its effects have taken full force.

“It’s kind of a blunt instrument in medicine,” Hudson says of stimulant medications. “It doesn't feel quite natural. It's an unnatural balance.”

“We’re not trying to achieve an artificial thing — it is artificial, a little bit — but the ideal thing is to maintain a homeostasis, a biological resetting of the natural rhythm of things,” he says of the intention and effect of stimulant medications. But he emphasizes that stimulants are far from perfect. “They’ve been around since the ’50s. We haven’t improved upon them,” he says, adding his surprise that no better drug has come about since then.

Taking Vyvanse often does feel like a “blunt instrument.” Ironically, one of the main challenges dovetails the primary benefit of Vyvanse: becoming unable to pull my mind from certain thoughts.

Vyvanse might keep my mind stuck in a four-to-five hour conversation that began as nothing more than a “quick lunch.” I barely budge, my mind unable to pull away, even as I know the U.S. Men’s National Team is playing Wales’ in the World Cup and I would otherwise want to go watch, even as I know class is beginning soon. Vyvanse might also stick my mind to anxious thoughts, pushing me to question again and again whether I know an acquaintance’s name, for example.

The medication also leaves me with headaches. Around eight to nine hours after taking Vyvanse — which lasts for as many as 12 to 13 hours — my brain sometimes starts to feel the “blunt instrument” in force. It tightens, stretches, implodes, contorts, warms up, and bursts into flames, often leaving me in desperate search for a bag of ice to hold against my forehead.

The headaches do have a remedy: another pill, Sumatriptan, which took me years of trial and error to discover. I swallow 50 milligrams of it whenever the headache starts, and, almost always, within an hour, a peaceful clarity replaces the sharp tension in my brain. At the very least, it makes the solitary, nasty, and brutish experience of headaches a short one.

But the other side effects — the heightened anxiety, appetite loss, sweating, and trouble I sometimes have falling asleep — have no remedy, and Vyvanse remains a complicated positive in my life.

I was diagnosed with ADHD and dyslexia in sixth grade following years of apparent struggles to keep up with my classmates.

My mom confirmed this memory. “You were working so hard but struggling to finish assignments on time and struggling to perform up to your potential,” she said, adding that she knew “there must be something going on.”

(“You were, and are, obviously a genius,” she also said. Thanks, Mom.)

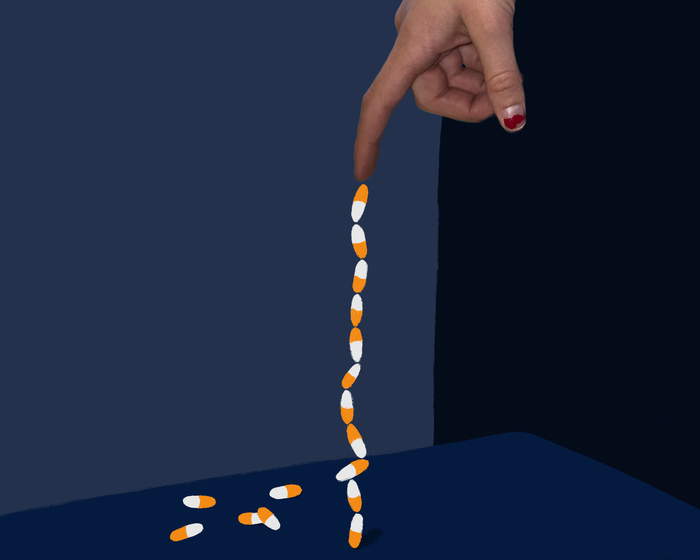

Since my diagnosis, I have tried countless medications before settling — at least for now — on this imperfect combination. Even still, my early morning encounters with the orange-and-white capsule are strange. I stare at it, in awe of its power to shift the very tectonic plates of my world, and I consider. Do I really need my mind to be sticky today, and will I get a headache? Do I have Sumatriptan in my backpack? Is it worth losing access to my “natural” mind, to my “real” self?

Then I toss the pill in the back of my mouth and swallow.

‘To Remain Human’

KSG & GRW: For all its complicated miracles, psychiatric medication works differently — or not at all — for every person. For Alan, the SSRI Prozac provided no respite from either the depression or anxiety for which it was prescribed.

Instead, it made everything worse.

He describes his experience with Prozac as “scary” and “weird.” It transformed him into an entirely different person, he says, one who occupied the same body as his old self but was otherwise removed from it. Joy, pride, and excitement evaporated from activities once filled with them, and he watched life unfold from a distance. He could understand when an event or activity should have brought about an emotion, but he was unable to feel any.

“Everything was just kind of flat. I had no motivation to get out of bed in the morning, and I didn’t want to kill myself,” he says, letting out a dry chuckle, “but I also didn’t want to get up and do stuff.”

Even if the medication muted his depression and anxiety — and even if it kept him alive amid suicidal feelings — Alan was firm: Prozac did not make him better.

“It’s a loss of fundamental humanity,” he says of his experience with the drug, and it left him feeling “more alien and weird and horrible than before.”

Eventually, Alan switched to Zoloft, which was marginally better, and Ativan, a sedative, before resolving to stop using psychiatric medications altogether. He leaned on cognitive behavioral therapy, which he began at the same time as Prozac.

When he left for Cambridge to begin freshman year, he stuffed three months’ worth of Zoloft and Ativan in his suitcase, just in case. And during his first year, the supply stayed there, untouched. He recalls this time fondly. His depression receded, and he was functional.

But as Alan returned to school this fall, tragedies rippled through life at home and in school, and he couldn’t sleep for more than a few hours — often, he couldn’t sleep at all.

He stopped taking care of himself and eventually realized that he was back in the throes of depression. He says he didn’t feel “in control anymore.”Meanwhile, Ativan was still waiting in his suitcase, offering what he thought of as a “tempting lie”: the “promise of a short-term fix.”

In late September, Alan took a pill of Ativan. It was the first time he had used a psychiatric drug since he quit, and he began taking it habitually. The sleep it offered was poor. It would knock him out for nearly 14 hours, but left him extremely groggy during the day.

During winter break, he threw away all his medication and has come to embrace the imperfect reality that life without prescription medication has provided. His depression eased by spring semester, and he now logs about four to five hours of sleep per night.

“Even at my absolute worst worst, I don’t think I ever want to turn off the emotional side of things,” he says. “It’s refreshing to me to remain human.”

‘Humoral Theories’

KSG & GRW: The variety of experiences psychiatric medication creates — highlighted by the disparities between Alan’s, Hannah’s, and our own — points to the enigma central to these drugs. The experts we talked to about this all agreed on one point: how little we know about psychiatric medicine.

Arthur M. Kleinman, a professor of medical anthropology and psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, says that almost all the biological theories that have been formulated to explain mental illness “are going to look, in the future, like humoral theories from the middle ages.” Humorism, a theory that the human body was composed of four “‘humors”’ — black bile, phlegm, blood, and yellow bile — was adopted in Ancient Greece and remained the primary Western medical consensus until the 19th century.

Many researchers have nonetheless tried to elucidate the causes of anxiety and depression.“Do we have any biological models of this that are true?” Kleinman asks about the theories that have emerged. “No. Do psychiatrists tell people that they have a biological disorder? Yes. Is that an exaggeration or a misstatement? I leave it up to you.”

Diego A. Pizzagalli, professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and director of the Center for Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Research at McLean Hospital, explains that many in the field conceptualize depression broadly using a “biopsychosocial model,” taking into account risk factors stemming from brain, mind, and society.

Psychiatric drugs like SSRIs and SNRIs — which have slightly higher efficacy rates than placebos — are prescribed nowadays to address the biological component of the biopsychosocial model, at least in part.

Clinicians began to treat psychiatric disorders with SSRIs and SNRIs when scientists thought chemical imbalances caused these disorders, a theory that has since been proved inadequate. The idea first originated from decades-old research on rabbits and mice, according to Anne Harrington, a History of Science professor. In the 1950s, researchers fed the animals reserpine, which slowed their nervous systems, before giving them antidepressants, which brought back some of their activity.

The researchers discovered that the reserpine lowered levels of norepinephrine and serotonin and that antidepressants raised them. This study, among others, contributed to the development of the chemical imbalance theory.

“What’s become more and more clear is that probably, the original animal model was a pretty poor analog to human depression,” Harrington says.

Pizzagalli explains one problem with the theory that low serotonin levels cause depression: While serotonin levels increase within hours of taking an SSRI, it takes weeks for patients to feel an improvement.

“Maybe depression is not only associated with a low level of serotonin, but there are other abnormalities, other dysregulations in different neurochemical pathways,” he says.

Similar patchwork understandings exist for other medications and disorders, like the use of Adderall for ADHD. For people with the condition, “it is somehow able to focus the brain by ways we don't know,” says Hudson. “When it works, it can work very well.”

“The introduction of drugs changed the game,” Harrington concludes, “but it didn't necessarily translate into new biological understanding as to why people get depressed and exactly how these drugs work.” The gaps in knowledge have made it difficult to develop better drugs and treatments.

Correspondingly, mental health diagnostic practices must rely on solely recognizing symptoms of a particular mental illness.

Caleb P. Gardner, a psychiatrist at Cambridge Health Alliance, explains how this runs counter to diagnostic practices for most physical illnesses. Take strep throat, for example. Sore throat, headache, and fever are symptoms of the illness, while bacteria in the throat and tonsils are its root cause. Tylenol and salt-water gargling are ways to relieve symptoms, while antibiotics attack the cause. “Lots of medications are powerful for symptoms” of mental illness, Gardner says. “But they don’t get to the bottom of what’s going on.”

This lack of clarity has leaked into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Published by the American Psychiatric Association, the DSM outlines the symptoms and diagnostic criteria for every recognized mental disorder.

According to Gardner, the DSM facilitates a “cookbook approach” in the modern delivery of psychiatric services. People report symptoms, he says, and then their presentation gets matched with a DSM diagnosis, indicating which medications they should try first. “That just isn’t adequate to addressing what’s going on for people,” he says. “And it can lead to lots of things getting overlooked.”

‘Popping A Benzo in the Train Car Bathroom’

KSG: I spent the entirety of the first Sunday of last May in my bed, rain falling outside, humidity lacing my room. I’d tried everything — putting my legs up the wall to return blood to my heart; inhaling for four, holding for four, exhaling for four, repeating; meditatively praying to some secular god of mental illness that the terrible spiky panic-inducing feeling inside of me would ease up just a bit. I was clenching my teeth so hard that my whole mouth tasted of blood.

When I arrived at my psychiatrist’s house two days later, I knew she could tell something was wrong. I sat in my usual chair but with my shoes off and my legs in an asymmetrical twist underneath me, my arms wrapped around my waist. “So, I haven’t been doing so great.” I swallowed. “I couldn’t leave bed on Sunday. My chest, it’s still hurting right now.” I pushed into my breastbone hard. “I’m trapped, right inside here. I don’t know what’s wrong with me.”

She asked me why I hadn’t called her. “This is what I’m here for,” she said, her voice a mixture of desperation and frustration. “You’ve been dysfunctional. We’ve talked about this. When you can’t function, it doesn’t mean you’re failing. It means you need to ask me for help.”

She wrote up a script there and then for Ativan, a short-acting benzodiazepine. I’d done my research; I knew Ativan wasn’t like Effexor. Ativan would gradually become less effective the longer I took it, meaning I could develop tolerance.

But it was either take the drug, my psychiatrist told me, or go to the emergency room. I could not continue on as I was.

“Yesterday, the Ativan was amazing and I barely felt any anxiety all day,” I emailed my psychiatrist a few days later.“When I woke up this morning — more than 6 hours since my last dose — the anxiety was back in full force. I think I’m just feeling nervous/scared that the Ativan helps me so much; I know it’s a short-term solution,” I wrote, “but I am still feeling overwhelmed. I kind of hate the idea that I’m reliant on pills to not have a super high heart rate/chest pain, even though that might just be what it is for now. Anyway, just wanted to share!”

She reassured me that in her 30 years of practice,“no patient I have treated has ever become ‘addicted’ to any benzodiazepine.” Her patented sarcasm leaked through the screen. We’d spend time unpacking my paranoia, she said, in our next session.

My anxiety is hard to characterize. It feels as though someone has halved my lungs, poured sand down the space in my chest where breath comes in and out, turned up the dial on every one of my sensory neurons, and ordered particular muscles to contract to the point of pain. Yet it is, by definition, a psychological, not a physical, disorder. Right?

I have never once taken a pill of Ativan without feeling guilt. I know, in theory, that I’m allowed to alleviate my own suffering. But somehow, it feels different from my antidepressants; the short-acting nature of the drug makes me hyperaware of how directly it acts on my nervous system, sending a blanket of calm through my muscles until I am released into myself again. It feels like cheating to ease this paralyzing irrational tightness in my chest with medicine. It also feels like magic — which, of course, makes the whole thing even scarier. Can pills really work this easily, this well, this fast?

{shortcode-4c85e8c70b3f96bd2ac399a9c39dbf74e09bbda1}

When I’d first heard the word “benzo” come out of my psychiatrist’s mouth, I’d imagined a mess of a middle-aged woman popping pills whenever the most minute stressor came up, pathetically incapable of facing her life head-on. It was a misogynistic and derogatory cultural narrative, and I fought against it as I tried to reconcile with the pills’ presence in my life.

I have developed a bit of a tolerance, though not nearly as much as I once feared. I’m prone to black out after one glass of alcohol, or fall asleep at 6 p.m., if I have taken the drug in the afternoon. On the not-infrequent days the Ativan doesn’t work perfectly, my anxiety dripping through the medication like a leaking faucet, my fear skyrockets.

This summer, my best friend started a highlight reel in her Snapchat memories featuring me and my chalky pills, captioned: “Kate popping a benzo in the train car bathroom. Kate popping a benzo in the art museum. Kate popping a benzo waiting for the traffic light.” I looked at the pictures recently and was caught off-guard by how joyful I looked. It seems I had integrated this despised magical aid into my life.

As of now, I take two milligrams of Ativan every morning — my chest pain is consistently the worst just after I wake — and sometimes throughout the day, meaning I am intimately familiar with my Ativan-induced guilt. But I’ve made some peace with it. I understand a little better now that it is just a relic of my outdated notion that I can beat my anxiety by sheer force of will.

I have faith that a time will come when I won’t need these chalky white pills anymore (and, to be honest, I can’t fucking wait). But that time isn’t now. I’m not cheating at life when I pop a benzo. I am trying my damn hardest to live my life the best that I can.

‘Good, Valuable, Lovable, Worthwhile, Important, Deserving, and Strong’

GRW: My junior year of high school, the anxiety that sometimes emerged from stimulant medications left me flirting with antidepressants.

I was prescribed the SNRI Cymbalta, and the experience still haunts me. I had no fears, no anxieties. I rarely experienced sadness, and I did not feel like myself.

I chronicled it all — the anxiety and the mind-altering medication — in a personal narrative for my AP English Language and Composition class dated January 2019. I addressed the reader directly, asking sarcastically what they would do if they were me, if “you lost control of your mind.”

The narrative takes “you” through the feeling of acute anxiety and panic attacks before “you” end up at the psychiatrist’s office. “He says he has this pill he doesn’t usually give to teens but he’ll give it to you,” I wrote.

Weeks later, “you can’t control your mind.” Each day feels unnervingly calm. “It feels sorta like gliding,” I wrote. “What would you do? (I ask, of course, because I don’t know what to do.)” I stopped taking Cymbalta after my junior year.

Reading the narrative now reminds me of how much I struggled and attests to how much I have grown since. My growth is a testament to my great therapist. His powerful form of cognitive behavioral therapy has given me the tools to reconstruct my mind and the course of my thoughts. To a great extent, I have overcome the anxiety and panic that cast a shadow over my adolescence.

“Everyone’s core self is GVLWIDS,” my therapist has told me countless times: “good, valuable, lovable, worthwhile, important, deserving, and strong.” I’ve been his patient for nearly a decade, and I am learning to embrace this truth more and more.

Thoughts drive feelings, feelings drive behaviors, behaviors drive thoughts, and the cycle continues. Negative thoughts, feelings, and behaviors: these often emerge from a poor self-perception, the part of me that has not yet realized that I am GVLWIDS. The good thoughts, feelings, and behaviors? Those come from my good self-perception, which has blossomed.

Harrington tells us about a study that compared the efficacy of tricyclic antidepressants, a predecessor of SSRIs and SNRIs, with cognitive behavioral therapy. “And cognitive behavioral therapy won,” she says. “And not only that, the rates of relapse were significantly lower.” I’m not surprised.

Yet I sometimes feel as if my anxiety can prove to be more powerful than the tools that CBT has provided, which is a reality I have learned to embrace as part of my life. My experience with Cymbalta still looms over me, but my distrust of antidepressants is receding. I am recognizing how different my experience could have been, and I am coming to understand the role medication can play alongside therapy.

‘Oh, Well, Fuck It’

KSG & GRW: Rebecca’s ambiguous experience with medication has forced her to contend with what it means to summon a pragmatic faith in science, her providers, and a better world.

Her problems with mental health — including depression, anxiety, and ADHD, her current diagnoses — began in middle school, she says.

But her parents were never particularly enthusiastic about the prospect of her taking psychiatric drugs.

After trying therapy for years, she got to a point where she asked herself: “Is this really all? Is this as good as it’s going to get? Because it still isn’t awesome.” Cynicism laces her words.

Starting medication was a fairly simple decision for Rebecca. “Do I feel shitty most of the time, or do I not feel shitty most of the time?” she says, explaining the choice she faced. She wasn’t worried about losing who she was. To her, medication was about mood and motivation — nothing more, nothing less.

The process of getting on meds was rocky. The antidepressant Wellbutrin came first and immediately made her more sensitive to caffeine; she stopped drinking coffee and energy drinks. With the next medication she tried, Zoloft, came nausea; she took it at night so she could eat during the day. She did, however, notice that “it was easier to get up and start doing stuff.”

During reading week last semester, after a combination of messed-up finals period sleep schedules and forgetting to order a prescription, Rebecca stopped taking nearly all of her meds. The striking part? “I felt no different,” she says. “There was nothing.”

We asked her why she continues taking the meds. “Oh, well, fuck it. I might as well,” she says. “A doctor gave me these, she probably had a rationale. I trust her.” The faith Rebecca has is less in her medicine than in her psychiatrist and in some sort of scientific method that she knows, or perhaps hopes, is leading her in the right direction.

When Rebecca started her medications, her psychiatrist told her they would raise the floor of how terrible she felt. They haven’t done that, she says, but she recovers more rapidly from bad episodes. Though she’s not sure if that’s because of the drugs, or the passing of time, or therapy, she asks: “As long as I feel better, does it actually matter?”

“The process of getting diagnosed with something has been mysterious,” she says. “I’m not really sure what I have.” She suspects a disparity between what she’s been diagnosed with formally and what her medications treat “versus what’s actually there.” She’s hoping some clarity will emerge with time.

She recognizes, perhaps even embraces, the blind spots of her medication and the messy ways in which it works. She describes a gradual process of “making peace” with the fact that her medication won’t treat the core issues.

But unlike us, Rebecca is actively trying to care less about the mechanisms behind her pills. She rejects the idea that her meds could lead to a full recovery; she says that notion “implies a finish line that there just kind of isn’t” when it comes to healing from mental illness.

‘The Normal Human Animal’

KSG & GRW: Despite flaws in the current models used to diagnose and treat psychiatric disorders, experts gesture towards a different future, one that might require a radical overhaul of how disorder is conceptualized in psychiatry and offer doctors and patients better routes towards easing suffering.

Some researchers are intrigued by how psychiatric disorders often overlap in patients’ presentations and theorize that a better understanding of their roots could stem from studying the intersection. This might be why the same medications work to treat disparate conditions, Hudson thinks. He doesn’t find it particularly plausible that SSRIs and SNRIs that are often prescribed for anxiety, depression, or obsessive-compulsive disorder “would all somehow magically work in each of these conditions,” he says. “It seems more likely that somehow there were some commonalities, some common biological abnormality that might underlie a spectrum of conditions.”

Rebecca’s case — having a diagnosis on paper that she doesn’t feel aligns with her actual experiences — fits into this alternative conceptualization.

Others, like Gardner, believe that seeing patients for their individualities rather than for their diagnoses can be an avenue towards understanding underlying causes of psychiatric disorder and how medications can act on them. “To say whether or not a medication is helpful, or harmful, or productive, or regressive has to do with the individual person and their individual circumstances,” he says. To make personal treatment plans, psychiatrists need a “full picture of what's going on psychologically.”

Key to centralizing patients in their care, Kleinman says, is bringing humanity back to psychiatry.“Something deeply important in caregiving,” he says, “has been lost, is being lost.” He suggests that interpersonal care might be a reason the placebo effect has always been particularly high in psychiatry: the trust in the doctor-patient relationship “has a big effect on psychiatric outcomes.”

Despite the mild effect of her medication, Rebecca speaks highly of the close relationship between her therapist and psychiatrist. It’s nice “to have an integrated care team,” she says, “as opposed to just two separate doctors.” Her trust in her providers is, according to Kleinman’s line of reasoning, integral to the positive aspects of her experience.

The core issue is that psychiatry hasn’t defined the underlying systemic dysfunction causing mental illness, Hudson says — leaving the field with incomplete treatments. But in his mind, “even though we don’t know exactly what the abnormality is, what we’re trying to [restore] is normality — a true normality and a true homeostasis.”

“It's my fundamental belief that there is a normal self that does exist” beneath dysregulation, he says, “that normal, homeostatic self. The normal human animal.”

A Tapestry of Resilience

KSG & GRW: In some ways, our journey ends exactly where it began: we are struggling to capture in words the enigma of psychiatric drugs.

Our investigation has elucidated few real answers. The clarity we desire clashes with the very nature of pain, its randomness and its inexplicability.

How can we conclude? How do we write something that represents the humanity of those living with mental illness amidst such terrifying uncertainty?

But our friendship, once engulfed by the questions that emerged from that late -November conversation in the Currier dining hall, has finally returned to its equilibrium: ordering McDonalds M&M McFlurries at 2 a.m., and going at least a week without an all-consuming conversation about mental illness.

And we did uncover something, after all.

There is one kind of resilience we get to choose: the kind that comes from making the decision to grit our teeth and push through, to go above and beyond even and especially when we’re struggling.

And then there’s the other kind of resilience we don’t get to choose. It shouldn’t be glamorized. It feels like the hundredth minute treading water, and it often looks as inconspicuous as getting out of bed while panic spins around your head, or maintaining a conversation through a splitting headache. It is also a profoundly daring act.

Let this be a testament to every kind of resilience that the pill-taking among us display. Threaded together by some unknown hand into a messy, colorful tapestry, it absorbs the impact when we crash — over and over again — onto hard ground.

***

If you or someone you know needs help at Harvard, contact Counseling and Mental Health Service at (617) 495-2042 or the Harvard University Police Department at (617) 495-1212. Several peer counseling groups offer confidential peer conversations. Learn more here.

You can contact a University Chaplain to speak one-on-one at chaplains@harvard.edu or here. You can call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or text HOME to the Crisis Text Line at 741741.

— Staff Writer Kate S. Griem can be reached at kate.griem@thecrimson.com.

— Associate Magazine Editor Graham R. Weber can be reached at graham.weber@thecrimson.com.