{shortcode-82b0ae355cc04b442dbf062f651b6f40cba41035}

{shortcode-9cb9f65186531bc40ac65bf97e3ffda3f8ab61f3}pon entering his home on April 8, 1969, then-University President Nathan M. Pusey ’28 found a list of demands tacked onto his door — a call to abolish Harvard’s ties to the ROTC and stop the University’s expansion into working-class neighborhoods. Pinned up by members of the Students for a Democratic Society, a radical group of anti-war Harvard students, this sheet of paper served as a mere hint of what was about to unfold in the next eight days.

The following morning, SDS members and others were eager to put their words into action. The crowd chanted “Fight! Fight!” and then, more than 100 strong, occupied University Hall.

They ejected all administration officials and staff members — an image of one dean being carried out of the building made the front page of nearly every national newspaper. A few hours later, the demonstrators chained the doors to the building shut. The building was now theirs.

Throughout the day, the student protesters voted among themselves, agreeing not to destroy file cabinets, to solely permit reporters from The Crimson and Harvard Radio Broadcasting to stay, and to offer nonviolent resistance if police were called to clear the building.

Joining SDS in this occupation were some members of the Association of African and African-American Students, or AFRO. They were advocating for another demand: the departmentalization of Afro-American studies.

Though, for Black students, this demand was always first.

“I think a lot of Black students needed Afro-American Studies to make Harvard feel like home,” Lee A. Daniels ’71, a former Crimson writer, says. “A lot of students didn't have that kind of safety veil, and a safety veil was needed because the late 1960s were very contentious.”

Black students first called for the creation of an Afro-American Studies Department a year earlier, in 1968. But the ensuing discussions were unsatisfactory, in part because they disregarded one of Black students’ core principles — that the new department have its own autonomy. AFRO was growing restless.

150 Cambridge police officers assembled at the Fire Station on Quincy Street later that afternoon. The next day, at Pusey’s request, armed with riot shields, billy clubs, and mace, police stormed into the building with a vengeance.

“The police, in a sense, had been waiting for a long time to hit some Harvard kids upside the head,” Ernest J. Wilson III ’70 says.

The protests and demands didn’t come in a political vacuum. The highly -charged political atmosphere of the late 1960s — inflamed by the Vietnam War, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy ’48, the Chicago riots, and the ascent of Richard Nixon — gripped the campus.

Martha Biondi, a professor of African and African American studies and history at Northwestern, says calls for Black studies were resounding across higher education at the time.

“Students were very disenchanted with the slow pace of change, and this really hit home after the assassination of Martin Luther King and April of 1968,” says Biondi, a visiting scholar at Harvard. “I think students all over the United States at that point really stepped up and accelerated leadership of the Black liberation movement.”

Biondi’s 2012 book, “The Black Revolution on Campus,” chronicles this period of time where calls for Black studies sprung up like wildfires. She draws a straight line from students protesting on campuses like Harvard’s to the Black freedom struggle and the gains it won for Black people in America.

Now, as the leaves change, agitation is in the Cambridge air again. AFRO, for one, has been reborn: Prince A. Williams ‘25 issued earlier this month “A Call for Black Organization” under “The New Afro,” almost 55 years after the African and African American Studies Department was created because of AFRO’s advocacy.

Like in 1969, AFRO’s charge doesn’t happen in a vacuum: from the emergence of Black Lives Matter to protests about unionization, sexual harassment, fossil fuel divestment, and war in the Middle East, students have taken, again and again, to Harvard Yard, all with one goal: to get one of the world’s most influential institutions to effect the change they believe it can.

What does the campaign to found Black studies have to teach all people discontented with the university, society, and world they find themselves in? And is there some other lesson in the story of Black studies after its creation, some lesson about what it takes not just to begin a movement but to sustain the fruits of it?

‘Left Our Blackness at the Entrance’

{shortcode-dd08abb0bb2b02bf4881baaa9fb305566107f8d4}he Black experience at Harvard in the 1960s was one of isolation.

The class of ’69 numbered 1,500; 36 of them were Black. Daniels, the former Crimson writer, says he made it a point to “know every Black student at Harvard, know their names, have spoken to them.”

But an awareness of fellow Black peers did not imply a sense of belonging. Each student knew they were “a stranger in this strange land” as Lee S. Smith ’69, the managing editor of his class’s Harvard Yearbook, puts it.

The experience of Black students, Smith says, “was the same in that it wasn’t the white experience.”

Of those 36 students, six were women. In the ’60s, those six women were students of Radcliffe College, which had merged with Harvard in 1963, allowing Radcliffe students to take classes at Harvard.

Consider Harvard through the eyes of young Muriel Morisey ’69. In 1969, she contributed an essay to “Blacks at Harvard,” a section of the 333rd issue of the Harvard Yearbook.

“Mine is particularly about being a Black woman,” she tells us now. “It’s pretty dark,” she lets the thought hang, struggling to believe that it was written by her. “I think it’s called ‘A Feminine Hell.’ That’s the name!”

“Radcliffe does not yet understand her black students, and Harvard does not yet know what to do with its women, and as a result the black Cliffie does not yet know what to do with herself,” Morisey wrote in that essay.

Morisey remembers being “only one or one of two women” members on the executive committee of AFRO. Her other involvements included the choir. “There was no such thing as a Black student choir,” she says, lamenting that the Kumba Singers did not yet exist. In her time at Radcliffe she realized that if “you’re gonna sing, you’re gonna sing with a whole lot of white people.”

And yet, Morisey was to some degree immune to this sense of alienation; she had already been acquainted with Harvard, familially. She pauses at one point to ask, “Have you heard of the writer Ralph Ellison?”

“Well, Ralph Ellison and my dad were first cousins,” she says. “Ralph and I had a very strong relationship after my father's death.”

“Ralph” would, to a degree, guide her experience, but Morisey and Harvard were a fine match in and of themselves. “I have to tell you, I was ready. I came out of one of the finest Quaker Schools in Philadelphia,” she says. “I arrived at the Harvard campus academically ready. ”

Hers is a familiar tale. For Smith, looking at himself from the outside in has granted a certain self-consciousness. “Getting into Harvard, having gone to a prestigious prep school for a year, my transition into that sort of intense, heady intellectual atmosphere of the East Coast was a little smoother than some people,” he says.

At first, this pattern seems an eerie coincidence, perhaps a troubling correlation, but it is ultimately a phenomenon explained by the thinking in African-American socioeconomics at the time.

“Not just at Harvard, but nationally, that cohort of Black students who came out of high school in ’65, who spread out to these colleges in numbers that were unprecedented, viewed themselves, rightfully, as a new form of leadership of the Black community,” Smith says. “We weren’t just there to get an education. We didn’t talk about it this way, but I think we had a different sense of our larger obligation to our race.”

“The Negro race, like all races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men,” Du Bois declared in his now notorious essay, “The Talented Tenth.”

“It is the problem of developing the Best of this race that they may guide the Mass away from the contamination and death of the Worst,” he wrote. The fate of Black people, Du Bois pronounced, would rest in the hands of “the college-bred Negro.”

And now it was happening; “the Best of this race” was busing into the nation’s finest school in increasing numbers. Was this Du Bois’ vision of emancipation finally coming to fruition?

Not quite — not all the Black students at Harvard were coming from these elite high schools.

“My boyfriend and his friends had a very isolated, very unhappy experience at Harvard,” Morisey tells us. “Harvard had not figured out that if you bring a Black kid from the worst neighborhoods of St. Louis, Nashville, Los Angeles, and you just bring them into Cambridge and you enroll them at Harvard, that doesn’t mean it’s going to go well for them. It doesn’t mean they’ll feel comfortable or welcome. And they didn’t.”

Morisey recalls one of her boyfriend’s friends. “Nobody had a plan at all for how he was going to cope at Harvard,” she says. As far as she remembers, he never graduated from Harvard.

“I feel as though he was Harvard’s big failure,” she says. “He was smart and funny and had wonderful musical ability.”

“Somebody should have helped him feel better about his experience.”

All of this occurred under the guise that Black students at Harvard at the time were an embodiment of integration at its best.

“The community did not exist. We had to come to Harvard and Radcliffe to be men and women — not white or Black — just individuals in search of individual fulfillment. That was the promise which integration held out for us,” wrote Wesley E. Profit ’69 about the Harvard of 1965. “We were first and foremost reporters for the Crimson, photographers for the Radcliffe News Office, volunteers at PBH, and members of the Young Dems. Little else mattered for the jobs we were doing. This was integration. We were finally going to get the chance to have experiences previously denied us because of our color.”

He continued, “Consequently we left our Blackness at the entrance to the various organizations we joined. It was irrelevant. We only happened to be Black at whatever we happened to be doing.”

However, the veil of a post-racial Harvard was soon lifted. The introduction of more radical Black activists like Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael, who later went by Kwame Ture, gave rise to a new militancy of Black people, alongside a heightened expression of Black pride and self-determination.

In the face of this racial and political turmoil came the need for a sense of security, a means of understanding oneself and each other. Their yearning found an object: a department centering Black history and experience.

“I think none of us wanted the experience of the people who followed us to be as isolating,” Smith says.

Harvard’s Black population grew each year, with the number of Black students almost doubling between 1968 and 1969. Black Harvard now had the manpower for mobilization.

“In many cases,” wrote Charles J. Hamilton Jr. ’69 in an October 1967 Crimson Supplement, “blacks are leaving behind their token presence in other undergraduate organizations for the sense of unity and expression found in an all-Black organization.”

{shortcode-939fe1443e71aa3862535ff80ad9974947c881ea}

‘To Fair Harvard’

{shortcode-21cc3534b02e5a90dd1b6e61be0fe28423896a7e}s momentum was building within these all-Black student spaces, on April 4, 1968, MLK was assassinated.

Six days after his assassination, Harvard organized a service at Memorial Church. A congregation of 1,200 mourners gathered. Less than a dozen of them were Black. Instead, nearly 80 Black students gathered outside the church to hear Jeffrey P. Howard ’69, head of AFRO, deliver a message:

“We seek a place for Black people within the Harvard community.”

Black students would soon spell out their vision for their place on Harvard’s campus. In the next morning’s issue of The Crimson, AFRO issued an advertisement. Taking up half a page, in font nearly an inch tall, AFRO writes: “To Fair Harvard”

“Do you mourn Martin Luther King? Harvard can do this.” This was followed by four requests and a description of Black Harvard’s grievances:

- Establish an endowed chair for a Black Professor

- Establish courses relevant to Blacks at Harvard

- Establish more lower-level Black Faculty members

- Admit a number of Black students proportional to our percentage of the population as a whole.

Four days later, on April 14, the Ad Hoc Committee of Black Students was formed to advocate for these demands. On May 9, Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Franklin L. Ford created the Faculty Committee on African and Afro-American Studies, also known as the Rosovsky Committee. Chaired by Economics professor Henry Rosovsky, the Rosovsky Committee consulted with Black students on campus about creating a program on the Black experience.

Ford initially tasked the Rosovsky Committee with “investigating the place” of Afro-American studies in the Harvard curriculum. But the students involved had more concrete ambitions.

“A group of us began to meet and say: ‘What should we do at Harvard?’ And so one of the things that we did was to begin to look around the country,” Wilson, a member of the ad hoc committee, recalls. After extensive research, they put together a list of the leading scholars in African-American studies, with the hopes of creating their own department on campus.

Having grown up on Howard University’s campus — a historically Black university in Washington — Wilson was no stranger to Black Power movements. Just a year before coming to Harvard, Wilson’s cousin caused a “ruckus” on Howard's campus after wearing an afro hairstyle to accept her title of homecoming queen.

Moving from being surrounded by Black political thinkers to a predominantly white space like Harvard inspired Wilson to begin political organizing, leading to his participation in the ad hoc committee.

In the end, the Rosovsky Report, published on Jan. 20, 1969, included recommendations calling for a program, not a department. The report also called for a Black cultural center and the hiring of more Black studies faculty — but did not include a clause for student participation in selecting those faculty members, terms that many students had pushed for.

“Much to our disappointment, however, the communique finally issued by the Standing Committee on Afro-American Studies proved Harvard’s response to be inadequate and superficial,” Howard wrote. “There were no provisions for student participation, for innovation in academic approach.”

Meetings and Meat Cleavers

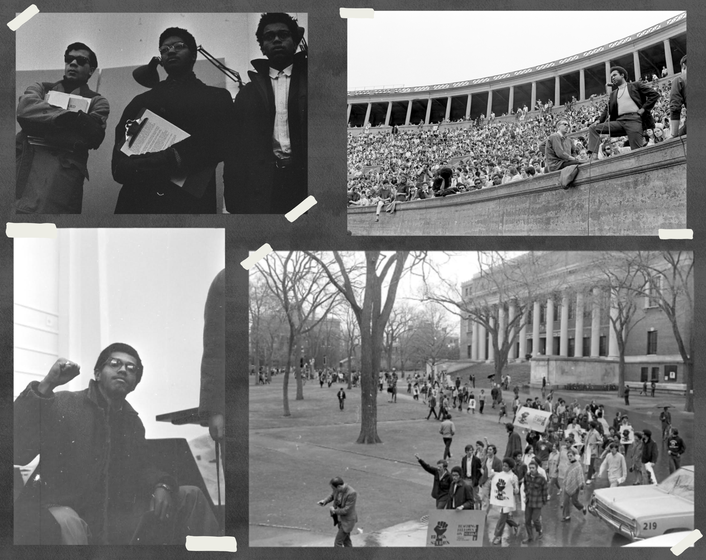

{shortcode-69a9ed06c887cb075e6988b5c6d61980cc21c96c}eeting minutes, written testimonies, and contemporary news reports all tell the story of Black studies’ founding. The photographs taken by Smith, the Harvard Yearbook editor, show it. At all of the important protests at Harvard — whether it was Mallinckrodt Hall, University Hall, or Harvard Stadium – Smith was there, shooting photos for the yearbook. He would end up taking thousands of photos, most of which he still has today.

Smith grew up in Dallas, in the segregated South. He was the first Black student to attend the prestigious St. Mark’s School in Texas. “I integrated the school,” he said. From there, Smith would go on to Harvard, where he was one of the 36 Black students in his year. In his first year, he integrated Wigglesworth G-21, where he had three white roommates.

But he didn’t spend most of his days in “Wigg.” Instead, he spent time at the yearbook offices, then on Dunster Street, which he remembers as a meeting place, a sanctuary, even. But still, “I was the only Black student there.”

Editing the yearbook and photographing for it, Smith knew his own limits. The more he photographed, the more he gained an appreciation for “the power of the pen.” His senior year, he invited eight of his Black friends to write articles in the yearbook about their experiences on Harvard’s campuses. “Look, you have editorial license,” he told his peers. “Just sit down and think about it, from any perspective. But give us a window into being Black at Harvard.”

When Howard put pen to paper in ’69, he called his essay “No More Tea Anymore.” Howard explained that for months — since AFRO had first put their demand in The Crimson — the cycle had been the same. National news, escalations in Vietnam, and an ongoing labor movement all served as fuel to restart the fire — Black Studies Now! — and each time, that fire was put out cordially. Administrators and professors sought to extinguish it with tea and cookies laid out across a breakfast table: the Rosovsky Committee.

As Howard writes it, he and his peers began to see through the ruse.

“If a tradition, a rule, or a channel does not facilitate, rather than hamper a fast resolution of a conflict, allowing each side maximum expression of its position, and the opportunity to understand the other’s, then that tradition, rule, or channel is illegitimate and should be abandoned,” Howard wrote. “We are willing, if necessary, to force this recognition upon the Harvard Establishment.”

And force they did. The first front line was University Hall, where Black students demanded Black studies in addition to those calls tacked to Pusey’s door.

{shortcode-5dcd5903223bee5ee0d1c1c1ec52e8e39d6ed008}

On April 10, students called for a shutdown of the University itself, by means of a three-day student strike. AFRO spelled its demands out explicitly this time, officially adding Black Studies to the other demands. On April 14, a crowd of 10,000 gathered at Harvard Stadium and voted to extend the strike by another three days.

Then, in Howard’s words, the university “acquiesced:” the “special privileges” ROTC once had were done away with. This was enough for the organizations to call off the strike, but the University’s expansion was not addressed. Tensions lingered, as the Faculty also put the matter of Black studies on hold.

Eventually, after extensive pressing by members of AFRO, faculty members agreed to meet for “office hours.” After hearing the students’ demands again, the faculty decided to meet and discuss whether to create a Black studies department at the Loeb Drama Center — a fitting stage for the drama that would ensue, Wilson says.

The stakes of that meeting were high, so much so that outside one student waited with a concealed meat cleaver in hand. “Needless to say, that got everybody’s attention,” Wilson says.

{shortcode-1d0b241f0d9a0ccd3e4643ad55cafde65a1ec414}

It came down to a vote, thumbs up or thumbs down — would Black studies be a track contained within other social science disciplines, as the faculty seemed to want, or a department in and of itself, as the students wished?

Ultimately, the faculty voted for the creation of an Afro-American Studies Department, 251 to 158, but a demand fell to the wayside: student input on faculty appointments in the department.

A triumph though it was, to some students, the win felt hollow. “Harvard accepted Afro-American studies, not because it wanted to, but because it had to,” writes Howard, explaining that there were two reasons why the administration acquiesced to their demands. “First, they would avoid a messy confrontation, compounded by the fact of our Blackness and the validity of our position,” Howard continues. “Second, by dangling a department over our heads, they could persuade us to not risk losing it by demanding any fundamental structural changes.”

To Howard, this was a disgrace: “Only when students are projected into every stage of the decision-making process can we be assured that our interest will be protected.”

‘Wow!’

{shortcode-dd08abb0bb2b02bf4881baaa9fb305566107f8d4}o Smith, the story of Black studies’ founding was less one of heroism than of a kind of martyrdom. “We graduated in ’69 and of course, it’s the next year when the Department was sponsored — we were gone,” he says. “We were the impetus or stimulus or motivation for its creation, but we didn’t get to participate or reap any of the benefits.”

But what those benefits would be was not yet clear. “Each step doesn’t tell you what the next step looks like. Each one’s organic,” he says.

In the first semester of the Department, students felt that course offerings fell short of even the lowest expectations. “For our hard work we got a swift kick in the face, an insult to our individual intellects and to our racial heritage,” Howard writes in his yearbook essay. “Imagine this stupendous feat. The history and culture of Black America during 400 years of slavery and quasi-freedom, the remarkable story of our survival in the face of systematic oppression, summed up in two half courses requiring three hours a week for one academic year. Wow!”

But Howard and others wouldn’t be around to push for better. Harvard “waited for the student activists to pass on and then there’s a period of stasis,” Biondi says. “They weren’t initially very robust and thriving.” Biondi explains that in the ’70s and ’80s, the Department struggled to raise funds and hire scholars.

“There was a lot of pushback and a lot of initial disappointment,” Biondi says.

Wilson agrees that the delay of the Department’s development was two-fold. One problem was that the Department didn’t have very much money to fund faculty, research, and space. The other problem was that the department struggled to find and retain faculty members.

It was hard to recruit top-tier faculty in part because professors with tenured positions at other universities were not willing to move to Harvard’s department, especially because it was not well developed. Visiting professors would come for a few years, but would leave before they could help build a cohesive identity for the department.

“It really didn’t have to work out that way,” Wilson stresses. “The big turning point was when they finally said: ‘Well, we really have to do something here, and it’s not working under the current leadership.’”

“And they brought in Skip.”

‘Black Studies’ New Star’

{shortcode-8c0dd475ea3269f67b1a4d37d27db5cc232a1fc2}ilson wasn’t the first one to mention Skip to us.

“Skip wasn’t there,” Daniels says, disappointed, about his last visit to the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research.

Dell Hamilton, the interim director at the Hutchins Center, tells us about “Skip’s multi-pronged set of skills.”

“Skip, he was just unbelievable,” Charles Hamilton remarked. “In some ways, if we didn't have a Skip Gates, we probably would have had to make him up.”

They were talking, of course, about Henry Louis Gates Jr, who, on his arrival at Harvard in 1991, was crowned “Black Studies’ New Star” on the front page of The New York Times Magazine.

Gates didn’t always have academic ambitions, though. When he was an undergraduate at Yale, he carried that oldest of parental ambitions with him: becoming a doctor.

But the gothic New Haven buildings had their own haunting presence. Bobby Seale, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, was on trial, “just a couple blocks from campus,” Gates remembers. Seale was suspected in the murder of Black Panther member Alex Rackley. “We felt that the charges were trumped up,” Gates says.

The Black Panthers sprang into action, and the young Gates was one of many intent on bringing their college town to a halt. “It was called a moratorium because no one wanted to call it a strike,” he inserts. “But it was a strike.” This culminated with the historic May Day rally on the New Haven Green in 1970.

Other protests would follow, in what was, for Gates and for Harvard, a tumultuous year. Vietnam, labor strikes, a general climate of unrest – the Henry Louis Gates Jr. who would become the chair and patron saint of Afro-American Studies’ was molded by the same collision of forces as the Department itself.

After graduating from Yale, Gates went to Cambridge to complete his English Ph.D., where his literary friends Kwame Anthony Appiah and Wole Soyinka broke the news to him: he wasn’t going to be a doctor. Instead, they told him, he was destined to teach Black studies.

When Gates arrived at Harvard, headhunted from Duke, he found that there was only one professor tenured under Afro-American Studies: Werner M. Sollors. Gates’s predecessor, who he described as “the great historian Nathan Huggins,” had recently died. Neil L. Rudenstine, who had been named University President, offered Gates the position of chair with a charge: build the greatest department of African American studies in the world.

“And the rest, as they say, is history,” says Gates, 30 years later.

That history was a long time in the making. Gates attributes it to the fact that Sollors and Huggins had “just had not been successful in recruiting other scholars as brilliant as they.” Fine, Rudenstine said. He asked Gates to draw up a list of the people he would like to see hired. “I was like, wow, a kid in the candy store,” Gates recalls.

“I set out as my mission to bring as many superstars to the university as I could,” Gates recalls. True to fact, he sent for Hollywood: “My first appointment was Spike Lee! I hired Spike Lee to teach film for three years.”

The rest of the cast was as distinguished: novelist Jamaica Kincaid, philosopher Cornel R. West ’73, sociologists William Julius Wilson and Lawrence D. Bobo, historian Evelyn Higginbotham, and many more. “Eventually the press nicknamed us the Dream Team,” he says.

But dream teams are not made overnight. “Both Cornel West and William Julius Wilson had turned Harvard down,” he says. “I immediately went after both of them.” He pauses with a chuckle. “You could say, I was relentless.”

But if that was fast-paced work, what followed was slow, meticulous.

Gates set out on an odyssey. He explains how he went around to each department in the Faculty of Arts and Science soliciting joint appointments, before quickly qualifying: “Each that was relevant. I didn’t go to the Math Department. I didn’t go to Physics and ask for joint appointments for black holes.”

Gates also shied away from approaching the Classics Department because they predominantly studied European cultures – “they probably would have laughed at me,” he explains.

He speaks now with glowing pride about Emily Greenwood, the newly appointed professor of Classics and Comparative Literature, “the most brilliant Black classicist alive.” Next to Ancient Greek prose literature in her research interests sits postcolonial literature and theory. “It shows how the academy has changed over the last 32 years,” Gates says.

As the department began to take shape through jointly appointed professors – not least of them future Harvard President Claudine Gay – its influence would diffuse outwards to the rest of the academy.

“Our Ph.D. program has been successful, so successful,” Gates says, explaining that many of their students are now tenured professors.

But faculty was one side of the equation; on the other were many pressing concerns for Gates and the department – growing it intellectually, generating and soliciting funding, the easier-said-than-done business of keeping it running.

“He was the right man at the right time,” Wilson says. “He had a very sharp strategic sense of who the stakeholders were, what resources would’ve been necessary.”

“He came in and in the first year, he raised $14 million for the department. It was just incredible. After the department had been sort of limping along, he took it to lightspeed,” Charles Hamilton says.

If there is anything that has grown faster than the AAAS department under Gates’ leadership, though, it is his stardom. Racing from award to award, prize to prize, between PBS series and crowd-stirring New York Times headlines, all on the other side of his much-publicized wrongful arrest for breaking and entering into his own home, he has become a household name.

Despite the many spheres his life has straddled, Gates still seems most proud of the work he has done to take AAAS where it might not have gone. “It’s been a glorious ride,” he begins, “as I say, only at Harvard.”

“There’s an old saying,” he continues, “as Harvard goes, so goes the academy,”

Gates ponders as he looks out of his apartment-sized office in the Hutchins Center, which is situated in the center of Harvard Square. “That’s prime real estate!” he exclaims, “A sign of the faith and confidence that the university has in what we're doing.”

But Harvard is just one chapter of Martha Biondi’s nationwide survey, ‘The Black Revolution on Campus,’ published in 2014. With a view of the world past Massachusetts Ave., she says, “I think Harvard is part of a national story. It doesn’t stand alone, it really is part of a national story of elite institutions taking up this banner of ethnic studies and African American studies.”

“It’s both a leader, but also then a part of a broader development in academic life,” she adds.

In 2005, Gates realized that his time had come, and stepped down as chair. Now, the Department is taking a new direction, Gates says, with the appointment of Jacob Olupona as chair.

Olupona, a Nigerian-born professor of African and African American Studies and African Religious Traditions, was selected to head the Department earlier this year.

His appointment as chair comes at the most recent point along a journey to bring the study of Black people wherever they are — the U.S., Africa, the Caribbean, or beyond — to the focal point of the department.

This has always simmered beneath the surface – it was one of the demands made by protesting students in ’69 – yet it took until 2002 for anything to be concretized.

In 2003, the Department changed its name from Afro-American Studies to “African and African-American Studies,” after a joint effort by Gates and Emmanuel K. Akyeampong, who took the newly conceived department to FAS, explaining that “there was equal merit to the partnership.”

Akyeampong, born in Ghana, is a professor of History and African and African American Studies, as well as the faculty director of the Harvard University Center for African Studies.

In recent years, he has come to realize how valuable the reorientation of the department was. “When we started off,” Akyeampong explained, “I would look at African-American Studies and assume that race was the important lens.” In contrast, “for African Studies, our primary lens was development.”

The merger of the two into one department has brought Akyeampong to rethink this dichotomy. “In the last five or 10 years, I’ve become increasingly aware of how global Blackness has come to weld us all,” he says, bringing his outstretched hands together in front of his chest, his fingers interlocking, his knuckles meeting.

Akyeampong’s office in CGIS South houses an autumnal color-coded bookshelf, the spines lined with Frantz Fanon and many others of African studies’ big names.

He recalls a time, the ’50s and ’60s, in which the Black nationalists of the continent – Kwame Nkrumah, Julius Nyerere – met thinkers in the United States thinking through capitalism and slavery. “We’re beginning to see these conversations again,” he says.

Gates explains that in addition to the two streams of African and African American Studies, a third has been added: Afro-Latin American Studies.

The goal, Gates says, is to eventually have the same number of professors for each of the tracks: “The balancing act is to develop all three tracks equally.”

‘Born Out of Good Trouble’

{shortcode-be29865d8a9c7908fa05930b7f2d42574eaa573c}t was a very different department than it has become,” English Department Chair Glenda R. Carpio recalls, explaining that the AAAS department has changed a lot in recent years. “We used to have lunch on Tuesdays, and I believe it was a graduate seminar in which faculty also sat and discussed the readings. So it made for a great community.”

She clarifies, “This is back when Cornel West was still here, and when Professor Gates’ office was still in the department.”

Carpio cites Gates’s move from head of AAAS to Hutchins Center as one of the many changes that have signified a shift in the department.

“It’'s not intentional, but there was a lot of wanting to keep something, rather than let it evolve,” Carpio says. “I think there was a vision that Professor Gates had, and I think that vision, when he shifted away from being chair, I think it’s been hard to replace and to come up with a different vision,” Carpio says.

Carpio suggests that, perhaps what the Department needs now is a new “collective commitment.”

As she assesses the state of current AAAS’s faculty “energy,” Carpio assures us of the Department’s bright future as a new generation of professors join the department, including Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies professor Imani Perry, poet Tracy K. Smith, and art historian Sarah Lewis.

“The new generation will make new ground,” Carpio says.

Kojo Acheampong ’26, a co-founder of the current AFRO, also feels that the department needs to change by focusing more on “action.”

“Everybody wants to read ‘Souls of Black Folk’ by W.E.B. Du Bois. Everyone,” Acheampong says, lamenting the fact that Du Bois’ “seminal” text, “Black Reconstruction in America,” is often forgotten.

“Sometimes it feels like we’re wandering around and we’re just accumulating knowledge. But knowledge for what?” Acheampong says. “It’s cool, like we have enough libraries, and enough bookshelves, and enough books in the revolution. What we need is to move forward, that action.”

According to Acheampong, the Department has fallen victim to the ivory tower.

Recalling a moment in his “Intro to African Studies” course, Acheampong says the lesson — analyzing how the use of words like “underdevelopment” to describe the diaspora can do “more harm than wars” — felt “detached from the material conditions people go through.”

This detachment “creates a cycle of intellectuals and academics who just write, or they just be in academia, and they just sit in the ivory tower,” he says. “You’re doing the writing. Then, you’re self-validating your own role in liberation. And it was odd to hear that.”

Bobo, now the dean of Social Science, took a different view of the faculty in an emailed statement.

“Our faculty are not simply inwardly focused but many are influential thought-leaders, public intellectuals, and engaged citizen in the fullest sense of that phrase well beyond the boundaries of Harvard yard,” Bobo wrote.

A joint concentrator in AAAS and Government, Ebony M. Smith ’24, a Crimson Editorial editor, feels that the department has served her well. She applauds the department’s ability to both stand on its own as a concentration in its own right, as well as frame how joint and double concentrators approach their other academic interests.

“I think it enhances a lot of people’s core pathways,” Smith says, explaining that taking Black studies classes allows students to view their other academic work through the lens of racial equity.

Smith believes that the intersectional perspective AAAS allows for is important. “Being an inclusive member of a community makes you an overall better person,” she says.

Currently, Smith is writing a thesis on chocolate and its relation to the Black female body and femininity. Smith excitedly recalls her visits to the archives — reading letters sent by Angela Davis during her time in prison — and her deep dives into Black feminist and queer theory. Unlike Morisey five decades before her, Smith is no longer one of a few lone Black female voices on campus.

However, Smith says she knows the Department can be better.

“The African American Studies Department was born out of good trouble,” she says in a nod to John Lewis.

“I would encourage us to not stop — because there’s always more that we can get. There’s always more that we deserve. And there’s always a group of people who maybe don’t feel as represented yet,” she continues. “Don’t get too comfortable with where you are.”

Acheampong agrees. “The very origins of it is that Harvard was antagonistic,” Acheampong says. “That's the seed that planted, and it means that we have to continually be pushing for better in this department.”

‘It’s For History’

{shortcode-be29865d8a9c7908fa05930b7f2d42574eaa573c}n 2020, Dell Hamilton, the interim director of the Cooper Gallery at the Hutchins Center, set out to curate a history of the AAAS department to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Department.

She imagined this taking the form of an exhibit, but for one problem: photos could not be found.

“Black students essentially founded this department. Why aren’t there more images of Black folks?” she says.

After looking in magazines, newspapers, archives, and many other places, she stumbled across a photograph attributed to Lee Smith.

Smith remembers what came next. “Dell called me up and said, ‘We’re looking for some pictures,’ Smith says. “And I said, “You’ll have to be more specific. I have thousands. Tell me what you’re looking for.’”

Though for Smith, it seemed less important that his photographs feature in any Black studies retrospective than that what he documented be a part of the collective memory of the department. After giving his photos to Dell Hamilton for the exhibit, he donated his negatives to Harvard University Archives.

He freely sends the photobooks (“They’re knockdown gorgeous,” he says) and yearbooks he labored on as a student as PDFs to us; he carries hard copies around as he arrives on campus for this year’s yearbook reunion. Likewise, Charles Hamilton insisted that the Harvard Journal of Legal Affairs, which he helped to create, be a part of the source material for this article. Some 50 years later, this still matters to them.

{shortcode-b609630a661d1a96650eb77110ba38ab9b6889fb}

Talking to Smith about these years it’s as though he’s remembering last weekend. We ask him at one point if we can interrupt him to ask a clarifying question, and he stops immediately, signaling for us to go ahead. “I don’t lose my place,” he says.

“I have a personal commitment to this and I have an ancestral commitment to this as well. And it matters to me,” Wilson says as our interview comes to a close. If one thing is evident in the chain of events that birthed Black studies, it is that Black studies are intertwined with Black life. This holds true especially for the Class of 1969.

The people impacted by these events go beyond just the students directly involved, though.

“This reverberated in society and culture more broadly, as we see, in the decades after the achievement of Black studies on American college campuses, Black studies is a thriving and award-winning field of scholarship,” Biondi says. “It’s transformed reading lists and curricula across the country, and that’s had an impact also on filmmaking, theatrical production.”

Daniels happened to catch a glimpse of a faculty coursebook recently — it mystified him. “The course description to me was esoteric and then I realized, well, of course it is. It should be esoteric, right? Because I’m 50 years out. This stuff is new knowledge. There was nothing like this when I was an undergrad,” Daniels says. “To me, that was indicative of the depth of scholarship that is there in the department. And my gosh, this is wonderful.”

He was holding, in a sense, the fruits of his labor. When he and the other members of his class are asked what they fought for, they have today’s AAAS Department to show.

What, then, will today’s Harvard students — those who wish for the institution to change — have to show? Where there once were piles of petitions printed on white paper, signed by hand, and delivered to administrators’ doorsteps; today there are Google Document open letters that flood already-full inboxes and float into the Instagram ether.

The Greensboro sit-ins, the SDS-organized anti-war protest in Washington, the Soweto Uprisings in South Africa: student protests before the turn of the millennium have been remembered as watershed moments across history and are imbued with a certain valor.

The student protests of today, concerted though they are, seem to lack that same titanic quality. They make national news; but they don’t shake the center.

Not, exclusively, by any fault of their own — for faculty themselves in recent months and years have also found themselves pressed up against the modern impenetrable fortress of the university as institution, with its layers upon layers of red tape. Has the time when students might actually effect change at their university come and gone?

Smith returned to campus recently for a yearbook reunion; he seems as involved as he was when he was a student here. He appears to have a personal stake in the upkeep of the building, closing shelves left open, and switching off lights where no one is there.

Reflecting on his time photographing for the yearbook, he thinks especially about what its publication cycle afforded him. Because he was shooting for a yearly publication, he says, “The context was not for the news. It’s for history.”

There’s the sense that with or without the photographs, though, Smith would hold that history in him all the same. In an attempt to capture the moment in words, Smith turns to music: “The song, ‘Ain’t Nobody Gonna Turn Me Around?’ That wasn’t the phrase, but that was the essence of it.”

Smith says today: “Harvard has a different relationship with the class of ’69 because that class shut Harvard down.”

Correction: October 22, 2023

A previous version of this article stated the incorrect class year for Lee A. Daniels ’71.

— Magazine writer Sazi T. Bongwe can be reached at sazi.bongwe@thecrimson.com. Follow him on Twitter @sazibongwe_.

— Associate Magazine Editor Ciana J. King can be reached at ciana.king@thecrimson.com.