{shortcode-dcf7969ade1cbd376814ce09e5493121e683acb7}

Across the United States, many colleges and universities are struggling to fill seats.

Between 2009 and 2020, the number of undergraduates enrolled in American colleges shrank by more than 1.6 million. In Massachusetts, the rate of high school seniors immediately enrolling in college has dropped by approximately 10 percentage points over the last five years.

But as schools across the country scramble to meet enrollment goals, the Ivy League has the opposite problem.

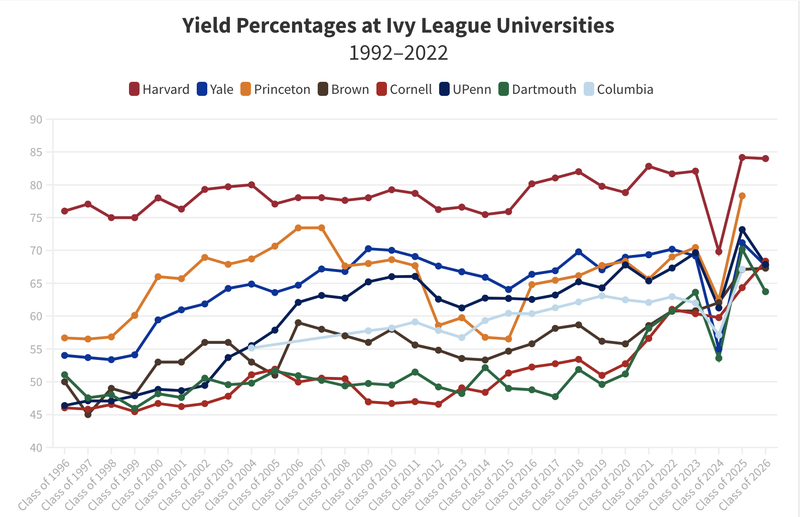

Yield rates at the eight Ivy schools have soared over the past 30 years, according to a Crimson analysis — and show no sign of slowing. At Harvard, the percentage of admitted students who choose to enroll has gone up by 8 percentage points since 1992. At most other Ivies, the growth is even more stark: Cornell has seen a 22 percentage point rise in its yield rate over the same period.

“I don’t think the yield landscape for the Ivies is going to change significantly,” wrote Brennan Barnard, director of college counseling at Khan Lab School. “At some point it gets high enough that there is not much room for improvement and it is unlikely to drop.”

The rise isn’t all an accident: highly-selective institutions have admissions tools that can manipulate yield rates, such as restrictive early action and early decision programs. And as ranking systems consider yield, universities often have an incentive to work to raise their rates.

“Like a lot of things in the college admissions process,” said Bari Norman, the co-founder of college counseling firm Expert Admissions, “It kind of finds its way back to the rankings, unfortunately.”

‘Trickle-Down’ Admissions

As yield increases at Ivy League universities, the number of students they accept has gone down: most Ivies take fewer students today than they did 30 years ago, though Harvard’s acceptance figures have remained steady.

At the University of Pennsylvania, nearly 5,000 students were admitted to the class of 1996 — compared to 3,500 for the class of 2026.

{shortcode-99abd7cda19b5a3ce5079aa75171ca0af1a7ea8f}

The trend is driven, in large part, by high yield. As the percentage of admitted students who choose to enroll increases, universities must admit fewer students in order to avoid over-enrollment. In turn, acceptance rates continue to plummet, which can translate into even higher yield rates, according to Barnard.

“The more selective a school is, people think that indicates quality,” Barnard said. “And therefore, they are more likely to yield at those schools, because they think it’s more desirable.”

The shrinking acceptance rates at Ivies also creates a “trickle-down” effect, said Hafeez Lakhani, director of Lakhani Coaching.

“There’s so much selectivity at the very elite places that really high quality students are trickling down” to other institutions, Lakhani said.

“The sort of winners in that argument are the Tulanes of the world, the University of Miamis of the world, the Americans of the world. It is harder to get into USC today than it was for me to get into Yale in the year 2000,” he added.

‘Early Bird Gets the Worm’

Yield rates often increase when early decision or early action programs are implemented — and tend to sink when the programs are taken away.

When Princeton eliminated its early decision program — which allows prospective students to apply early, but mandates that they enroll if accepted — for the class of 2012, its yield rate fell by 10 percentage points, the largest drop for any Ivy League school since 1992.

But following four years of comparatively low yield rates, Princeton reinstituted an early application program in the form of restrictive early action, which allows prospective students to apply and hear back from the school early without an enrollment requirement.

The following year, its yield shot up 8 percentage points.

“Schools are really defaulting to early decision plans,” Barnard said.

Harvard saw its lowest yield rates of the last 20 years when it eliminated restrictive early action starting with the Class of 2011. But after the program was brought back for the Class of 2016, yield rose by 4 percentage points.

“The early bird gets the worm, right?” Barnard said. “They’re getting their claws into students earlier, and so there’s a greater potential that they will yield them.”

Lakhani said that universities attempt to maintain yield in part to preserve or improve their placement in rankings from groups such as the U.S. News & World Report, which ranks universities annually.

“It becomes a little bit of chicken or the egg,” he said. “They’re protecting their yields because they know that if they're ranked 18 on U.S. News, it’ll get them more applicants than if they were ranked 26.”

“Without a doubt, people pay attention to rankings, even if it’s to their detriment,” Lakhani said.

Correction: September 29, 2022:

A previous version of this article incorrectly stated Brennan Barnard's current job title.

—Staff writer Rahem D. Hamid can be reached at rahem.hamid@thecrimson.com.

—Staff writer Nia L. Orakwue can be reached at nia.orakwue@thecrimson.com.

Read more in News

Harvard Study Identifies Key Role of Soil Moisture on Crop Yields