{shortcode-ca4da223a1a941a487ed38650789e16f900b286b}

On Tuesday, March 8 — International Women’s Day — an odd assortment of protesters from the organization RiseUp4AbortionRights set up camp outside the CVS in Harvard Square. They wore green legwarmers and bandanas — a nod to the recent Green Wave of reproductive justice movements in Latin America. They had covered the walls of the nearby T-station elevator with black-and-white posters depicting women who died from illegal abortions before the procedure was legalized in 1973. Passersby could flip over the portraits to read each woman’s harrowing story.

The protestors, mostly middle-aged, held colorful, hand-made signs with messages like “Forced Motherhood is Female Enslavement” and “Abortion on Demand and Without Apology!” To anyone who would listen, they handed out free T-shirts with their organization’s name and a simple graphic depicting a clothes hanger crossed out with a red X.

Meanwhile, tourists and Harvard students walked past. Though organizers had handed out and plastered posters around campus over the previous weeks, of all the demonstrators, only three were Harvard students — two of whom were the authors of this article, there to cover the rally.

The striking absence of Harvard students that day was not an anomaly.

Most Harvard students are in favor of abortion rights — nearly 80 percent of college students nationwide say abortion should be legal in most or all cases, compared to about 60 percent of US adults. But despite — or perhaps because of — Harvard students’ above-average consensus, this support in principle does not always apply in practice to concrete action on campus.

This conspicuous absence has not always been the case.

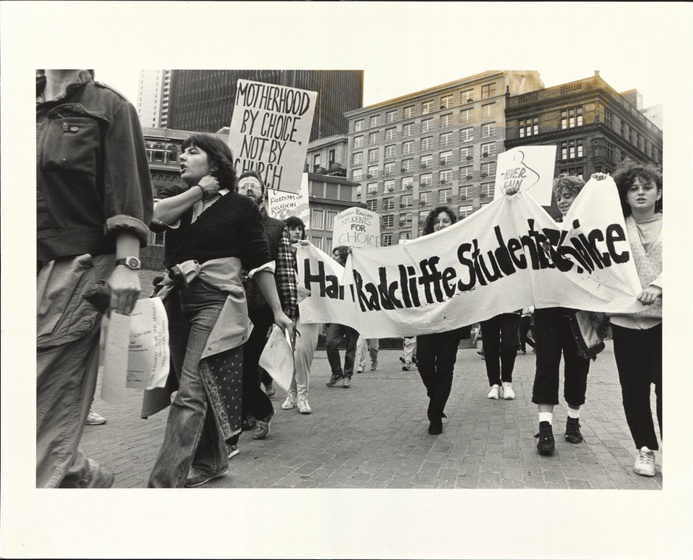

Since Roe, activism surrounding reproductive issues has ebbed and flowed on campus, loosely mirroring the political climate of the time. In the ’70s, immediately following the Roe decision, Radcliffe women pushed to expand reproductive justice. In the ’90s, anti-abortion and abortion-rights student groups held fervent debates, swapped editorials in The Crimson, and posted flyers on dorm room doors. And in the mid-2010s, abortion rights groups revamped and evolved to center lived experience and equity concerns in their advocacy approach. But by contrast, today’s campus culture surrounding abortion-related issues is relatively quiet — leaving a vacuum all the more striking in the face of looming national threats to abortion access.

In June, the Supreme Court is expected to release a decision on Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, a case regarding a Missouri abortion restriction that directly violates Roe v. Wade, the landmark 1973 case that legalized abortion in the United States. Currently, over 40 million women live in states hostile to abortion — and without Roe’s protection, that hostility would translate into severely restricted access to the procedure.

Mary R. Ziegler ’04, a professor at Florida State University College of Law and a national expert on abortion law, is curating an exhibit at Harvard’s Schlesinger Library to celebrate Roe’s 50th birthday next January. But she is unsure whether the ruling will reach the milestone. When asked about the probability of Roe being overturned, she says: “It’s not really a question of if — it’s a question of when.”

This lack of activism on Harvard’s campus may be reflective of a larger national ignorance or resignation about how likely Roe is to fall, and the devastating consequences that change would enact.

According to George Stevens, one of the organizers of the Women’s Day rally in the Square, the public does not appreciate the gravity of the situation. “People have the capacity to come out in the hundreds of thousands, but yet it's not happening now, in part because they think somebody else is going to do it for them,” he says. “There's a need to sound the alarm — that this is an emergency here that needs to be responded to.”

{shortcode-158f981872cdd9547f3919b748951fa5de608ec6}

But Harvard students perhaps also reflect a particular generational malaise. According to Kathy Lawrence, another organizer of the rally, unlike her generation — which grew up in the ’60s and ’70s — today’s would-be activists don’t remember the gruesome reality of pre-Roe abortions: “The younger generation don't know what it was like when abortion wasn't available. It was women using coat hangers, it was women committing suicide, rather than carry the pregnancy to term, women throwing themselves downstairs,” she says. Most Harvard students, along with the rest of Generation Z, have grown up in a world where Roe is doctrine. But that doctrine may very well change soon.

This generational complacency contributes to a lack of activism, which along with a culture of silence around abortion on campus, obscures the real ways in which Harvard students experience abortion — as well as their connections and potential contributions to the current national crisis around abortion rights.

How has a right codified into law nearly fifty years ago become more and more tenuous as the years have marched on — and what underpins the dissonance between students’ complacency and the urgency of their current reality? Let’s go back in time.

‘We’ve Won This’

“Have You Gotten so Liberated That You’ve Forgotten How to Cook?” jokes a 1979 advertisement in Seventh Sister, a Radcliffe monthly journal. “Practice by Coming to Seventh Sister’s Pot Luck Dinner!”

Billing itself playfully as “not just another collectively run women’s newspaper existing as a positive alternative to competitive hierarchical journalistic institutions,” the radical publication was founded in 1977 to fill gaps in feminist discourse and coverage on campus. “This was the new journal, by women, for women at Harvard, and there was this real political commitment that we weren't going to do things the way men did things,” says Tanya M. Luhrmann ’83, a contributor to Seventh Sister. “We were going to be more collective, we were going to work together.”

{shortcode-c7a846ebfb8f6390ebe791d881a700241e0c6b54}

Out of its office on the third floor of Phillips Brooks House, Seventh Sister published content ranging from opinion pieces on sexual double standards and the liberation of Black women to features on Salvadorian refugeee women in Boston to personal essays on feminist spirituality and ‘Exploring a Gay Lifestyle.’ The newspaper also published reported pieces on topics like the experiences of student mothers at Harvard, and notably on the recently established abortion right.

To secure a safe abortion before Roe, women in Boston with the means to do so often traveled to New York, where the procedure had been legal since 1970. But by February of 1973, just a month after Roe constitutionalized abortion, the Crittenton-Hastings House in Brighton was licensed to perform abortions, becoming the first free-standing clinic in Massachusetts. By April, the “Crit” started seeing patients. According to the 1974 Harvard Medical Alumni Bulletin, the clinic performed around 400 abortions in its first four months.

In addition to Crittenton-Hastings, a handful of other free-standing abortion clinics obtained licenses and opened within a few months after Roe — meaning that for those with the means to pay for it, abortion was largely accessible in Boston in the late ’70s and early ’80s.

Luhrmann and her Seventh Sister contemporaries recall the turmoil associated with illegal abortions pre-Roe — a cultural memory that younger generations lack. “We were much closer to the recognition of what happens when abortions were not available: back alley abortions, hanger abortions, and how hard it was for people without resources especially,” Luhrmann says. “So we really had a sharp sense of the importance of a woman’s right to choose.”

{shortcode-a838dace6bfbaf23c2ff2b9263a7f2518a52c922}

That understanding underpinned the urgency with which Harvard-Radcliffe women spearheaded abortion education and advocacy efforts on campus. For example, in the spring of 1978, Seventh Sister co-hosted “Abortion Educationals” with the Dunster House Women’s Issues Table, a group that aimed to foster conversation surrounding gender issues, and the Boston-based Abortion Action Coalition.

Occurring just a few years after Roe, these advocacy efforts took place in a culture where abortion’s legality was not particularly contentious. “It was kind of a sense of ‘we’ve won this, we have this, the Supreme Court has decided it,’” says Susan D. Chira ’80, the second female President of The Crimson.

That sense of security meant campus activists could look beyond abortion to issues like unequal access to reproductive healthcare and to forced sterilization, specifically of Native American, Black, and Latinx women. During the “Abortion Educational” meetings, speakers would introduce abortion legislation and related reproductive justice issues, and students would debate issues surrounding abortion: birth control, daycare, and forced sterilization among them. As one student quoted in Seventh Sister said, “the issue of abortion is not abortion.”

One contributor, Indigenous activist and then-undergrad Winona W. LaDuke, argued in an opinion piece for broadening the scope of “pro-choice,” noting that while the government should not force its citizens to become mothers by prohibiting abortion, it should not deny them the opportunity either through forced sterilization.

In another Seventh Sister article that spring, a student reported on the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare hearings in Boston about forced sterilization. One Native American woman, Dawn Gore, testified about being forcibly sterilized in Holyoke, Mass., while going to the hospital for a routine appendectomy. The Committee to End Sterilization Abuse reported instances of Spanish-speaking women being manipulated into consenting for the procedure in Boston hospitals.

{shortcode-29ee2cd86fe2d51393e6a815fb177156b0367c07}

Though there was scattered opposition to the reproductive rights movement, there was no unified or organized anti-abortion movement on campus at the time. In 1979, Luhrmann wrote an editorial titled “The Pro-Choice Argument” — one which, 50 years later, still makes the rounds of The Crimson’s top five most-read pieces online. “I remember thinking that abortion was so obviously a woman’s right that you just needed a good argument,” recalls Luhrmann, “not that people really and truly thought that it could be murder.”

But when someone sent the printed page back to her with a “red, baby-killing slur” on it, she reevaluated her belief that Harvard was majority in favor of abortion rights. “I remember thinking, ‘Huh. There’s more variety of opinion here than I thought.’”

Chira echoes Luhrmann’s inklings of growing dissent from pro-life voices. “At that point, the power of the anti-abortion movement was not clear,” Chira says. “We underestimated the power of sincere religious belief.”

‘Have Pro-Choicers Aborted Ship?’

It was not uncommon for Shannon E. Lowney to walk past anti-abortion protestors on her way into work at the Planned Parenthood in Brookline, Mass. — and the morning of December 30, 1994, was no exception. She had moved to Boston that fall to pursue a degree in social work, and she was working as a receptionist and a translator for Spanish-speaking women.

Around 10 o’clock that morning, a young man entered the clinic dressed in all black. He approached the desk and asked, “Is this Planned Parenthood?” Lowney smiled and replied that it was. The man then took out a semi-automatic .22-caliber rifle and shot Lowney multiple times in the throat before opening fire on the clients and visitors in the waiting room.

The man, John C. Salvi III, then went to Preterm Health Services, another abortion provider two miles down the road. “Is this Preterm?” he asked. The receptionist, Leanne Nichols, answered that it was. Salvi shot her five times.

Nichols died at a hospital that day; Lowney died at the scene.

In the aftermath, Bernard F. Law, then-Cardinal of the Archdiocese of Boston, called for a moratorium on protests outside of abortion clinics while urging the public not to conflate the shooting with the anti-abortion movement as a whole: “I would request that this tragic and criminal act of apparently one individual not become the occasion of universalizing blame.”

That a cardinal would respond publicly to the shooting signified a change in public discourse around abortion — by this point, abortion had grown to signify more than a medical procedure: it was a battleground for religious and moral issues, and increasingly polarizing ones at that.

Between the hopeful activism of the Seventh Sister era (the magazine published its last issue in March 1984) and the violence of the mid-’90s, a shift occurred in American political culture: the Reagan Era. Leading up to the ’80s, religious organizations like Moral Majority aimed to turn abortion into a litmus test for Republican candidates, using religion to associate abortion with murder and politicizing the resulting fervency to bring Evangelical voters to the polls. Reagan’s decision to make his opposition to abortion central to his successful 1980 presidential campaign solidified its place as a tenet of American conservatism.

{shortcode-b3ca93472fd276a4778eb926d92a34524a68a165}

In 1992, in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the Supreme Court gave the green light for states to enact abortion restrictions that did not pose an “undue burden” for a woman seeking an abortion. With the first major legal modification to Roe, activism on Harvard’s campus turned to focus on the right to abortion itself as opposed to larger reproductive justice issues — and a formal anti-abortion movement took root.

In 1998, Harvard Right to Life, an organization focused on anti-abortion advocacy, launched its first major campaign. Borrowing an idea from Harvard Law Students for Life, HRL encouraged students on the University’s health insurance to request a refund for the portion of their Student Health Fee that funds abortions, arguing that students should not have to pay for a procedure they disagreed with on moral grounds. HRL ran the campaign each year until at least 2004, then again in 2008, and most recently, in 2019.

While HUHS does not perform abortions, its physicians can refer students to nearby clinics and reimburse the fees for those on the Student Health Insurance Plan. As a result of these campaigns, HUHS now reimburses students who request it the portion of their Student Health Fee that goes towards abortions: $1 per term.

The seventh year in a row that HRL ran its opt-out campaign, The Crimson ran an editorial criticizing the University for issuing such refunds — not because of the concession to the anti-abortion movement specifically but because of the slippery slope of its logic. Vegetarians, the writers argued, are not able to request a refund for the portion of their meal plan that goes towards meat, even though they might have moral issues with it; the policy of issuing refunds, therefore, “exclusively favors pro-life students’ moral obligations.”

In addition to the opt-out campaign, HRL members posted bright yellow posters of fetuses in utero on doors and walls around campus — accompanied by captions like “Did you know: my heart is already beating!” “‘A person’s a person no matter how small.’ — Horton Hears a Who!”. Arianne R. Cohen ’03 responded with a Crimson column criticizing the group's strategy. “The posters are astutely designed to pluck the heartstrings of a scared 19-year-old college girl who just found out that she’s three weeks pregnant,” she wrote.

Meanwhile, Harvard Students for Choice, the main abortion rights organization on campus, hosted speaker events and debates in accordance with their mission statement: “While the group will provide access to activist opportunities, its primary concern is education.” In 2003, to counter HRL’s anti-abortion postering, HSC organized its own campaign urging students to put a sign on their door stating they did not want “anti-choice propaganda” in their doorbox.

By 2006, though, the abortion-rights pushback to HRL’s opt-out campaigns consisted of scattered individual student efforts to tear down the posters in their own Houses. In an op-ed for The Crimson entitled “Have Pro-Choicers Aborted Ship?”, one student criticized HSC’s failure to mount an organized response to HRL’s campaign: “Harvard hardly seems to have a pro-choice lobby at all. While the official student group Students for Choice claims to ‘promote greater awareness and understanding of [reproductive] issues in the Harvard community by means such as publications, meetings, seminars, and debates,’ it would appear only to exist on facebook.com.”

HSC leadership responded with its own op-ed claiming that after a turnover in leadership, the club would be making a “strong comeback” with more events. However, it is difficult to find evidence of this resurgence, as HSC is notably absent from Crimson coverage of the abortion debate after 2006, and the HSC website has not been updated since 2003. Instead, it lingers on the internet as a relic from the turn of the century, its guestbook overtaken by spam bots — a nail in the coffin of the fervency that characterized activism of earlier years.

‘Out of Silence’

It wasn’t until the mid-2010s that a club devoted to reproductive justice was active again on campus: the International Women’s Rights Collective. Grappling with a student body neither hostile to nor proactive about abortion — and a campus culture largely silent on the issue — organizers worked to rekindle a ’70s-era urgency that would make the presence of abortion at Harvard more real in students’ eyes.

IWRC was founded in 2011 by Rainer A. Crossett ’14 and Kate J. Sim ’14, who told The Crimson at the time that she was frustrated by the “lack of radical feminist vision I imagined I would be getting involved with [at Harvard].” The collective aimed to organize events on issues ranging from educational disparities to climate change in the context of gender equity.

Over time, though, their focus narrowed. “As years went by, the issues that became the most salient and inspiring — [the events that] were most well-attended — were things around abortion,” says Caroline N. Goldfarb ’18, a member of the club at the time. In 2017, Goldfarb proposed that the group embrace this new focus and rename itself to reflect the shift. The ReproJustice Action Dialogue and Collective was born. RAD is the most recently active abortion-rights group on campus.

Reproductive Justice refers to a movement founded by Black women in the ’90s to broaden the focus beyond the upper- and middle-class white women to whom the abortion-rights movement largely catered. Taking this ethos to heart, RAD focused on making sure women of color sat on the board and held events on intersectional issues like forced sterilization, deemphasizing the abortion right and centralizing access, contraception, autonomous childbearing, and parenting more broadly.

RAD consciously used language that moved beyond traditional abortion rights rhetoric. “The classic pro-choice language and approach wasn’t feeling as updated,” Goldfarb says. “The new framework was reinvigorating.”

Goldfarb says the transition from IWRC to RAD reflected a new sense of exigency engendered by the Trump administration’s overt antagonism toward reproductive health care. “The national mood was becoming more hostile to abortion, and [event] attendees were reflecting that,” she says. From cutting millions from teen pregnancy prevention programs to stacking federal courts with judges opposed to to abortion, attacks on access to abortion were becoming more visible on a federal level over Trump’s tenure as president.

IWRC and later RAD engaged in programming like phone-banking, visiting clinics, collecting signatures to overturn the Hyde Amendment — which bans the use of Medicaid funds to pay for abortions — tabling at the Science Center, and hosting movie screenings.

Members also worked to make abortion more visible, countering abstract discourse with concrete storytelling. Recalling a debate the Harvard Political Union hosted every year or two on abortion, former IWRC president Brianna J. Suslovic ’16 reflects that “people are inclined to make everything into an intellectual debate or abstract topic to converse on.” IWRC and RAD tried instead to be specific about the lived experiences of individuals getting abortions both on and off campus, grounding their rhetoric in a “humanizing and non-shaming and non-presumptive approach to understanding the experience of abortion as a medical procedure.”

{shortcode-612d375c368e9a23c26d5435cd2a98cc4f3fc1f0}

These stories came to life during the groups’ annual “Out of Silence” performances, where student and community actors would perform a series of vignettes about real individuals’ experiences with abortion.

For Suslovic, “Out of Silence” was powerful because it reduced the stigma attached to abortion — especially at a place like Harvard. “There's a lot of racialized and class assumptions that mean that people don’t often think of Harvard students as being in scenarios with unwanted pregnancies,” she says. “So complicating that a little bit and offering some sort of real-life storytelling [was] really, really exciting to see.”

Goldfarb recalls that members of HRL would attend the events and participate in the open discussions afterwards, of which she was “totally welcoming”; open dialogue was key to the “Out of Silence” mission, she says, and the conversations never became hostile.

RAD and IWRC struggled to receive the institutional support they needed for programming like “Out of Silence,” relying heavily on external support offered by nonprofits like Advocates for Youth — whose 1 in 3 Campaign put on similar performances at hundreds of college campuses nationwide. Suslovic also recalls another external organization, the Boston Doula Project (now the Boston Abortion Support Collective), which offered a workshop instructing students on how to support a friend who has just gotten an abortion: “bring them a bag to throw up in, saltines and ginger ale, a heating pad to use when they get home.”

“We never felt like we were in a hostile environment, but [we weren’t in] an actively supportive environment either,” Goldfarb says, expressing her wish that Harvard administrators had been more enthusiastic to engage with reproductive justice issues.

RAD dissolved over the pandemic, and it has not been revived since. Goldfarb says that Harvard makes it very hard to have an official club — from creating a bank account to filling out paperwork, there’s “a lot of red tape.” Groups like the Institute of Politics have tangible resources like advisors, buildings, and funding to ensure the organization’s continuity. But activist groups do not receive the same support.

Meanwhile, HRL is still somewhat active — last semester, they hosted speaker events with leaders from organizations to end euthenasia and provided financial support to struggling mothers.

“Currently, we live in a pro-choice world,” says Ava A. Swanson ’24, one of HRL’s co-presidents, “So when a woman chooses life, our pro-life organizations need to be there to support her and her child.” Swanson cites financial support, adoption reform, and foster care reform as alternate options to abortion.

But HRL is nowhere near as visible a campus presence as in earlier decades, while RAD remains defunct.

“The problem with student groups that are not institutionally supported at the College is they’re very dependent on the people in them,” says Goldfarb. She adds: “It makes it really hard to run a sustained advocacy campaign on a campus through a student group.”

‘Experiencing Abortion’

Even as activism has come and gone across Harvard’s history, one thing has stayed constant: Harvard students have sought abortions for almost 50 years — and no matter the prevailing political climate, the experience is intensely personal.

Abigail (a pseudonym) was 19 when she found out she was pregnant at Harvard, according to an anonymous account published in the April 1979 issue of Seventh Sister.

“Having an abortion at Harvard is simple and safe,” she wrote in a piece titled “Experiencing Abortion.” “It is so simple and so easy that I still haven’t been able to get over my terror and shock.”

{shortcode-bf8c45ed94b9dbb8d9032890702cf9b94817791a}

Abigail walked into University Health Services to take a pregnancy test feeling “nervous and embarrassed,” she wrote. She had recently broken up with her boyfriend, and she came from a “loving but conservative” family.

The nurse delivered Abigail’s positive pregnancy test along with the phone numbers of social workers who could help her with her decision. But for Abigail, it was no question: “I knew exactly what I was going to do, and I was going to do it. And I felt guilty and miserable as hell.”

The procedure occurred just three days later, at the nearby Crittenton-Hastings Clinic. Abigail notes that UHS covered her costs and connected her with a guidance counselor who scheduled the procedure. It was quick and simple and “not even very painful.”

Yet the administrative ease with which Abigail obtained the procedure could not erode the intense guilt she experienced. “All my conscious instincts, all my supportive friends and counselors were trying to convince me I had done the right thing, and all my innermost prejudices were trying to tear me apart,” she wrote.

Thirty-six years later, in another anonymous account — this time published in The Crimson — Emma (a pseudonym) told a similar story of her experience receiving an abortion through Harvard. Her 2015 account, entitled “Pregnant at Harvard,” references the name of an abortion resource pamphlet she had seen in the Harvard College Women’s Center as a freshman. At the time, she had written it off at the time, joking about it with her friends. She never thought she would actually need it.

But two-and-a-half years later, as she walked out of an abortion clinic in Boston, she wondered if she should have picked up that pamphlet.

Like Abigail’s abortion, the most painful part of Emma’s wasn’t the surgery itself but its emotional aftermath. “When it was over, I screamed. I couldn’t stop screaming,” she wrote. “As I write these words, it has been over a month since the abortion — and on the inside that screaming hasn’t stopped.”

Neither woman expressed regret over her decision, but both cited a disconnect between the ease of access to abortion and its emotional toll. “You can make abortion as easy and available as you want,” wrote Abigail, “but until you erase several hundred years of vocal cultural criticism against women and sexuality, the experience will always be a damning one.”

Emma pointed to a culture of silence on Harvard’s campus as a contributing factor to her distress. Despite weeks of her vomiting nearly every day, skipping class, and wearing baggy clothes, none of her roommates, friends, or classmates noticed anything out of the ordinary. “It is frightening how hard it can be to find support at Harvard,” she wrote.

She pointed to how little institutional resources can mean if that support isn’t there. “We know there are a million campus resources, no matter what you’re going through,” she wrote. But “actively reaching out is impossible to do. You want someone to come to you.”

The process of getting an abortion through HUHS is still as simple as Emma and Abigail described. Students can go to HUHS for a preganancy test or a referral to a nearby abortion clinic, which is reimbursed by student healthcare.

Toochi A. Uradu ’22 is working to align campus culture with the institutional support Harvard has to offer. As part of a project for her Activist, Collaborative, and Engaged Interventions in Anthropology class, Uradu is working with the Women’s Center to create an updated guide to reproductive health resources at Harvard.

But, she notes, in order for those resources to be effective, they will have to become destigmatized.

“People don’t really talk about needing these resources or their experience with these resources,” she says. “There aren’t any statistics about how many Harvard students are seeking an abortion, which is weird to me, because it makes this community out to be invisible.” Uradu partially attributes Harvard’s culture of silence to its culture of perfectionism — that people don’t like to admit that things aren’t going “as they’re supposed to.” She adds: “People could be going through it alone, and we would never know.”

Harvard’s culture of silence is reflective of a broader discomfort with abortion, stemming partially from an underrecognition of how commonplace the procedure is nationwide. According to a study from the Guttmacher Institute, nearly one in four women will get an abortion before they turn 45.

“It’s multiple people in every room you’d go into,” says Goldfarb, who managed an abortion clinic after she graduated. “The disconnect between our collective understanding of what abortion access looks like and who gets abortions and the reality of what it means to get an abortion, is a huge gap that we have to close as we alert everyone how urgent the situation is.”

Goldfarb’s clinic was one of only four all-trimester abortion clinics in the country — meaning she saw the most socially, medically, and financially complicated cases. “At the clinic, you’d have a 13-year-old, followed by a 42-year-old doctor in a prestigious medical center, followed by a 27-year-old mom who’s a teacher,” Goldfarb says. “I’ve had people wear Trump hats while they’ve gotten their abortion. I’ve had people say ‘You’re murderers, and I hate you, and I’m here for my abortion.’”

There is no singular experience of abortion. For each woman who exercises her right to choose, the experience can vary in emotional and physical difficulty. Chira, for example, who got an abortion after graduating Harvard, did not struggle with the same emotions as Abigail and Emma.

“It was absolutely crystal clear. I did not feel moral guilt,” Chira says. “I felt lucky that I had access to something that allowed me to become a mother when I wanted to become a mother — when my life circumstances allowed me to give birth with joy and support.”

‘Stare Decisis’

Fifty years ago, Chira never could have imagined that Roe would be imperiled today. “I think it would have been hard for us to believe, you know, stare decisis, that something settled could be so …” Chira says, trailing off. Stare decisis refers to the legal principle that cases should be decided based on precedent — and has operated as a key element in protecting Roe over the past few decades.

But now, Chira has accepted that Roe will likely soon be overturned. “All the tea leaves point to it,” she says.

Though activism has ebbed and flowed, the looming threat of Roe falling would not be just another tide — it would radically curb abortion access nationwide and force activists to entirely reevaluate their strategies. In a world without Roe, each state would get to decide whether it wants to grant the right to its citizens.

According to FSU professor Mary Ziegler, state-by-state laws have historically played an integral part in the “patchwork” of abortion access in the U.S. as it exists today, stratified along lines of age, religion, income, and race. Twenty-six states are certain or likely to ban abotion the moment Roe is overturned.

{shortcode-2ee2d4d160e363f9c95ead630a8d179eaf67c0e0}

Many women in these states would either seek illegal abortions or seek care in other states: a New York Times analysis showed that the majority of women denied abortions by Texas’s September heartbeat bill found another way to get them — either via medication abortion or travel out of state.

Since Massachusetts is unlikely to illegalize abortion, students would still be able to get abortions through HUHS. In fact, in 2020, Massachusetts passed the ROE Act and became the first state to remove a parental consent requirement for 16-18 year olds seeking an abortion. Still, Harvard students would not be entirely immune to the aftermath of an overturned Roe, given that they only live on-campus during the academic terms, and therefore may be located in non-abortion-friendly states for much of the year.

Ziegler brings up an even more sinister possibility: that women could be prosecuted in their home state for an abortion they received in Massachusetts. “If a student is from Alabama, and they have an abortion while they're at Harvard, and then they return to Alabama, and somehow someone gets wind of it — [what would happen] if Alabama tries to prosecute them?”

Some activists believe that Roe’s being overturned would re-light a spark in liberals who have become largely complacent on the abortion issue. Another potential long-term silver lining could be a constitutional “blank slate” on which to inscribe a newly articulated abortion right.

Speaking to the ways that abortion could be constitutionally grounded, former Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote an article in 1985 asking whether Roe would have been better decided with a rationale related to the way that abortion is a tenet of gender equality, not just privacy. Ziegler explains what equality has that privacy lacks: “it recognizes that abortion is an issue of discrimination, for trans men and non-binary folks, [as well as] racial discrimination, which is obviously central to how abortion works in the real world.”

Ziegler notes that Biden’s new Supreme Court pick, Ketanji B. Jackson ’92 — who, if confirmed, would be the first Black woman to serve on the Court — will likely not have any impact on Roe’s fate. However, she will be significant in bringing an awareness of how race intersects with abortion access to the Court’s left wing, which Ziegler says has been “stunningly absent” in case law up to this point. Explaining how the new justice could impact future doctrine, Ziegler points out that “today’s dissents are tomorrow’s majorities.”

Goldfarb emphasizes that legality, ultimately, is only one part of the equation. “Abortion is something that is only there so much as we’re able to get people to it,” she explains. She firmly believes that every individual has something tangible to contribute to expanding access, whether it’s donating to an abortion fund, manning a hotline, acting as a clinic escort, or paying for someone’s gas to get to a clinic.

As the Roe decision looms — and, along with it, the reality that scores of women will die and be harmed irreversibly if or when the case is overturned — there is still no publication like Seventh Sister, no club like RAD, and no rally in the Yard to spotlight the issue here at Harvard.

— Magazine writer Sarah W. Faber can be reached at sarah.faber@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @swfaber.

— Magazine writer Kate S. Griem can be reached at kate.griem@thecrimson.com.