{shortcode-9498ef105bf1fb118d34afc96e7135f675725365}

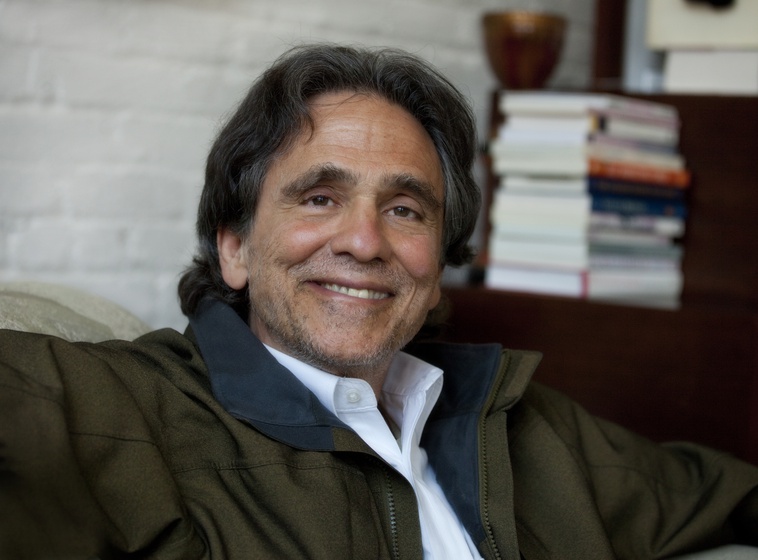

When Ted J. Kaptchuk was recruited by Harvard in 1995, he was considered anything but orthodox. He had training in traditional Chinese medicine — a field Kaptchuk says is often written off as “forbidden” and “non-scientific” in Western academic circles. His first task was studying the extent to which the healing properties of alternative medicine might be due to the placebo effect, a phenomenon new to Kaptchuk at the time. One of his colleagues defined it as the “effect of an inert substance.”

When Kaptchuk heard this, he thought, “Oh boy, this is an oxymoron.”

Feeling that much of the debate over whether alternative medicine was “just” a placebo “had all kinds of hidden biases,” Kaptchuk immersed himself in studying the placebo effect — a topic “no one cared about” at the time — not just as it related to alternative medicine, but in general. Now a full professor, he’s one of the few faculty members at Harvard Medical School with neither an M.D. nor a Ph.D., and a leading scholar in the field of placebo studies. He’s proud of his status as a self-proclaimed “black sheep” at Harvard — he says that being “different in socialization has really made [his] career what it is.”

As a total history buff, Kaptchuk does not want to study anything without understanding its historical context. When he began researching the placebo effect, he discovered that its history was much longer than many people at the Medical School thought, and “unsavory on lots of levels.”

According to Kaptchuk, countless studies utilize placebo controls, but those only provide information about the placebo response compared to the actual treatment. There are very few studies on the placebo effect, which compares the results of those treated with the placebo with those who received neither treatment nor a placebo.

To address the need for more knowledge on the placebo effect, Kaptchuk began studying whether this phenomenon exists at all, and if it can be manipulated. He was particularly interested in whether it was possible to control the level of placebo effect induced in a subject.

He looked at specific patient populations — people with asthma, for example — to determine whether or not placebos can cause objective changes in health and physiology. Kaptchuk says this study marked a first, as other research in the field had focused on the perceived effects of a placebo, rather than objective changes.

Still, Kaptchuk is also interested in less quantitative research. In another study, he collaborated with an expert in Tibetan medicine and analyzed patient interviews. “As I read the transcripts,” he says, wide-eyed, “These people are totally different from what my mentors told me, that they think it’s the drug and that’s why they get better.” In fact, the patients all worried they were on the placebo.

“They were petrified that their improvement was because of what was going on inside their heads,” he says.

In an interview for the study, Kaptchuk recalled one of the patients responding, “I’ve been to four specialists with this disease. I came into this study because I’m desperate. Why would I think I’d get better? I’m hopeful that I’ll get better. If I didn’t have hope I wouldn’t be able to get out of bed.”

For Kaptchuk, hearing this changed everything. Perhaps, too, it signalled some form of change, however small, within the larger field of placebo studies. Kaptchuck says this study — his favorite of the projects he’s led — was the first in the field where patients were interviewed about their placebo experiences.

“Placebos, in my feeling, are a marginalized entity in medicine,” Kaptchuk says. “Placebo research, really until recently, has been based on deception, tricking people by giving them placebos and telling them it’s a real, powerful drug.”

“My work is taking the placebo out of the closet — taking it out of the marginalized,” Kaptchuk says. He hopes to do away with the saying “Oh, it’s only a placebo!” and start reinforcing the belief that “No, there’s something here, and you don’t have to be dishonest.”