When a peculiar commotion roused him from his sleep on January 4th, 2007, Paul N. Gailiunas ’92 wasn’t wearing his glasses. His wife, Helen W. Hill ’92, grappled desperately by the front door of their home with a figure whose outline Gailiunas could hardly make out in the dawn light.

In a CNN article from 2007, Gailiunas recalls seeing the intruder throw Hill aside and step through their kitchen with his arm outstretched, handgun grasped tightly between his fingers. Then, three loud bangs. Silence.

When police arrived on the scene minutes later, they found Gailiunas kneeling by the door, clutching his son in his arms. One bullet had pierced his cheek; another had sliced into his arm and hand. The last bullet had struck Hill in the neck.

It was an unusually humid winter morning in New Orleans, and thunderclouds had gathered around the city’s edges. Long before medical assistance reached her, Hill had breathed her last.

“It seemed absolutely unimaginable that she had died in this way,” recalls Vineeta Vijayaraghavan ’94, a former Crimson editor. While at Harvard, Vijayaraghavan and Hill had worked together on the same women’s literary magazine, The Rag. Hill had mentored Vijayaraghava, who was two years her junior.

“It seemed like a horror show,” Vijayaraghavan says, remembering the day she got the news.

Before long, however, that horror show repeated itself: on July 19, 2014, Dan E. Markel ’95, a prominent criminal law professor, was shot and killed outside his home in Florida. Markel was a class behind Vijayaraghavan, a friend from Lowell House. In September of the following year, Carey W. Gabay ’94 was caught in the crossfire of a New York City shooting, leading to his death a week later. Gabay had served as president of the Harvard College Undergraduate Council, one of the first African-American students to do so.

“It felt like maybe once in your life, random chance means that someone, somewhere in your world will experience something horrible like that,” Vijayaraghavan reflects, “but then to have it be just a few years later and have Dan killed, and Carey killed—” Her voice trails into silence.

“How is this the state of saturation that we’ve hit with gun violence? How is it that this could happen three times?”

In March, Vijayaraghavan put her frustrations into print, arguing in an op-ed for USA Today that there exists “no pocket of privilege safe enough” to shield oneself or one’s children from gun violence.”

“My Harvard classmates were shot in the head in separate incidents in three states,” she writes. “Their elite educations did not protect them from gun violence.”

***

Every December, St. Rose of Lima Church in Newtown, Conn. holds a famously elaborate Christmas pageant. I remember attending in 2012 and seeing the church parking lot’s manger scene complete with a real-life donkey and a living, breathing cow. My hometown was a short drive from Newtown, and each year our church sent a delegation to the pageant. This year, the event was crowded with people packed body-to-body, all holding taper candles.

A week earlier, a gunman had entered Sandy Hook Elementary School, only a mile or so from St. Rose, and shot and killed 20 schoolchildren and six adult staff members. It was at that time the deadliest mass shooting in American history, and the nation was reeling.

After the pageant, we walked past the main street where Anderson Cooper had begun to record a segment and arrived at the entrance of Sandy Hook. We were met with a sea of twinkling candles, heaps of flowers, collections of teddy bears, children’s toys, all surrounding an unassuming wooden sign, painted white: “Sandy Hook School,” it read. “Visitors welcome.”

Five years later, in the wake of the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, where 17 people were killed and five wounded, gun violence has again come to dominate national discourse. But there is a sense that this time things are different. This time, we have refused to remain silent in our mourning, to accept a reality in which such events could ever occur. We walked out of our classes; we marched for our lives. Across the country, we made a vow: #neveragain.

Yet in focusing attention on Newtown, on Orlando, on Las Vegas, on Parkland, the media narrative risks painting gun violence in one shade: the mass shooting, the freak incident, the unpredictable tragedy. Doing so allows for the dismissal of tragedies like Sandy Hook as anomalous incidents in otherwise insulated communities, not symptoms of a much larger phenomenon—a phenomenon that one Los Angeles Times columnist calls “as American as baseball.”

Remembering the deaths of Hill, Markel, and Gabay—three individuals whose time at Harvard overlapped—Vijayaraghavan writes that their elite educations did not protect them from gun violence. And yet, underpinning her statement is the curious assumption that their alma mater could have shielded them from bullets in the first place.

Research demonstrates that gun violence—when deaths by suicide are removed—disproportionately affects underprivileged, urban communities, especially young black men. These deaths often receive little attention. It is when gun violence seeps into suburban enclaves like Parkland and Newtown—in dramatic incidents that seem unimaginable—that major news outlets arrive on the scene.

“[Mass shootings] get the news, but depending on how you count a mass shooting, they only constitute 1 to 2 percent of firearm deaths,” says David Hemenway ’66, a professor at the School of Public Health who studies gun violence. “It makes people very fearful,” he continues. “We spend huge amounts of time—large amounts of it probably wasted—trying to protect schools against mass shooters.”

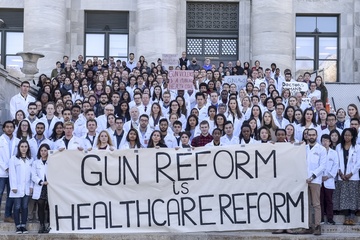

Instead, Hemenway advocates for a comprehensive public health approach to mitigating gun violence. “The public health approach is all about prevention rather than waiting for bad things to happen,” he explains. “The goal would be to agree as a society that we have a very serious problem and take a step back and try to get everyone to play their part to reduce the problem.”

Hill died in post-Katrina New Orleans; her murder was one of six in a single 24-hour period. She and Gailiunas had moved back to the city because they wanted to play a role in rebuilding the community where they had fallen in love. Gailiunas, a doctor, was treating low-income patients in an emergency health clinic; Hill was offering animation classes in a cafe. Hill’s death—that of an idealistic, Harvard-educated filmmaker in a city ravaged by crime and systemic neglect, doesn’t fit cleanly into any recognizable image of gun violence.

Gabay, a lawyer working in the administration of Governor of New York Andrew M. Cuomo, was shot while attending the West Indian American Day Parade in Brooklyn; Markel died in what appears to have been an elaborate contract killing plot. Though there seem to be as many narratives of gun violence as there are victims, some display more visibly than others: this is in part due to racial and class disparities, which are exacerbated by deliberate legislative obstacles.

Hemenway cites the Dickey Amendment as a major hurdle in the path towards a realistic conversation about gun violence. The amendment, a 1996 congressional provision, effectively prohibits the Centers for Disease Control from using public funds to research gun violence. “The gun lobby didn’t like the results of early research funded by the CDC that found that having a gun in the house increases, not decreases, one’s risk of death,” Hemenway says, referencing a landmark 1993 study that challenged the narrative often repeated by the National Rifle Association: that gun ownership allowed individuals to better protect their families.

The Dickey Amendment has brought public research on gun violence to a standstill. “I’m an economist by training, and I’ll tell you—people go where the money is,” Hemenway says. “When there was no money for AIDS research, we didn’t do any AIDS research. If you want more research done, you have to be able to pay the researchers.”

If, as Vijayaraghavan argues, a Harvard education cannot protect those who wield itfrom the epidemic of gun violence, maybe it can equip them with the tools to combat it.

“When I think of an epidemic—like the measles outbreak that we recently had in Orange County—I know we have a way to combat it,” explains Mai Khanh T. Tran ’87, a pediatrician challenging Republican Representative Ed Royce for his seat in California’s 39th Congressional District.

“We have data, we have science that we can put together to curb and mitigate it,” Tran says. “We don’t have that sort of data for gun violence—why? Because we have an act in Congress that prohibits us from collecting gun violence data.”

If elected, repealing the Dickey Amendment would be among her top priorities, Tran asserts. “We need people in Congress who will look at science, look at data, and approach gun violence as the true public health crisis that it is,” Tran says.

Tran joins another Harvard alumnus, Lauren E. Baer ’02, a former Crimson editor, in seeking gun reform by running for office. Florida’s 18th Congressional District, which Baer hopes to represent, is only an hour north of Parkland. Baer herself lived in the town as a child, completing fifth grade at Park Springs Elementary School, just down the road from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School.

“It’s important for us to recognize that gun violence is a pervasive problem in our country—it’s not just an issue of mass shootings,” she argues, highlighting how the problem weighs heavily on underprivileged communities, minority groups, and victims of domestic violence. “We need to be thinking about the gun violence epidemic in a holistic way that addresses the many ways in which it impacts our country and the many communities that it affects in particular.”

***

“Helen would have invited this person in. When we went for the funeral, I can’t tell you how many times I heard people say that,” Keiko K. Morris ’92 recalls, referring to the intruder—to this day still unapprehended—who killed Hill, her college roommate. “She would have asked them what they needed and given them something to eat—that to me was so tragic. She was so kind, so generous.”

Morris’s anecdotes from college are vivid and free-flowing: She recalls easily Hill’s optimism, her sense of adventure. The duo would “literally sleep on the common room floor” in Thayer after dancing to Cat Stevens late into the night. “I remember on week nights she would just say, ‘Let’s go and traipse around downtown Boston’ or ‘Let’s go to the top of the John Hancock Building,’” Morris adds.

Morris remembers well the day another one of her senior year roommates delivered news of Hill’s death. “It was surreal—it just floored me,” she says. “I couldn’t get my mind around it.” Morris, who had taken her love of writing to the Wall Street Journal, found herself at a loss for words: “I had covered crime for many years. I had done interviews with many people who had recently lost family members to violence, but I had never thought that I would be on the other side of it.”