It was the summer of 1974 when the letter arrived. Imani Kazana was informed her services as Director of Harvard’s Afro-American Cultural Center—services that included building maintenance, filing paperwork, and on one occasion, birth coaching—were no longer necessary. She wasn’t surprised.

Kazana, who was in her second year as director, says she knew the cultural center was fighting an “uphill battle.” She says the University helped students scrape together about $100,000 when the center was first founded, but didn’t help raise money as time went on. Soon, the center’s funds dwindled.

“We did start trying to solicit donations and that kind of thing, but it wasn't anything close to what we needed,” she says. “Nothing close.”

Two years prior, Kazana’s personal life had seen a whirlwind of changes. She took the helm of the cultural center that year and also changed her name.

“When you're looking at the Harvard archives, you're probably going to find my first name—my previous names will come up first, so I better tell you what they were,” Kazana cautions. “Don't put it in the article. I don't want people to go backwards, I want to move forwards.”

Kazana’s outlook is future-focused. But in many ways, her last name—which means “united effort and strong force” in Swahili—informs the past as much as it does the future. It would soon become an apt descriptor of her work with the cultural center, of campus activism before her time, and of the ongoing struggle decades after her departure.

{shortcode-94f50dabb04e201f9abf15209ebb4fd359a04ae4}

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, as the landscape of affinity groups on campus evolved, a consistent theme has been the struggle for space—space to gather, space to make minority voices heard, and space in the University consciousness as a whole. Activist initiatives focused on the establishment of an academic department, a research institute and a cultural center. The last of these is yet to be established on Harvard’s campus, and an Undergraduate Council coalition is currently seeking to create a space for minority students.

Kazana was one player in the fight for this space—a fight that has stretched over decades and across different student groups; a fight that continues today.

Before there was a cultural center, there was the student group that pushed for it.

In those days, the Harvard-Radcliffe Association for African and Afro-American Students—AFRO for short—was the primary black student group on campus.

The year was 1963, a decade before Kazana would receive word of her termination. The Beach Boys’ “Surfin’ USA” was at the top of the charts. In November, the president of the United States was assassinated. Martin Luther King marched on Washington that summer.

AFRO earned College approval as a student organization in December.

Before Harvard officially recognized AFRO, its foundation was shaky. The group was initially rejected by the Faculty Committee on Student Activities because of its membership clause: “Membership in the Association shall be open to African and Afro-American students currently enrolled at Harvard and Radcliffe.” The Harvard Committee for Undergraduate Affairs deemed the clause “discriminatory.” In December, AFRO voted to reword its membership clause to exclude “African and Afro-American” identity as a requirement for membership.

AFRO went on to become instrumental in sparking changes that swept Harvard and Radcliffe throughout the ’60s and early ’70s. The group undertook a variety of initiatives—ranging from staging sit-ins in support of affirmative action to inviting James Baldwin to speak in Sanders Theater in 1964.

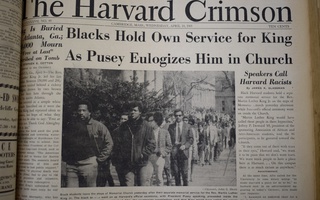

“We were a place for black students to talk about issues, politics, debate what was going on in the country and what our role was in it,” says Jeffrey P. Howard ’69, who served as president of AFRO in its early years. “And after Martin Luther King was killed, we turned to real political activism—we engineered the University’s adoption of an Afro-American Studies department and the cultural center, the DuBois Institute.”

Though Carol B. Allen ’75 is listed as vice president of AFRO in archival records of the club, she says she doesn’t remember being vice president. In fact, she doesn’t remember much about the club at all.

“I don’t have fond memories of being in college. It really wasn’t a great experience for me personally,” Allen says. “So I just have a few vague memories here and there of things that [AFRO] did.”

But she does remember what it was like, broadly speaking, to be a black student at Radcliffe in the 1970s. She recalls that, at both Harvard and Radcliffe, black students tended to be clustered together in the same houses, and that students sat together based on race in dining halls. She also says there was competition between black students. When she applied to medical school, she remembers feeling as though all of the black students were competing for one spot.

{shortcode-0b2236437d87b4d896cf14b6cb5490bbfb4fdd32}

“There was a lot of competition among ourselves, as opposed to what I felt should’ve been real bonding,” she says.

But for Constance B. Hilliard ’71, the first memories of AFRO that come to mind are personal and overwhelmingly positive.

“It was just so important to my life as a student at Radcliffe,” she says. As she describes her time in AFRO over the phone, she effuses warmth, offering anecdotes unprompted.

“And it was important because there I was, an African-American student in an environment that I really wanted to be in, in terms of my studies and learning and so forth, but I just—I felt alienated, and I felt very, very lonely,” she says. “It was a lifesaver. It saved my life.”

“With that being said, I can't think of anything that really stands out, except that for some reason, we seemed to go to a lot of meetings,” she adds, laughing. “And what did we do? I don't know. There was always some reason for us to meet.”

As she speaks, the web of Hilliard’s memories begins to unravel, evolving into a vivid account of AFRO’s initiatives throughout the ’60s. She gradually remembers the activism she was involved in as a member, all closely tied to invaluable changes that bolstered Harvard’s efforts to increase racial equality.

Hilliard, for instance, recalls a sit-in designed to promote increasing enrollment of black students at Radcliffe. According to Assistant Professor of African and African-American Studies and Social Studies Brandon M. Terry ’05, before 1968, there were just a handful of black students accepted at Harvard and Radcliffe each year. Then, in 1969, following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. the number jumped to over 100. “That assassination basically changed everything,” Terry says.

Hilliard’s undergraduate years included this transition. She also remembers AFRO being involved with the fight for the establishment of what was then called the African and Afro-American Studies Department.

In response to the assassination, the University created a Faculty Committee on African and Afro-American Studies—chaired by Henry Rosovsky—which came to be known as the Rosovsky Committee. This committee initially announced that there would be an African and Afro-American Studies “program,” which students perceived as inadequate. Hilliard says that students fought back after this announcement, which ultimately led to the establishment of an autonomous department.

“We also fought for a cultural center, and then a W.E.B. DuBois research center,” she says, and she laughs again. “So now I remember—that’s why we had all those meetings.”

Hilliard and Allen have vague memories of the Afro-American Cultural Center. Hilliard says she remembers that it was “always hard up for money.” Allen says she remembers there being a room in a building. But both say the cultural center did not play a significant role in their undergraduate years.

Nonetheless, William G. Fletcher ’76, another member of AFRO, distinctly remembers Kazana and her efforts to energize the Center.

“Imani was someone, at the time, in her early 20s. She was always encouraging people to come by, to drop in, to hang out there, to have meetings there, so it was a very comfortable, a very safe place,” Fletcher says. “It was definitely a hang out for the black radicals, and not just black radicals—it was a very comfortable space. And I don’t mean just physically comfortable, but you felt like you could be who you were.”

The use of the Sacramento Street space was rooted in policies laid out in the late ’60s. The Rosovsky Committee published a report in 1969 that provided guidelines for implementing an African and Afro-American Studies department and recommended the creation of a cultural center.

Henry Rosovsky, the former Economics professor who chaired the committee, declined to comment on the developments of the AAAS department and the center. Now 90, Rosovsky wrote in an email that he only has vague memories of this time.

Sociology professor Gary T. Marx, who served as one of the youngest members of the committee, says the case for the cultural center rested largely on the need for peer-to-peer cultural exchange.

“The argument was that blacks had to define black culture and express to others, blacks and non-blacks, what it was about,” he says. “It has lots to do with that kind of issue—who can speak for a group?”

Marx’s course Sociology 110: Race and Ethnic Relations was a “happening” on campus in the late ’60s–unenrolled students would drop in to his lectures, using the information as a grounding in which the University community could “[speak] truth to power in a civil way.” This Enlightenment notion of universal access to knowledge, Marx says, underpinned many of the arguments in favor of the cultural center, which would provide space for sharing diverse lived experiences and build a humanistic collective culture for the college.

Following the Rosovsky Committee’s recommendation, the University established an Afro-American Cultural Center Committee was established in late 1969. The committee raised enough money to purchase a building at 20 Sacramento St. that same year.

The cultural center was a three-story Victorian house. The first floor featured a large room—formerly the living room or parlor—that was used for meetings, socializing, and a variety of other periodic events: art exhibits, holiday parties, etc. The second story had four or five rooms occupants designated as offices and administrative space. The third story comprised bedrooms.

For some, the cultural center was a home. The third-floor bedrooms often housed groups that visited campus—Kazana particularly remembers when a Rastafarian cultural group from Jamaica stayed over. And the center also housed “a handful” of Harvard students who couldn’t afford room and board, Kazana says. She agreed to put them up in exchange for “helping out” around the center.

Kazana says she interacted with students she met through the center in unexpected ways. Once, a woman asked her to be her birthing coach.

“In my second year there, because there were few women around, black women, there was this young graduate student,” Kazana says. “She came to me, she said, ‘I’m alone and I really don’t have anyone that I feel comfortable with that I can call upon to be my coach, so will you do this for me.’ So I said okay. I literally went to classes with her, and I was there at the hospital to help her get through the labor process and to give birth to her child.”

Kazana applied and was hired as director of the center shortly after graduating from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst with a degree in African-American Studies in 1972. Students ran the search for a director by themselves, she says—and, aside from Kazana and a secretary, the administrative board of the center consisted wholly of work-study students.

The center briefly shared the Sacramento Street space with a daycare center primarily for minority children. Today, the building houses a feminist counseling practice.

Though the center was intended mainly for African-American students, Kazana says the space was home to student groups of all kinds–groups that focused on issues ranging from socialism to anti-apartheid activism. Kazana says she had a dream the cultural center would eventually expand into a space more in line with the Undergraduate Council’s vision of a multicultural center today.

“I remember quite distinctly that we became very close to a small group of Chinese students and they didn’t have any place at all, so this is how we kind of got into the idea that when we could expand and get bigger and better, at some point we would want to become a third world student center and expand our membership to everyone—all people of color,” she says.

Yet the center didn’t suit the ideals of every black student. George H. Yeadon III ’75, a member of AFRO, says he saw the cultural center as a “knee-jerk reaction” to the protests of the late ’60s. He thought the University was trying to be helpful—but he thought Harvard did not know how to go about it the right way.

Yeadon, who doesn’t live in the Boston area, is in town for a Harvard Alumni Association conference. The lobby of the Charles Hotel where we meet is nothing short of chaotic, humming with the excitement of alumni catching up with old friends and reminiscing about their glory days. In the midst of this collective remembering, Yeadon pieces together his college experience.

The Cultural Center wasn’t a hangout spot for Yeadon or his friends, he says, adding that “more radical” groups would use the center as a meeting place.

Nevertheless, the Center left a lingering mark on some. Two years ago, one of the students Kazana once housed at the Center phoned her to thank her.

“I interviewed him, and we agreed to let him live there in the Cultural Center, on the third floor. We gave him some responsibility, and he told me that that was really the first time that anybody had ever given him a responsibility,” Kazana says. “And that was what most impressed him—not so much that he had a place to live, which he obviously did, because he didn’t have an option. But he said that I had shown faith in him, as a human being, to be responsible for something.”

Kazana remembers a push in the spring of 1974 for the relocation of the Cultural Center to 74 Mt. Auburn St., a bigger and more central building. Ultimately, this push was unsuccessful, and the Center continued to struggle for money. That summer, Kazana received the letter from the University declaring her services no longer necessary.

Though the summer of 1974 marked the closing of the 20 Sacramento St. Cultural Center, student efforts and activism for the establishment of a Third World Cultural Center—the multicultural center that Kazana envisioned—persisted. Other physical spaces on campus devoted to diversity cropped up and promptly disappeared throughout the ’70s and ’80s. In 1975, a center opened at 1750 Cambridge St, and in 1978, a flyer listed 17 South St. as the center’s location. None lasted.

The 1970s saw changes in the landscape of black student groups on campus, allowing new organizations to take up the fight for a physical space. Following the “petering out” of AFRO, as one BSA member put it, the Harvard-Radcliffe Black Students Association earned official recognition in Dec. 1977.

{shortcode-19c0e444ebf65a012b08872ef22a62cf17eec595}

Fletcher and several other early members of the BSA remember a Mass. Hall “takeover” as a poignant moment of activism. The takeover, which aimed to combat Harvard’s indirect support of South African apartheid via its oil holdings there, is one of the few events that stand out in Allen’s memory.

“I remember the chant that we used to use as we were circling around outside, which was ‘U.S. out of Southeast Asia, Harvard out of Gulf,’” she says. (Others remember the same chant, word for word, after nearly 50 years.) “So that's the thought that comes to mind whenever I think about action back then. I believe I was a freshman at the time, so that would've been ’71, ’72. Derek Bok was the president at that time.”

Derek C. Bok became president of Harvard in 1971. He wrote in an email that he “vaguely” remembers an African-American student center springing up in 1969, before he took the position. “I also remember a sit-in by black students in Massachusetts Hall during my first spring in office, but that was led by a law student and, in any event, I had no contact with the students involved during and after their occupation,” Bok writes.

June V. Cross ’75, who reported on racial activism for The Crimson, compared the Mass. Hall demonstration to the Occupy movement. Students camped out at the administrative building for six days.

“It was awesome,” Cross says. “It was a coming-together and a sense of possibility and change, in a mass action against the administration. It felt like we actually achieved something.” (By the late ’80s, Harvard “selectively” divested from its Gulf oil holdings.)

Fletcher says that many of the people who were involved with the takeover formed a group that he called the “Black Collective.” He adds that in the AFRO board elections of 1973, the members of this collective refused to run for positions because they felt that AFRO was “going to fall apart.”

1973 also marked the advent of several new groups on campus that further decentralized AFRO: the Organization for the Solidarity of Third World Students and a Harvard chapter of the national February 1st movement—a “black radical organization”—among them.

The OSTWS, Fletcher says, “brought together radical students, black, Asian, Latino, to work together, and it lasted until I think about ’75. And it became a major site for some of the more politically active black students.”

When the BSA formed on campus in 1977, it sparked controversy similar to that which AFRO faced in its infancy, according to Cross. Cross says this tension is reflective of the racial climate black students faced at Harvard broadly.

“I think our entire existence on campus was being questioned,” she says.

In November of 1979, the BSA distributed a newspaper called Nexus, covering topics from the W.E.B. DuBois Institute to the African and African American Studies Department. The paper lists six objectives under the headline “BSA Confirms Themes and Goals,” the second of which is “establishing a Third World Cultural Center.”

Aaron A. Estis ’80, a member of the BSA, remembers that, for a brief time, the University again provided a location for yet another short-lived Cultural Center.

“Somehow or another, some other activists in BSA convinced the University to give us access to this building. It was really just a small little house,” he says. “We called it the Afro-American Cultural Center. And so we were successful in getting that. It was important because we used it to organize events and activities and people could meet there.”

John A. “Tony” Butler ’80, another member of the BSA, also recalls the fight for a cultural center, but says his memories of the openings and closing of various centers are unclear.

“I do remember that we were trying to get it to be reopened or get another location for it. I remember something about us trying to get it reinvigorated, reestablished,” he says. “But I don't recall physically where we were gathering.”

When we ask Anthony R. Chase ’77, BSA’s first president, if the group had a physical space, he just laughs.

The shuttering of the Sacramento Street Afro-American Cultural Center in 1974 did not end the debate about whether there should be a physical space on campus for students of color. Many of the same threads that defined campus discussions around the Afro-American Cultural Center in the ’70s still hum today, as student activists on campus push for university support of a physical space for belonging.

Since the closing of the Afro-American Cultural Center, the University has orchestrated other initiatives to foster inclusivity and diversity on campus. Bok wrote in an email that, in response to requests for a Cultural Center, the University instead created the Harvard Foundation in 1981. Bok wrote that the Foundation “did a great job under the leadership of the late Allen Counter of bringing students of all races together in a series of projects over the ensuing years.”

But while the Harvard Foundation does work to promote better race relations on campus, it still does not provide a physical space for students of color.

“The Foundation does incredible work, but it's not a place where students go and sit and hang out and have gatherings. The students, besides the interns, don’t feel as though they own the space,” says Nicholas P. Whittaker ’19, a co-chair of the Undergraduate Council’s “Multicultural Center Coalition,” which aims to eventually create a physical space for belonging on campus.

“That’s the same for most of the physical spaces on campus that are dedicated to these sorts of issues,” Whittaker adds. “They're dedicated at an administrative or policy level. That's not a bad thing. We need those spaces, too. But what we’ve realized is students are not looking for just another Harvard Foundation.”

Salma Abdelrahman ’20, the other co-chair of the UC’s multicultural center coalition, says she believes the University should have responsibility beyond just providing a location for a multicultural center.

“A commitment means financial support, it means being willing to hire staff, it means being willing to put those measures in place in order to make this a long-term thing that is stable and that has a presence on this campus for longer than four years,” she says.

It seems these concerns mirror the landscape of 1972, when students themselves ran the job search for the director of the Afro-American Cultural Center. Also still relevant is the connection between a physical space on campus and space in the University consciousness broadly. Whittaker offers the example of final clubs—traditionally all-male, exclusive social societies housed in mansions in the middle of campus that have come under administrative fire in recent years.

“We wouldn't have spent this much time and energy as a campus and a community discussing them if they hadn't had so much physical space. Essential to the conversation was the physicality of their presence on this campus,” Whittaker says of the clubs.

In the same way, Whittaker says, a physical space on campus for students of color would draw attention to and foster conversation about relevant issues.

Whittaker also says that the underground venues occupied by the Harvard Foundation and other diversity offices means the groups are “tucked away from the rest of the community.” The Women’s Center operates out of the basement of Canaday, the Diversity Peer Educators’ and BGLTQ offices are in the basement of Grays Hall, and the Harvard Foundation is located in the basement of Thayer Hall.

In response to these criticisms, Roland S. Davis, Associate Dean for Diversity and Inclusion, wrote in an emailed statement the Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Office prioritizes accessibility.

“One of the most important parts of EDI’s mission is to make sure that everyone feels welcome and that students can get to our offices easily,” David wrote. “To that end, we are delighted to now have all of our offices located in the yard. In addition, it is important to note that our new space in Grays Hall is fully ADA accessible, which is a huge improvement over their previous space.”

Whittaker’s criticism of these offices’ locations recalls the flaws that led to the original cultural center’s demise. Bill Fletcher points to its lack of centrality as a reason the building was ultimately unsuccessful. Students had to make a conscious effort to go there, he says.

Today, they have nowhere to go.

When we tell Imani Kazana about the current debate over a multicultural center, she responds with a short burst of laughter.

“It’s never happened? Oh Lord, okay,” she says. “That’s sad.”

—Magazine writer Nina H. Pasquini can be reached at nina.pasquini@thecrimson.com, Follow her on Twitter @nhpasquini.

—Magazine writer Sophia M. Higgins can be reached at sophia.higgins@thecrimson.com.