In late January, Harvard Management Company announced it was changing course: it will largely cut its internal management teams and retain external managers to handle almost all of the University’s $35.7 billion endowment, laying off approximately half of its staff.

Only two internal teams of managers will walk away from the changes intact: the firm’s natural resources team, which HMC will continue to manage in-house, and its highly-successful real estate branch, which is expected to strike off on its own to form a hedge fund.

{shortcode-648e55506d0122a5444423849bd0885c8da6aa6d}But experts say that if the real estate team—which earned a 20.2 percent return on its investments in fiscal year 2016—continues to do business with HMC as an external management unit, it could earn salaries well above what members of the team drew in at HMC for doing mostly the same job.

For Charles A. Skorina, the head of a firm that conducts searches for financial executives across the country, this is not necessarily uncommon for the investment industry.

“It’s fairly common to see an internal group at an endowment that’s done well spin off and retain an investment from the endowment,” Skorina said. “Now they’re an outside firm and one of their key investors is the endowment they came from. That’s normal. That’s not shocking.”

Harvard Business School lecturer Randolph “Randy” B. Cohen said the relationship between HMC and the newly-formed real estate hedge fund could take a number of forms. Harvard’s investment arm could request “preferential terms of some sort” from the hedge fund, like superior access to the fund’s talent and increased liquidity in its assets, among other things.

As external managers, the members of the real estate team stand to make even more money for providing the same services to Harvard’s investment arm. But Cohen said the newly-formed hedge fund might not hike up its asking price in return for business from HMC, one of the most prestigious investors in higher education.

“We might expect HMC will pay them more to be on their own than they paid them to be employees, but we don’t know for sure, " Cohen wrote in an email. "Maybe the opportunity to build a business, with the prestige of HMC as their first investor, is sufficiently attractive that they’re willing to do the work for HMC for no more than they received when on staff, or conceivably for even less.”

Skorina agreed that though the newly-formed hedge fund will have the opportunity to set the price of its services at market value—significantly higher than what it is paid internally by HMC—it will likely grant its former employer a discount.

As of right now, HMC’s real estate team is the only investment cohort that is expected to continue to do business with Harvard. But the firm’s natural resource assets will continue to be invested internally, even as HMC cuts its 230-person staff roughly in half.

Roger G. Ibbotson, a professor at Yale, said shortly after the announcement of the changes that large endowments shifting to external management would keep a specific asset class managed in-house for one of two reasons. It might happen if the asset class performed extremely well—an unlikely case for Harvard’s natural resources investments, which returned negative 10.2 percent on its investments in fiscal year 2016—or was too difficult to sell off in the current market.

Skorina said the real estate group is the “only team they [HMC] cited as winners,” and that it was unlikely HMC would seek business with its other investment teams if they decided to spin off.

“I think [HMC chief executive officer N.P Narvekar] was pretty clear that performance wasn’t up to snuff,” Skorina said of HMC’s other teams. “Why would Harvard give people who perform poorly inside money? Why would Harvard then invest with them when they’re outside?”

The sweeping changes in investment strategy—which some experts say indicate an attempt by Narvekar to recreate the investment strategies of peer institutions like Columbia and Yale—mark the investment chief’s first public moves as he sets off on the task of improving Harvard’s struggling endowment.

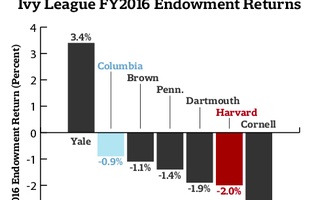

In fiscal year 2016, Harvard posted the lowest returns on its investments since the height of the financial crisis, returning negative 2 percent on its investments. Combined with other expenses, including the $1.7 billion Harvard allocates to its annual budget from the endowment, the endowment’s value fell nearly $2 billion in fiscal year 2016.

—Staff writer Brandon J. Dixon can be reached at brandon.dixon@thecrimson.com. Follow him on Twitter @BrandonJoDixon.

Read more in News

Faculty Meeting Agenda Set Without Lewis MotionRecommended Articles

-

With Narvekar’s Appointment, Seeds of Change at HMC

With Narvekar’s Appointment, Seeds of Change at HMC -

Three Investment Managers To Depart HMC to Form Hedge FundsWeeks after the Harvard Management Company announced its intent to lay off nearly half of its 230-person staff, three of the firm’s investment managers will leave the company to form their own hedge funds, according to Bloomberg.

-

Alumni Group Critiques Harvard’s Investment Strategy in Letter to FaustMembers the Class of 1981 suggested significant changes to Harvard Management Company’s investment philosophy in a letter to Faust.

-

HMC Will Invest At Least $300 Million to Spun-Off Hedge FundMonths after announcing it would radically revise its investment strategy by the end of the fiscal year, Harvard Management Company will invest at least $300 million into a hedge fund formed by some of its former money managers.

-

HMC Aims to Sell $2.5 Billion in Endowment Assets

HMC Aims to Sell $2.5 Billion in Endowment Assets