Last Friday, I sat on a bench outside of the Gutman Library for two hours, waiting for a man named Richard Scarbrough.

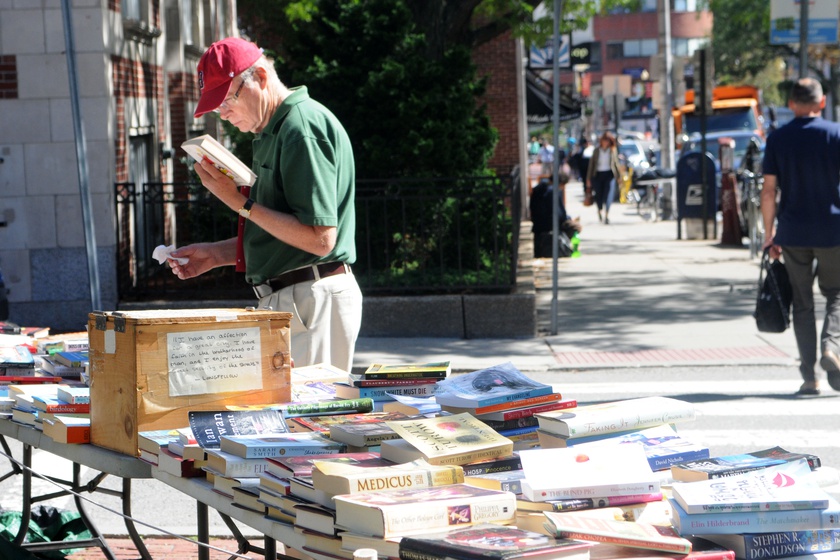

Richard Scarbrough is the proprietor of a bookstore on the corner of Brattle Street and Farwell Place. The store consists of two folding tables, stacked piles of books, and a wooden box with a slot for cash.

Various notecards taped to the box read:

“‘I have an affection for a great city. I feel safe in the neighborhood of man, and enjoy the sweet security of the streets.’ – Henry Wadsworth Longfellow”

“Bitcoin”

“HONOR SYSTEM: Books are priced as marked on the front cover. If you find a book that you want, please pay by putting the money in this box. I have been selling books on the streets of Cambridge for over 10 years thanks to this awesome community and good people like you. Thank You!”

{shortcode-121a326bcd61852f6e0f2fca3d338e71a29b5a4c}

Somebody asked me a question about pricing, bringing the total number of times I’d been mistaken for the owner up to three.

I was there because I had been told that Scarbrough’s bookshop was, in addition to a form of supplementary income, a “libertar- ian economic experiment.” I had next to no clue what that meant, but I did think that the system worked well. In the five or so unsuccess- ful hours I’d sat by the store that week, I did not see anybody steal. Most people browsed, and left. I think I saw one or two purchases.

While Scarbrough’s political views are particular, his collection spans the whole range of literary taste.

{shortcode-383899fa854458608645186acbcf6af86c244d33}

Al Franken’s autobiography sits alongside a book called “Beauty Queen,” whose cover fea- tures a bikini-clad torso sporting a bandolier holding lipstick in place of bullets; self-help books of every shape, size, and scope, “9 Steps to Financial Freedom,” “Interviewing your Daughter’s Date: 8 Steps to No Regrets,” and “7 Habits of Highly Effective People”; critically acclaimed works: “Musicophilia” by Oliver Sacks and John Berendt’s “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil”; and enough cookbooks to account for every genre of American regional cuisine.

By Wednesday, I was confident I had found all that the Internet had to offer about him: a Twitter account that went inactive around November 2014, a Yelp review of the book- store (five stars, but only one reviewer at time of writing), and a FundAnything page that expired in 2013 after raising $60 of its $15,000 goal. He created to raise money for a real brick- and-mortar bookstore on Garden Street.

I found one email address associated with the FundAnything page, but Scarbrough did not respond to my message.

Finally, around 8:15 p.m., a sensible mid- size sedan rolled up and a balding slightly- below-middle-aged man stepped out of the car, lit a cigarette, and leaned on his car smok- ing, clearly waiting for two young women to finish browsing the book piles. From a picture on his Twitter, I was certain that it was Richard Scarbrough.

“Gotcha,” I actually found myself whisper- ing, like the detective from a cheap noir.

Once the women dispersed, I introduced myself and told Scarbrough that I’d like to write about him. He was there, as he is every night the store is open, to close up shop, a pro- cess which consists of spreading a large tarp over the books and anchoring it under the legs of the table. I helped out and we chatted. He became very friendly after I assured him that I wasn’t “one of those communists on The Crimson.”

He had a gregarious, slightly nervy energy that I couldn’t help but like a little.

The store, confirming what I had heard, is indeed a libertarian economic experiment. Specifically, Scarborough terms it a “peaceful revolution through counter-economics.” The idea is that one doesn’t need a permit or a set of complicated laws or regulations to sell things.

{shortcode-0bc105c7e62c6bd4215c05098bae1bbc5075a436}

Scarborough was particularly invested in Libertarian political philosophy that night because of a tiff he had gotten into during the day with a city official who had asked if he had the proper permits to paint the shop he is starting. The shop will be funded with the revenue “Honor System Books” has accrued over 10 years (daily earnings range from $20 to $75). It’s Scarbrough’s latest move in a life spent selling books. Before he moved his busi- ness to Harvard Square, he ran a stall in Copley where he sold his own writing. Before that, he worked at a variety of Boston area bookstores.

He seems anxious to leave. Gesturing to a supine figure in his fully-reclined passenger seat, he explains that he has to drive the guy to the Shell station to work a graveyard shift, after ten hours painting Scarbrough’s store.

Scarborough climbs in the car and leaves, promising to take me with him on a book-buy- ing run to Roxbury, where he says he got in a fight with somebody a few weeks ago who was trying to rob him (“That’s where bookselling gets interesting”). It sounds fantastic to me and he assures me that we’ll coordinate over email.

I haven’t seen him since. Follow-up emails, so far, have been ignored.

I’m inexplicably disappointed by this. I still stop by the stall every now and then.