UPDATED: April 9, 2014, at 1:54 a.m.

Four months after his arrest for allegedly engineering a bomb hoax on Harvard’s campus, Quincy House sophomore Eldo Kim has still yet to be indicted by a grand jury.

Allison D. Burroughs, Kim’s private counsel, declined to comment on the proceedings of the case, which began with a federal complaint on Dec. 17, 2013 alleging that Kim sent several emails saying he had placed bombs in two campus buildings. The U.S. Attorney’s Office did not respond to multiple requests for comment, and the case’s electronic court record has not changed since Dec. 23.

The Speedy Trial Act of 1974 mandates that a suspect be indicted within 30 days of arrest.

Yet, according to legal experts, a variety of pretrial delays can extend that timeframe, sometimes to a great extent.

Alex Whiting, a professor of the practice of criminal prosecution at Harvard Law School, said that the defense and the U.S. Attorney’s office may be working to settle the case without a trial.

“If a trial has not reached a grand jury, that suggests that there are discussions between the defense and the prosecution about a resolution of the case, which I would expect anyhow,” Whiting said. “Those discussions may result in resolution, or they may not, but it’s no surprise that there would be ongoing discussions.”

However, Jeffrey A. Denner, founder of the Massachusetts firm J A Denner Criminal Defense Group, cautioned that the arrest was recent enough that no conclusion can be drawn from the delay.

“I do not know whether negotiations are going on,” Denner said. “Normally the defense lawyer and the U.S. attorney talk. Talking doesn’t mean they’re negotiating.”

Denner also pointed out that the delay may be caused by the U.S. Attorney’s need to gather more evidence, rather than by negotiations.

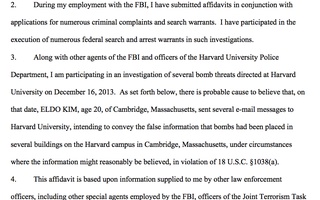

According to an affidavit filed by an FBI agent in December, Kim confessed to making the Dec. 16 bomb threat—which was sent to the Harvard University Police Department, University administrators, and the president of The Crimson—to avoid a final examination.

“Normally, it’s not the defendant that’s slowing the indictment process down, it’s the U.S. Attorney’s office,” Denner said.

Like Whiting, Kari E. Hong, an assistant professor at Boston College Law School and a criminal appeals attorney, said that she suspects the defendant’s counsel is in negotiation with the prosecution.

“A good criminal defense trial attorney will be on the phone with the prosecutor on day one, trying to negotiate,” she said. “Over 95 percent of cases are resolved by plea, so the earlier that happens, the better. I tell my students, the very best defense attorney is someone who is on very good terms with the prosecution.”

If convicted under the federal bomb hoax statute, Kim could be sentenced to up to five years of imprisonment, three years of probationary release, and a $250,000 fine.

Still, Whiting said that a variety of reasons could motivate the U.S. Attorney’s Office to negotiate a lesser penalty.

“I would expect the office to take into account all the different factors—the effect on the community, the resources that were diverted as a result of the event—but also all the particular circumstances of the defendant: his motivations, whatever they can learn about his psychological state at the time, and whatever circumstances he found himself in,” Whiting said.

Kim’s alleged threats led to a lockdown of the four campus buildings mentioned in the threat and restriction of access to Harvard Yard. University, local, state, and federal law enforcement personnel searched for five hours before ultimately determining the threat was not credible.

The University has previously said it will not comment on the criminal proceedings. According to Kim’s former roommate at Harvard, Daniel P. Leichus ’16, Kim returned to campus within the first week of his arrest to claim his belongings. In December, a federal judge mandated that Kim remain in Massachusetts pending trial.

—Staff writer Daniel R. Levine can be reached at daniel.levine@thecrimson.com. Follow him on Twitter @danielrlevine.

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

CORRECTION: April 9, 2014

An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified the legal expert who suggested that the U.S. Attorney’s office may be trying to settle the case without a trial. In fact, it was Alex Whiting, a professor of the practice of criminal prosecution at Harvard Law School.

Read more in College News

Humble and Faithful, Andrew Sun ’16 Was Quick to Listen, Friends SayRecommended Articles

-

Freshmen Leave for New Haven.The Freshman nine will leave Harvard square this afternoon at 2 o'clock to go to New Haven. Following are the

-

Cohen Discusses The Power of FilmThough it would be going too far to suggest that director Rebecca Richman Cohen HLS ’07 aestheticizes tragedy, one thing is immediately clear: CSPAN this is not.

-

Protecting the Dignity of Discourse on CampusToo often, we forget that freedom of speech is largely about silence. The dignity of discourse in America stems not merely from the right of each individual to speak freely, but from those who might vehemently disagree making space for that person to express themselves.

-

Motion to Dismiss Charges Denied in Brittany Smith CaseA judge has denied Brittany J. Smith’s motion to dismiss charges for her involvement in the May 2009 shooting in Kirkland House.

-

Change of Plea Hearing Scheduled for Brittany Smith

Change of Plea Hearing Scheduled for Brittany Smith -

Eldo Kim ’16 Will Face Uphill Battle in Court, Dershowitz, Experts Say

Eldo Kim ’16 Will Face Uphill Battle in Court, Dershowitz, Experts Say