When the Wicked Witch of the West and her evil winged monkeys appeared on screen in “The Wizard of Oz,” A.O. Scott ’87-’88 ran out of the room screaming.

While he was only three at the time, his mother Joan W. Scott, who received an honorary degree from Harvard in 2007, explained that her son’s reaction is not exactly what you would expect from the future chief film critic for the New York Times.

From a very young age, his mother said, Scott had won writing competitions held by English teachers and children’s magazines. Although it was always clear that he had wanted to be a writer of some kind, his foray into a professional career in writing did not begin with films.

At Harvard, in fact, when Scott was not at home in the Dudley Co-op or waiting tables at Café Pamplona, he spent most of his time with books.

Scott, who graduated magna cum laude with a degree in literature, found that his time on campus influenced his career in many indirect ways, whether it was through his conversations with friends, attendance at local movie screenings, or focus on his coursework.

Michael Katz ’87, a close friend of Scott’s from college, remembered Scott’s passion for literature. He loved reading stories, and he loved telling them.

“He could sit at a manual typewriter and type an entire essay for whatever essay he was doing from beginning to end,” Katz said. “You could count the number of times on a hand that he would backspace.”

Katz said that the group of friends spent most of their time at Harvard discussing a range of topics, from poetry to books to movies.

“Whatever it was—it could have been a Latin American novel that Carlos Fuentes was teaching at the school at the time, or it could have been anything—he would just have a blast talking and thinking about it,” Katz said.

Justine H. Henning ’88, now Scott’s wife, also stressed Scott’s genuine interest in his studies. The two first met while attending to some of the Co-op’s chores: He had signed up to wash the pots, while she had signed up to wash the dishes.

“He was part of the cigarette smoking crowd of the Co-op, and I was more of the vegetarian, hippie crowd,” Henning said. “It was a little bit like Romeo and Juliet.”

Scott’s intellectual nature was something that Henning found charming.

“He took academics very seriously, which he still does. He reads absolutely everything,” Henning said. “He has this impressive breadth of knowledge which has served him really well.”

One of her fondest memories of Scott from their college days involved a trip to the library together. When she and Scott first began dating, he offered to walk her to Hilles Library, carrying her books for her as they walked.

“It’s so old-fashioned, and I was really touched by that,” Henning said.

Although Scott said there was a lull in the movie scene on campus during his time as a student, he still found time to watch films when he was not studying, making it to the movies three or four times every week. Scott also remembered partaking in some of Harvard’s movie traditions, like watching “Casablanca” at the Brattle Theatre or watching “Love Story” during Opening Days as a freshman. “I got a pretty good movie education from the Brattle Theatre, different house film societies, and the Orson Welles Theatre,” he said.

Still, Scott’s education did not directly translate to a clear future career path. Henning cited Scott’s further ties to academia, noting that both of his parents are professors. “It was almost in his genes to do that,” she said.

After graduating, Scott spent a few years in a graduate program in literature at Johns Hopkins University before deciding to write book reviews for The Nation.

From there, he went on to the New York Review of Books and eventually worked as a book critic for Newsday and as a contributor to Slate magazine. When the New York Times read a piece he wrote on Martin Scorsese in 1999, they had discovered their next chief film critic.

“Writing careers are often a series of accidents or lucky breaks or decisions that someone else has made,” Scott said. “That I write about movies for a living happened by accident.”

Despite this, Katz said that even as a college student, Scott exhibited some characteristics of his future role as a critic.

“He’s a natural-born critic in the true sense of the word: He is an appreciator of things and likes to digest them and think about them and think about what it means in the world,” Katz said. “Although I never identified him with film in any way, I can see why he became a critic.”

The intellectual environment that Harvard and his friends provided helped Scott build the skills he would later need for a career in criticism.

“In a general way, what I learned as an undergraduate was kind of how to be serious and how to take pleasure in being serious,” said Scott. “More than any particular subject I learned in a class, it was that atmosphere of intellectual intensity and curiosity that helped me.”

This passion for literature and film still lives in the Scott family today. Scott is currently working on a few book projects of his own, and Henning has been involved in teaching and tutoring.

Their children, Ezra, 16, and Carmen, 14, have already been bitten by the performing and film-making bugs, according to Scott’s mother. Carmen has played lead roles in school theater productions, like Juliet in “Romeo and Juliet,” while Ezra, on the other hand, has taken a behind-the-scenes approach, aspiring to be a filmmaker.

Twenty-five years later and a new career path aside, his friends conclude that the intellectually driven Scott has not changed all too much.

“Tony to me is still the Tony he was when we hung out in college...except now he sees a lot more movies,” Katz said.

—Staff writer Cynthia W. Shih can be reached at cshih@college.harvard.edu. Follow her on Twitter at @CShih7.

Read more in News

Stephanie D. WilsonRecommended Articles

-

HDC to Miss Annual Yale Drama FestivalThe University will not participate in the Yale Drama Festival this year, Joel F. Henning '61, president of the Harvard

-

Summer Group Plans Four Shows in LoebLoeb Drama Center's summer company will present plays by Shakespeare, Anouilh, Shaw and Brecht in an eight-week season starting June

-

Anchors AwayE ARLIER THIS MONTH, WNEV-TV, channel 7 in Boston began featuring a new anchor team on its 6 p.m. and

-

Harvard Drama Takes to a New Stage

Harvard Drama Takes to a New Stage -

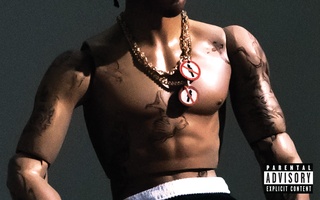

Travis Scott Energetic but Scattered in Debut Album

Travis Scott Energetic but Scattered in Debut Album