In 1986, as the Cold War neared its end, Harvard featured a Soviet prison camp of its own.

The Conservative club had built a gulag camp in the Yard that remained standing throughout the academic year, protesting human rights abuses in the U.S.S.R., recalled Charlene H. Li ’88.

According to Li, who likened the protests to those of the recent Occupy movement, students adhered to a schedule to ensure that the encampment was constantly occupied so that University officials would not tear it down.

Harvard’s lone gulag marked a tangible link between Harvard students and the Cold War, the decades-long standoff that separated the United States and its NATO allies from the Soviet Union and its satellite nations in Eastern and Central Europe. This connection was otherwise often lost on students focused on daily campus life.

“People were preoccupied with more mundane things, like ‘How am I going to do on my Ec10 exam?’ and ‘Who am I going to meet on Friday night?’” said Scott W. Horsley ’88. “It was probably the same thing in Moscow or East Berlin.”

Nevertheless, the tense political atmosphere of the epoch permeated campus, making its influence felt in numerous aspects of University life.

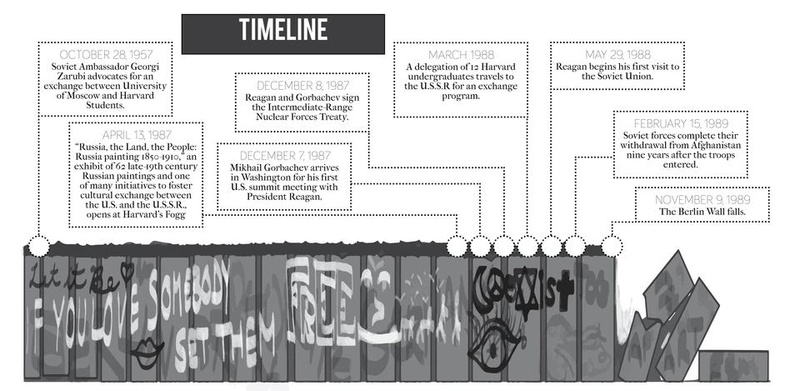

As an academic institution, Harvard played an important role in fostering cross-cultural awareness and dialogue between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R.

A SPACE FOR DISSIDENCE

The University was home to a number of émigré professors, who had fled the Soviet takeover of Eastern Europe for a place to voice their opinions openly.

One of these was social sciences professor Liah Greenfeld, who had fled the U.S.S.R. with her family when she was 17. For intellectuals like herself, “the [Soviet] lack of freedom was unbearable,” she said.

These professors often published perspectives critical of the Soviet Union, as they “had strong commitments to individual rights and liberties and strong indictment of the totalitarian or Soviet system of government,” said Frank E. Sysyn, who taught Soviet and East European studies on campus between 1976 and 1988.

Featuring voices like Greenfeld’s, the many research contributions to Russian and European Slavic studies that Harvard’s Russian Research Center and Ukrainian Institute facilitated were not always appreciated on both ends of the spectrum.

“The soviet Union did not like the attention [Harvard] paid to dissidence within the Soviet Union, to the striving of European peoples to autonomy, and to various Eastern European cultures,” Sysyn said.

As a result, he said, many Harvard students researching Soviet countries were frequently denied access to important works.

Sysyn said he thought that this censorship made work in this area more attractive to students, who were already interested in studying the Soviet system.

Read more in News

On the Losing Team: Harvard Plays for Dukakis in 1988 ElectionRecommended Articles

-

The ‘Wall’ in their Own WordsA generation of post-Soviet literary figures write essays and fiction on life in the Bloc

-

Illusions in the MotherlandAs the host of the 2014 Winter Olympics, Russia will find it difficult to close the door on the glimpse Vancouver has provided of a fake superpower with an ego problem.

-

Estonian President Addresses Kennedy SchoolPresident of Estonia Toomas H. Ilves discussed the relationships between the EU and NATO, and between Estonia and the Soviet Union yesterday at the Harvard Kennedy School.

-

Bezmozgis Offers Uninspired Take on Immigrant ExperienceFor a few decades in the middle of the last century, American fiction featured a strong Jewish voice, world-weary yet wisecracking, in which unconcern—even disgust—toward the world coexisted with fascination with its linguistic and philosophical possibilities. With his existential emphasis, the Jew became the everyman; though the Jewish immigrant now rarely appears as a novelistic protagonist, a great nostalgia for his brand of schmerz persists.

-

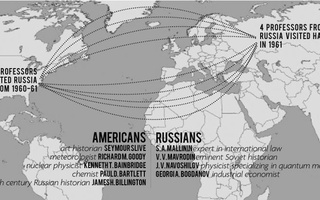

Despite Tensions, Professors Cross Iron Curtain

Despite Tensions, Professors Cross Iron Curtain -

Mitt Romney’s RussiaRomney appears to cling to the implicit assumption that a post-Soviet Russia still poses the gravest danger to American interests.