On a cloudy Saturday afternoon in October 1962, fearful students filled the bleachers of Soldiers Field to watch a game against Dartmouth that could have meant the Ivy League title for the Crimson. But the students’ fear was not just for the College’s football legacy.

“I looked around [the stadium] and thought, ‘Gee this is scary,’ I wondered if we would have another game,’” Charles A. Stevenson ’63 said.

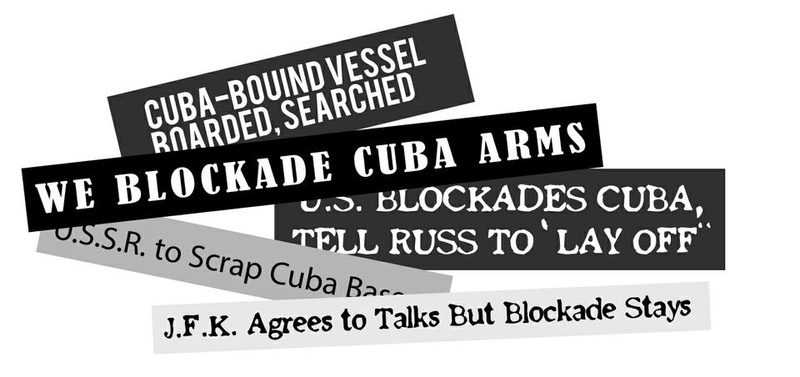

Six days earlier, President John F. Kennedy announced the presence of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba in an address to the nation. On the brink of nuclear war, students huddled together in common rooms and voiced concern at faculty-led discussions. A few left campus all-together, some wrote in journals. Most had faith in Kennedy, “the Harvard guy next door,” and others criticized his stance as too aggressive.

Students, however, reflect now that they did not know just how close the world had come to nuclear war.

MIXED FEELINGS

On Monday, October 22, 1962, students crowded around television sets to watch Kennedy’s speech on the situation, where he outlined initial steps to be taken, including a quarantine against Cuba.

“We will not prematurely or unnecessarily risk the costs of worldwide nuclear war in which even the fruits of victory would be ashes in our mouth but neither will we shrink from that risk at any time it must be faced,” Kennedy said that night, leaving the nation wary of what could become of the crisis.

“There was a sense of unreality,” said Kenneth L. Freed ’63, who remembered watching the speech in a common room of Quincy House.

While previous generations had witnessed two world wars, students at the College had not been exposed to the reality of global warfare; American soldiers were positioned in Vietnam but had yet to engage in combat.

“It opened up a huge amount of conflict in American society. It shattered the basically calm and not-so-bad 50s environment in which we grew up,” Freed said.

Later that night, another student recalled the loud playing of Mozart’s Requiem as a group drank and contemplated Kennedy’s address before returning to their studies. Others were too intrigued that night to focus on their academics, like Stevenson, who wrote in his college journal: “Heard excellent Kennedy speech—I hope for the best.”

Todd A. Gitlin ’63, former president of Harvard’s anti-nuclear group, Tocsin, who would go on to serve as president of Students for a Democratic Society, said that some students were so agitated that they even left campus.

“People were getting into cars, leaving town, and going to Canada. People were critically upset about what was happening. It really did seem there was a live possibility of nuclear war,” Gitlin said.

OPENING DISCUSSION

Those who remained on campus witnessed student and faculty discussions on the issues at the hand.

Read more in News

At 'Cliffe And Graduate Schools, First Female Grads Blazed TrailsRecommended Articles

-

College Political Clubs Join in Fund DriveThe University's eight undergraduate political organizations have started a combined fund-raising drive to provide themselves with common secretarial services and

-

Tocsin News ForumHappily, this month's Tocsin News Forum shuns the strident, there's no time, brother tone which undergraduate writers on Berlin and

-

Students and Faculty Fight Nuclear TestsIn the spring of 1960, 1,359 members of the Harvard faculty signed a petition encouraging the Eisenhower administration to consider ...

-

Ted Kennedy '54-'56 Went To The Senate In 1962, But Not With Harvard's Support

Ted Kennedy '54-'56 Went To The Senate In 1962, But Not With Harvard's Support -

Harvard and the Atomic Bomb

Harvard and the Atomic Bomb