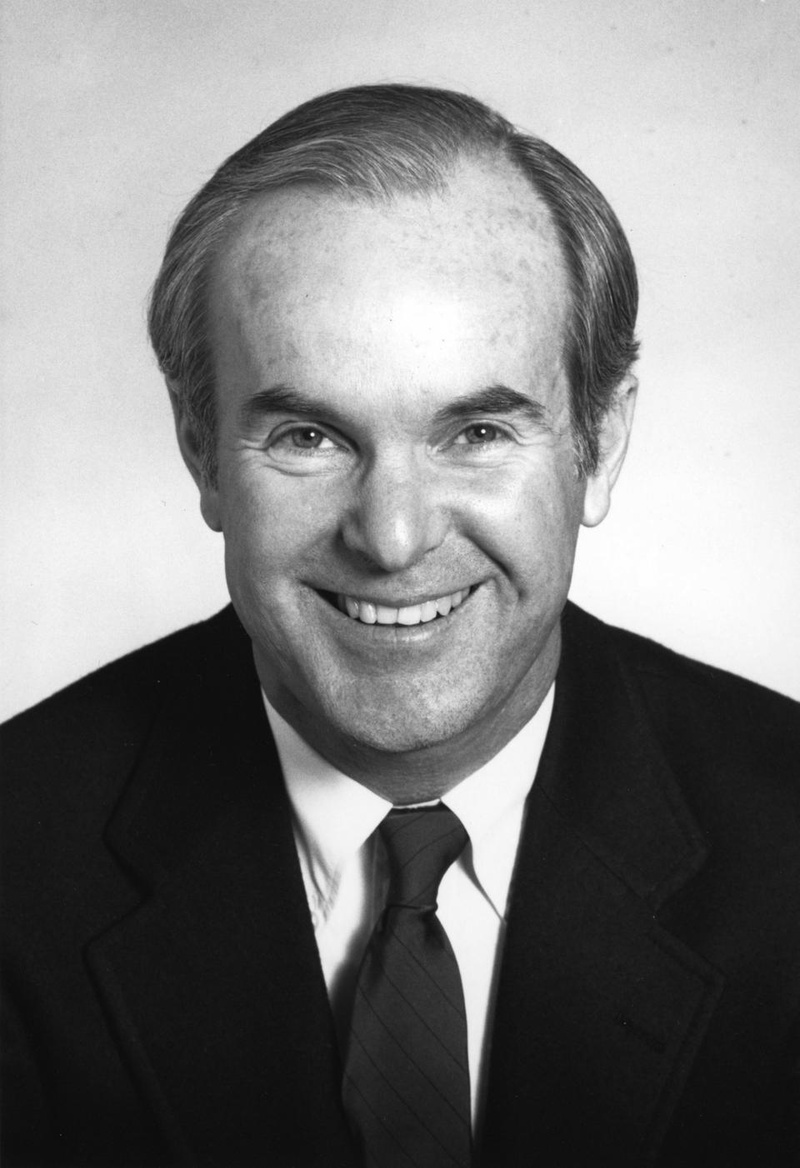

When the late Washington governor Booth Gardner, a member of the Harvard Business School Class of 1963, reached his senior year at the University of Washington in 1958, Harvard Business School was not even on his radar.

As biographer John C. Hughes wrote in “Booth Who?”, the idea of applying to the Business School only occurred to Gardner after a snowstorm and a planning mishap made him the unofficial escort of former Harvard Business School Associate Dean J. Leslie Rollins when Rollins came to meet Business School prospective students at the University of Washington.

Hughes wrote that Rollins was immediately “impressed” with Gardner and encouraged him to apply.

Gardner ultimately matriculated to the Business School in the fall of 1961. There, he honed skills that—as several of Gardner’s political advisors told The Crimson—would be invaluable in his career in government. The former governor, who passed away this March, ran the state of Washington with a personal and compassionate management style, fighting for his beliefs until the end.

‘THE MOST MODEST MAN’

Gardner was born in Tacoma, Washington, in 1936. After attending the University of Washington and the Business School, he began a career in politics that ultimately coalesced in his successful election to the Washington governorship, where he served from 1985 to 1993.

Giving rise to the campaign motto “Booth Who?” when Gardner first ran for the governor in 1983, he was a little-known county executive in an election contest with the Republican incumbent John Spellman.

Gardner claimed to offer business acumen and managerial expertise to the people of Washington.

“Harvard—people can see that as snob appeal,” said political consultant Ron Dotzauer, who served as Gardner’s campaign manager. “But I used the Harvard Business degree to say ‘Who do you want to run your state?’”

Dotzauer ran a campaign ad that compared the two candidates’ resumes side-by-side.

“Booth didn’t have [HBS] emblazoned on his chest,” Dotzauer said. “But that was part of his resume that we ran on.”

Gardner also had worked at the Business School to work as an assistant to the dean in1966 before returning to Washington.

Speaking on the influence of the Business School on Gardner’s administrative style, Congressman Dennis Heck, who had served as Gardner’s as chief of staff, said, “The way he worked was to hire very good people, let them do their job, focus on a limited number of priorities...I’ve always assumed that part of that was Harvard.”

But after his campaign for the 1984 election, Gardner—like many politicians with Harvard degrees—downplayed his association with the University before the public. According to Heck, Gardner’s quietness about his Harvard experience stemmed not from political maneuvering but

rather from a deep-seeded humility.

Gardner was the stepson of the wealthy businessman Norton Clapp and as such the heir to the family fortune. But Heck described Gardner as a “most modest man” who had “the common touch” despite his wealth.

Throughout his political career, Gardner showed particular concern for the needs of the poor. In the late 1980s, Gardner signed into law “Basic Health,” a state-sponsored program that through private health plans would provide low-cost health care for the working poor.

“Here’s a man who could have lived a life of luxury, but he was always completely engaged in what was happening in the world and always put service above self,” said Ronald Erickson, a Washington-native who has served as a senior executive for several Washington-based companies.

A MBA AND A MBWA

Gardner’s political advisors agreed that sociability was one of his greatest attributes, allowing him to connect with his constituents, his political allies, and his political foes alike.

As Hughes wrote in “Booth Who?”, Gardner often said that more valuable than any MBA was his “MBWA,” his philosophy of managing by walking around.

Dia Armenta, who served as Gardner’s political strategist, said that despite having eaten out with the Gardner on dozens of occasions, she could not recall ever walking straight with the Governor from the entrance of a restaurant to their table. The Go

vernor instead would head to kitchen and talk to the staff and waitresses.

Armenta said that years after the Governor’s tenure ended, Gardner would visit the capitol offices and chat with the receptionists and other clerical workers who had served under his administration as well.

“He wanted to know how their families were doing. He remembered their names,” Armenta said.

As Dotzauer said, with a natural friendliness and a good memory for names, Gardner was adept at campaigning. But Dotzauer noted that, ironically, Gardner abhorred the campaign trail.

“When he first ran for governor in 1983, he’d say Ron, ‘I just wish I could apply for this job. I’d be hired,’” Dotzauer said. Laughing, he added, “This is what you’d expect from a Harvard MBA.”

CAMPAIGNING TILL THE END

By the time Gardner left the governorship in 1993, Washington was a leader in the realms of health services and environmental management. Gardner had also been a champion of equality.

In a move that Heck called “ahead of the times,” Gardner had also issued an executive order, banning discrimination against gay and lesbian state workers.

After doctors diagnosed him with Parkinson’s disease in 1994, Gardner was inspired to re-enter public life to launch what he said would his last campaign—to legalize physician-assisted suicide—stemming from Gardner’s desire to control his own time of death and to avoid prolonged suffering.

But to increase its chance at passage, Gardner changed the legislation to mirror the Oregon law on physician-assisted suicide, which restricted it to terminally-ill patients.

Gardner’s last campaign proved to be a success, and Washington voters approved his proposal in 2008. But Gardner did not stand to benefit from the legislation he championed.

Director Daniel Junge created a documentary entitled “The Last Campaign of Governor Booth Gardner,” which followed Gardner’s campaign for physician-assisted suicide.

“I think it’s just remarkable that here’s a guy at the end of his life when he should be sitting back...but he chose such a contentious issue to put the political capital he had in,” Junge said. “It just speaks to his passion for civil service.”

At Gardner’s memorial service this spring, President of the University of Puget Sound Ron R. Thomas spoke of the “indelible” mark he left on Washington politics.

Alluding to Gardner’s infamous political slogan, Thomas said, “There is now, almost no one, who doesn’t know who Booth was.”

—Staff Writer Sonali Y. Salgado can be reached at ssalgado@college.harvard.edu. Follow her on Twitter @SonaliSalgado16.

Read more in News

Janet Reno, J.D. '63, And Her Long Path From Cambridge to The CapitolRecommended Articles

-

SAT Prep Aims To Level the FieldFounded by two Harvard alumni, the newly-formed Ivy Key SAT preparation company may seem a bit exclusive at first glance.

-

Gardner '65 Calls For Education in in EthicsChanneling the ideas of his newly-released book, Graduate School of Education professor Howard E. Gardner ’65 stressed that modern education must incorporate “truth, beauty, and goodness.”

-

The Fall of Academics at Harvard

The Fall of Academics at Harvard -

A Dark Weekend for the 'Party Shuttle'

A Dark Weekend for the 'Party Shuttle' -

After Administrative Review, Party Shuttle Returns, Subdued

After Administrative Review, Party Shuttle Returns, Subdued -

Psychologists Talk About Minds and ResearchMore than a hundred students and community members packed Geological Lecture Hall Tuesday evening to listen to a conversation between psychology professors Steven Pinker and Howard E. Gardner ’65.