President John F. Kennedy '40 photographed in Boston by The Crimson on Saturday, October 19, 1963, just a month before he was assassinated. The photograph ran on page two of the Saturday, November 23, 1963, issue of The Crimson.

In living rooms and on front porches across the nation, from Harvard Yard to Dallas, groups formed around televisions and radios to hear the impossible. Elsewhere, citizens young and old were moved to tears, privately mourning a public loss.

The assassination of President John F. Kennedy ’40 on November 22, 1963, holds a unique claim on the American psyche. It was perhaps one of the first and most powerful instances of the live news media shaping the national experience. And yet, to those who experienced it, Kennedy’s death was also intensely personal in a way few events in American history have been.

Fifty years later, those personal memories are what remain. The Crimson has asked a broad range of alumni, many of whom are still a part of the Harvard community, to reflect on the moment they heard of the President’s death. A smaller number of experts around Harvard have offered an assessment of Kennedy’s legacy in American culture and political history.

A number of those remembrances are printed here.

***

The day President Kennedy was shot in Dallas, I remember walking down Dunster Street around noon toward Eliot House, where I was a tutor in English. I was going to the Senior Common Room before heading to lunch in the dining hall. I remember seeing two young men throwing a frisbee and one shouted something about the president being shot. They nonchalantly continued throwing the frisbee.

When I got to Eliot House, the news that the President had been shot was confirmed and we headed down to a basement recreation room to watch a TV set with Walter Cronkite announcing in solemn tones that the President had been shot. Soon his death was reported, and we all were in a state of shock and disbelief that this had happened. After all, President Kennedy was a Harvard man and, in the words of Joseph Conrad, he was "one of us."

The following days were a period of uncertainty and mourning for the Harvard community.

Michael Shinagel, senior lecturer in English and Dean of the Division of Continuing Education Emeritus, was a Ph.D. candidate at Harvard in the fall of 1963.

***

November 22, 1963, was a warm, late fall Indian summer day. My fiancé, John Clark ’64, and I were walking around Harvard Square in the early afternoon after lunch. It was the day after my 21st birthday and my parents were going to meet us later for a performance of "The Caucasian Chalk Circle" by Bertolt Brecht at the Loeb Theater in the evening.

We were walking on Mass. Ave. just along the Yard. At some point we became aware of a kind of quiet and then heard radios through open windows from the freshman dorms. I think we heard the news of Kennedy being shot that way.

We never did see the play. I think we took the train to my parents house in Canton and then spent the weekend glued to the TV, which belonged to my grandparents who were living with us....

We were stunned. Just stunned. After we graduated we joined the Peace Corps, which of course was Kennedy’s idea, and went to Turkey. The Peace Corps was then headed by Sargent Shriver, Kennedy's brother-in-law.

Colleen Gaines Clark ’64 was a Radcliffe senior when the president was assassinated.

***

I remember crossing from the MBTA island [in Harvard Square] to the corner of Mass. Ave. and Boylston. A young woman crossing the other way was openly sobbing. I wondered what that was about. I went to my room in Kirkland, and as I was turning on the radio, I heard someone in the courtyard say “Kennedy has been shot.”

As the radio came on, “the President is dead” boomed out. For some reason I went up to the Yard and stood there as people listened to transistor radios. The sky was bright blue, but somehow it seemed black.

John Clark ’64, Colleen Gaines Clark’s husband, was a senior at the College in the fall of 1963.

***

At half-time in the middle of the afternoon of November 22, 1963, in New Haven our soccer game against Yale was deadlocked at 1-to-1. In those days this always took place on the Friday afternoon before The Game. Our team was in a huddle just before taking the field when our captain, my roommate Lou Williams, brought the dreadful news from the sidelines: “President Kennedy has been shot. He's dying.” So engrossed in the game were both teams as well as our coaches and any "officialdom" that may have been in attendance that the shock failed to distract us, and we finished the game.

Today, I have a glossy framed newspaper photograph in my study. Four people are frozen in time. My teammate Chris Ohiri (dead of cancer two years later and in whose memory Ohiri Field now hosts Harvard's home soccer games), his profile a picture of rapture, has just kicked the winning goal. I am next to Chris, back to the camera doing nothing very useful. Ditto the Yale goalie. The entire dramatic value in the picture is produced by the ashen, distant stare on the face of the single remaining spectator standing directly behind the Yale goal, alone in his misery and utterly oblivious to what was going on in front of him. One of the Yale substitutes was John Kerry. Michael Crichton was the soccer-reporting Crimson scribe.

John Thorndike ’64, was a senior in the Fall of 1963. He graduated from Harvard Law School in 1968.

***

What I recall is that [Managing Editor Bruce Paisner] and I and others were in the newsroom in early afternoon when the first calls came in, from students on campus who'd heard the news on the radio and wanted us to confirm. Within a half hour we'd rented a TV and set it up in the newsroom; remember, this was before TVs were ubiquitous and decades before the Internet, so we were depending on the TV networks and our clanky AP teletype machine, our one link to the world of (almost) real-time news. Bruce quickly handed out the assignments; mine, as Associate Managing Editor was to man the desk, edit copy and make sure everything was as concise and accurate as the immense time pressure and the many gaps in information allowed.

Beyond the obvious Harvard connection of a U.S. President who was an alumnus and an Overseer and who had brought many Cambridge luminaries (Bundy, Galbraith, Schlesinger and others) to the White House, there was the immediate matter of The Game, scheduled for the next day, Saturday.... I believe some of the Harvard House-Yale College football games were already in progress when the news was confirmed; some or all may have been cancelled mid game. Within hours The Game itself was cancelled.

Without the task at hand, of reporting, editing, and putting out the Extra, many of us would have dissolved into tears but we kept it together because this was by far the most important story we would ever handle on The Crimson, and one of the most important The Crimson has covered in its long history. No one alive that day will ever forget it, and especially not those of us on The Crimson who had the special responsibility of recording history.

Efrem Sigel '64 was Associate Managing Editor of The Harvard Crimson in the fall of 1963.

***

As I was walking back to Leverett House from having a haircut and passing through Harvard Yard, the Yard was strangely quiet—only the tolling of the Memorial Church bell; not ringing, but slowly tolling. There were quiet gatherings in the entryways to a number of the buildings. I approached one to ask what was going on, and was told that the President had been shot. We went from the fall of our freshman year, when Jack Kennedy was elected, to the fall of our senior year when he was taken from us. Some of our classmates joined the Peace Corps; some went to Vietnam; many went on graduate school. But none of us forgot that awful moment.

Thomas Brome ’64 was a senior in the fall of 1963.

***

Like so many other Americans, I do remember where I was on the day John F. Kennedy was assassinated. I was in the dining room of Eliot House (where I was a tutor) near the second window on the left as you enter. Somebody heard the news that he was shot on a transistor radio, and our group sat stunned at the enormity of the crime. Our first thought was dismay that his successor would be Lyndon Johnson—a man who turned out to be an abler President and a more effective liberal than Kennedy.

President Kennedy’s assassin was at first thought to be a right-wing bigot, but Lee Harvey Oswald was in fact a self-described Marxist and an admirer of the Cuban Communist tyrant, Fidel Castro. This was difficult for most liberals—and thus most of Harvard—to accept because Dallas had indeed been a center of right-wing bigotry. Still today much of the country believes there is something sinister about Dallas and that Kennedy was the victim of conspiracy, despite overwhelming evidence that Oswald by himself was the killer. It is disturbing to think that a man so highly placed and so attractive as Kennedy could be so vulnerable as to be brought down by a sample of the dregs of humanity. Aside from the attitude of liberals, our democratic spirit shudders to think that the people in which we take pride could contain an Oswald.

Harvey C. Mansfield ’53, a government professor at Harvard, was a lecturer at Harvard in the fall of 1963.

***

I will never forget the moment I learned of the tragedy in Dallas. I was coming out of a French class in Boylston Hall and everyone was huddled around a radio on the steps when someone said: “The President has been shot.” Students and teachers were in tears; some retreated to quieter places; others stared into the afternoon sky in disbelief.

It was such a hopeful time. The President had spoken to a crowd in front of the Berlin Wall in June claiming “Freedom is indivisible, and when one man is enslaved, no man is free” and, in the same month, had championed the cause of civil rights at home, stating that “every American should enjoy the privileges of being American without regard to his race or his color.” Our leadership was young, visionary, resolute, and inspiring. And, suddenly, we were threatened by an unknown assailant and the uncertainty that the progress we’d counted on as a country and as a globe we would ever get to see.

The Harvard-Yale game the next day was postponed—a fitting response to the tragedy and the beginning of a period of mourning on the campus, the likes of which we would not see again until that fateful day in September, 2001.

Thomas A. Dingman ’67, the Dean of Freshmen, was a himself freshman at the College when the President was assassinated.

***

Most if not all 1964 classmates recall exactly where they were when they heard that Kennedy had been shot. We were the only class whose Harvard years began before the 1960 election, and ended the year after Kennedy was assassinated. And we were certainly a class full of members inspired by his words and expressed idealism (and, to be sure, affected on the negative side by his expansion of the war in Vietnam).

I had an 8-inch vertical screen TV (cathode ray tube of course, with vacuum tubes), housed in a big wooden box that took up half my desk, and all of Kirkland House Annex D-entry was glued to that TV for the rest of the day. Others sought TVs wherever they could be found.

John H. Henn ’64 is Secretary for the Class of 1964.

***

In an age of hyper-partisanship, John F. Kennedy’s legacy continues to inspire not just Democrats and those on the left, but also those on the right. Witness the recent book by my classmate and former Crimson president Ira Stoll ’94, “JFK, Conservative” Despite being born almost ten years after his death, he certainly inspired me.

While growing up, my two favorite Presidents were Ronald Reagan and John F. Kennedy. JFK was young and cool, and his wife was elegant. He was a war hero, a big believer in our country and an inspirational speaker who challenged Americans to act upon our dreams.

As an incoming Harvard freshman, I became ecstatic upon being assigned to Weld Hall, the President’s freshman dorm. My roommates and I called our room “The Kennedy Suite” and covered its walls with JFK posters purchased at the Coop.

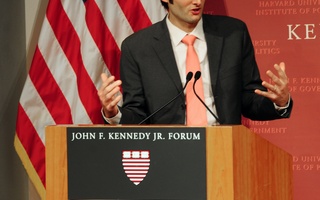

Twenty years later, I am now at the helm of the IOP, a living memorial to President Kennedy, where for almost fifty years, we have celebrated the President’s legacy every day. Watch the IOP’s #EveryDayJFK video—our hope is that the attention paid to President Kennedy on this anniversary will inspire a new generation of Americans to heed his call to public service.

C.M. Trey Grayson ’94 is the director of the Institute of Politics.

***

For people alive at the time, Kennedy’s assassination was one of those events so shocking that you remember where you were when you heard the news. I was getting off a train in Nairobi when I saw the dramatic headline. Though his life had been plagued by illness, Kennedy projected an image of youth and vigor that added to the drama and poignancy of his death.

How might history have been different if he had survived? In my recent book, Presidential Leadership and the Creation of the American Era, I divide presidents into those who are transformational in their objectives, pursuing large visions related to major changes; and those who are transactional, more focused on pragmatic issues of making the metaphorical trains run on time, and keeping them on the tracks. Because he was an activist and a great communicator with an inspirational style, Kennedy appeared to be a transformational president. He campaigned in 1960 on a promise to “get the country moving again.”

Kennedy’s inaugural address appealed to sacrifice and asking not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country. He instituted programs like the Peace Corps, a manned landing on the moon, and an Alliance for Progress with Latin America. But despite his activism and rhetoric, Kennedy was a cautious rather than an ideological personality. In the words of the presidential historian Fred Greenstein, “in fact Kennedy had little in the way of an overarching perspective.”

Rather than being critical of Kennedy for not living up to his rhetoric, we should be grateful that in critical situations, he was prudent and transactional rather than ideological and transformational. The most important thing that Kennedy did during his brief presidency was to manage the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis and avoid what was probably the highest risk of nuclear war in the last century. Kennedy learned from his failures at the Bay of Pigs and created a careful process for managing the crisis that arose after the Soviet Union placed nuclear weapons in Cuba. While many of his advisors, including the military, urged an air strike and invasion which we now know might have led Soviet field commanders to use their tactical nuclear weapons, Kennedy played for time and kept options open as he negotiated a stand-down with Nikita Khrushchev. What is more, Kennedy learned from the near miss of the Cuban Missile Crisis and on June 10, 1963, he gave a speech that began the process of easing the tensions of the Cold War. In his words, “I speak of peace, therefore, as the rational end of rational men.” While a presidential vision of peace was not new, Kennedy followed it up by negotiating the first nuclear arms control agreement, the Limited Test Ban Treaty.

The great unanswerable question of his presidency is whether he would have saved us from the folly of the Vietnam War. Historians have argued both sides of that question, but we shall never know because his promise was sadly cut short. And that was a great loss.

Joseph S. Nye, University Distinguished Service Professor and former dean of the Harvard Kennedy School, was a Harvard Ph.D. candidate in government in the fall of 1963.

***

John F. Kennedy spent his short life in public service as a decorated naval officer, a member of the U.S. House and Senate, and then, at 43, as our youngest elected President. He issued a call in his inaugural address for all Americans to serve others and to ask what they could do for their country.

Charismatic and telegenic, he stumbled badly at the outset of his presidency when he approved a plan to invade Castro’s Cuba at the Bay of Pigs, then was sobered by his meeting with the Soviet premier, Nikita Khrushchev, in Vienna and by the erection of the Berlin Wall.

At the height of the Cold War, his image—young, vibrant, handsome, articulate—contrasted sharply with his Soviet counterpart and boosted America’s standing abroad.

His enthusiasm for space exploration reflected the American desire to accomplish ambitious goals and to explore the next frontier. His steady, resolute, creative decision making in the Cuban missile crisis averted war and gave Americans renewed confidence in their political leadership.

He succeeded in lowering marginal tax rates and his signature legislative achievement, the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, provided the impetus for a global reduction in trade barriers that helped propel economies around the world down the path of prosperity.

At the time of his assassination on that dark November day in Dallas, he had gained confidence in his pragmatic approach to problem solving. How he would have dealt with Vietnam and whether he would have been able to pursue successfully an ambitious legislative agenda should he have been reelected remain the great unanswered questions.

Roger B. Porter, a professor at Harvard Business School and in the government department, as well as Master of Dunster House, teaches a course on the American presidency.

—Compiled by Nicholas P. Fandos

Read more in News

Equal Housing, Unequal HousesRecommended Articles

-

Murdoch, History of Science Professor, Dies at 83John E. Murdoch, a professor of the history of science and an expert in the field of medieval medicine, died of unknown causes Thursday. He was 83.

-

At 'Cliffe And Graduate Schools, First Female Grads Blazed Trails

At 'Cliffe And Graduate Schools, First Female Grads Blazed Trails -

In 1963, Early Roots Of Blossoming Civil Rights Movement

In 1963, Early Roots Of Blossoming Civil Rights Movement -

From the Archives: The Crimson's Coverage of the Kennedy Assassination

From the Archives: The Crimson's Coverage of the Kennedy Assassination -

For Dallas, a Day of ReflectionYes, our city bears responsibility for tolerating political extremism in the early 1960s, and we've coped with the deepest form of regret and ambivalence for five decades. But Dallas has become a city of great diversity and in many ways is emblematic of our country's future.

-

Best, Gabbard Honored with JFK New Frontier Awards

Best, Gabbard Honored with JFK New Frontier Awards