Twenty years after working on a Tim Murphy-led 3-8 Cincinnati team, Ravens coach John Harbaugh is preparing to coach in the Super Bowl. Two other former Murphy assistants are on Harbaugh's staff.

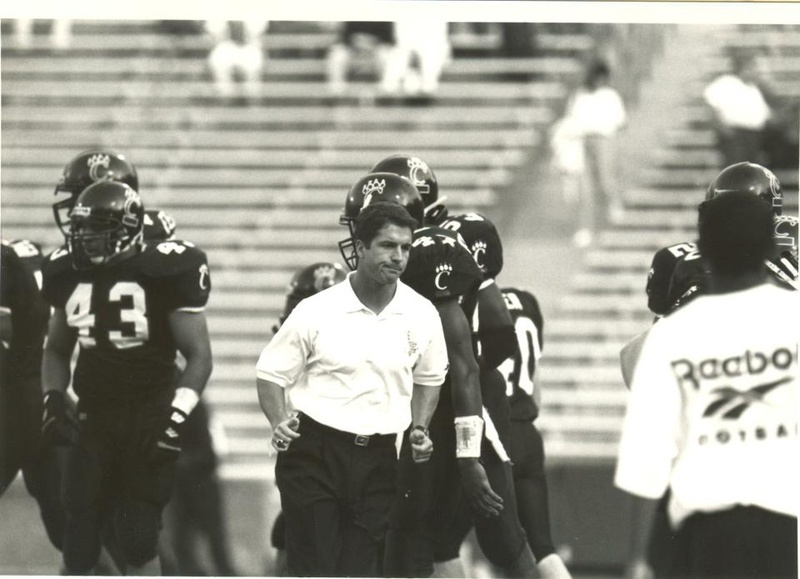

In 1992, his penultimate year as Cincinnati’s football coach, current Harvard coach Tim Murphy led his Bearcats to a 3-8 finish. More than 20 years later, a trio of assistant coaches from that team is preparing to man the sidelines at Super Bowl XLVII, but at the time, Cincy assistants John Harbaugh, Jerry Rosburg, and Craig Ver Steeg hardly looked like hot coaching commodities.

Harbaugh had just finished leading a special teams unit that finished 102nd out of 107 Division I teams in net punting. In his fifth year in the position, it seemed that Harbaugh’s football ascendancy had stalled for good after 10 years of coaching.

Rosburg, who helped Harbaugh with special teams and guided a linebacker unit that was part of the 62nd-best total defense, was in a similar position. Ver Steeg coached the quarterbacks and wide receivers to the 62nd-ranked passing attack and admits that his career prospects seemed bleak before coming to the Bearcats.

“I was looking for my first real opportunity back then,” Ver Steeg said. “I had been hanging on in college football. I was doing things like grad assistant, part-time guy, recruiting coordinator.… It’s hard, getting that first real shot to be a full-time coach.”

The story of how they went from a mediocre mid-major conference college program to the biggest stage in American sports is a parable about the determination and lucky breaks necessary to make it in the football coaching world.

Harbaugh grew up the son of a football coach and, after playing defensive back at Miami (Ohio), started a football coaching career of his own. While his background is fairly standard for the industry, his career path to the Ravens was anything but typical.

The coach got his start as a graduate assistant at Western Michigan and spent a year each at Pittsburgh and Morehead State. When Murphy left the University of Maine to take over in Cincinnati before the 1989 season, he asked Harbaugh to move once more.

Over three years, Harbaugh had three jobs, moving up in responsibility each time. But he stayed with the Bearcats after the 1989 season; then 1990 came and went without a better job offer. Pretty soon it was 1993 Cincinnati’s 3-8 season, and he remained in the same position. Coach Harbaugh had spent five seasons in the Queen City with little to show for it.

Harbaugh was frustrated and anxious that his rise might have reached its final destination. But looking back, the coach is thankful for his time under Murphy.

“There never has been a guy that I’ve been around who works harder, that is more detailed and covers every base,” Harbaugh said. “I think that was one of the biggest things that you learned as a young coach from ‘Murph’—that you were going to have to have all t’s crossed and the i’s dotted. As a young coach, that’s a great lesson to have. Plus, he was just an incredible friend, a guy who cares about players and cares about coaches. That’s important.”

Murphy’s wisdom might have been valuable, but ultimately it was his departure that sparked the renaissance of Harbaugh’s career. Due in part to the vacancies left when Murphy went to Harvard, Harbaugh was promoted to assistant head coach.

After two years as assistant head coach, Harbaugh got a job at Indiana University in the Big Ten, one of college football’s premier conferences. It took just one season there to catch the eye of the NFL’s Philadelphia Eagles, who hired Harbaugh to be their special teams coordinator.

The NFL coaching structure takes a completely different shape from its college counterpart. With fewer jobs and a plethora of quality candidates, keeping your job becomes the priority, with promotions coming as bonuses. For nine years, Harbaugh coached special teams in Philadelphia. In 2007, he moved within the organization to take charge of the secondary unit.

A year later, Harbaugh got an interview with the Ravens as they searched for a new head coach following the firing of Brian Billick. Baltimore decided to give him the head gig.

“I can’t tell you I thought he’d be an NFL head coach, but I’ll tell you one thing, he was a tremendous coach,” Murphy said. “He was a tremendously charismatic, impressive coach from the standpoint of his work ethic, his attention to detail, and ultimately what he got out of his players.”

After settling into his new position, Harbaugh began putting together his staff. When looking for someone to fill the role Harbaugh himself made his living for a number of years, the young head coach turned to Rosburg, his former Cincinnati colleague.

Up to that point, Rosburg had following a career path remarkably similar to Harbaugh’s. The former college linebacker left the Bearcats after the 1995 season and bounced around the college ranks before being hired by the Cleveland Browns to run their special teams, which he did for six seasons until Harbaugh brought him onto the Baltimore staff.

Ver Steeg’s resume shows a different growth path. While Harbaugh and Rosburg stayed in Cincinnati when Murphy took the Harvard job, Ver Steeg followed the man that gave him his first big shot.

“The fact of the matter was that there weren’t as many spots on his new staff as there were on his old staff,” Ver Steeg said. “I was thankful for the chance to continue with him.”

Ver Steeg did not just get job security when Murphy brought him to Harvard; he also got a promotion, as Murphy gave him more responsibility in the passing game.

“It was my first opportunity to put something together and start learning to be a coordinator,” Ver Steeg said. “That helped me for when I became a coordinator later on for sure.”

To this day, Ver Steeg thanks Murphy for what he did for his coaching career.

“I appreciated the chance that he gave more than anything,” Ver Steeg said. “I always appreciated the fact that here I was, a young guy that hadn’t really proven himself at all yet, getting close to 30, and he basically took a chance on me. I’ll never forget that…. I’ll always be in his debt.”

Ver Steeg spent two years in Cambridge before taking a limited role with the NFL’s Chicago Bears before the 1996 season.

From there, he dropped back to the college game, serving as quarterbacks coach at Illinois and offensive coordinator at Utah and Rutgers before reuniting with Harbaugh in Baltimore.

Now that Harbaugh has experience in the art of hiring a coaching staff, he respects the job Murphy did in the early 1990’s.

“The amazing thing about that whole deal was the staff that ‘Murph’ put together,” Harbaugh said. “He did great things in assembling and mentoring his staff…. ‘Murph’ was a young coach, and he didn’t know a lot of coaches, but he was a great interviewer of prospective coaches. He’d sit you down and you’d do a full-day interview. At the end of the day, he knew if you were his kind of guy or not.”

While the results of Murphy’s work might not have been clear during the 1993 season, they are evident with the benefit of hindsight. Murphy’s former assistants on the Ravens staff are just three of many members of Murphy’s coaching tree that now litter NFL staffs, including Tampa Bay Buccaneers defensive coordinator Bill Sheridan. And on Sunday, his one-time employees will take their shot at the sport’s biggest prize.

—Staff writer Jacob D. H. Feldman can be reached at jacobfeldman@college.harvard.edu.

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

CORRECTION: Feb. 3, 2013

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated the year in which current Harvard football coach Tim Murphy coached his penultimate season at the University of Cincinnati. In fact, it was 1992, not 1993.

Read more in Sports

Men's Basketball Looks To Continue Momentum Versus Rivals