If your father lived in Dunster, you’ll be greeted by a moose on Housing Day.

If your blocking group is on the small side, you’ll be Quadded.

Athletes are destined for Eliot.

Current Matthews residents are bound for Mather.

The children of celebrities and major donors can have their pick of the twelve Houses.

It’s the week of Housing Day at Harvard, and rumors are flying. As freshmen anxiously await the results of the lottery that will assign them to a House come Thursday morning, conspiracy theories abound.

Yet administrators assure students that all of them are untrue. Today, they say, after generations of evolution, Harvard’s ethic of randomization in almost all cases means just that—random.

A CLICK OF THE BUTTON

Around the end of February of their first year at Harvard, freshmen form blocking groups of up to eight classmates, then submit their names online into the housing lottery.

This year, freshmen were required to turn in their blocking groups by 8 a.m. on Feb. 29.

The Office of Student Life, which runs the lottery, spent the rest of the day tracking down the roughly 10 freshmen who did not register on time.

Once all these freshmen were added to a blocking group or registered as floaters, the OSL officially closed the lottery.

Next, the OSL pre-placed the blocking groups of students who registered disabilities ranging from mobility impairment to carpet allergies with the Accessible Education Office into a House that could accommodate their needs. This year, the OSL also randomly assigned a blocking group containing the child of House Masters into one of the nine Houses outside his parents’ neighborhood.

The OSL then determined the number of incoming sophomores that each House could accommodate based on expected attrition.

Finally, at 10:50 a.m. on March 2, Sophia R. Chaknis, the director of residential programs and operations, put on her Sorting Hat—actually donning a Harry Potter prop—then turned to the lottery software on her computer and clicked a button that randomly assigned about 1,600 freshmen to the buildings most of them will live in for the next three years.

“It’s literally just clicking a button,” said Associate Dean of Student Life Joshua G. McIntosh.

Specially designed by Harvard University Information Technology, the lottery tool meddles only with gender ratio.

In each freshman class, the ratio of male and female students placed in any House cannot stray from the current gender balance in that House by more than 15 percent.

Once the simple mathematical algorithm spit out the housing assignments, the OSL checked the results to “be sure the lottery logic is performing correctly,” McIntosh said. It has never failed them so far, he noted.

Finally, the Housing Day letters were generated. The fateful pages waited, ready to be picked up by upperclassmen to deliver on Housing Day morning.

McIntosh said the OSL receives about one or two phone calls after each Housing Day from students or parents who are concerned about housing assignments.

ENTROPY

The housing assignment process has become increasingly less grounded in student choice since University President Abbott Lawrence Lowell, Class of 1877, established Harvard’s residential House system in the 1930s.

Dean of Freshmen Thomas A. Dingman ’67 recalls that when he was an undergraduate, housing assignments were made through a competitive interview process in which House Masters selected interested freshmen.

Former Dean of the College Harry R. Lewis ’68 remembers of the House Masters’ selection logic, “If you had a string quartet that was part of the tradition of your House, you better make sure you have a cello.”

But in the 1970s, the policy changed. Students began ranking all the Houses in order of preference, taking the House Masters’ will out of the equation.

This shift came about as part of a “general movement toward student empowerment and student involvement,” Lewis said.

By the end of the decade, administrators modified the policy to limit students to ranking their top four Houses.

Under this revised system, students who received poor lottery numbers were sometimes unable to get into any of their top four choices and were instead randomly assigned to a House that still had vacancies—often in the Quad.

To avoid this fate, students sometimes sought to game the system by employing the strategy that Dingman remembers as the “Quad buster.”

According to Dingman, these students would apply to River Houses that they perceived as less popular to ensure that they would not be exiled to the Quad.

But for some, in particular African-American students, the Quad was the top choice.

Lewis recalls that African-American students told him that by choosing the Quad, they intended to make “a statement of being in but not of Harvard.”

In 1990, due to concerns about students self-segregating in certain Houses, administrators shifted to a non-ordered four-choice system.

But the composition of the Houses did not change.

The 1994 Report on the Structure of Harvard College, written by a committee which Lewis co-chaired, stated, “Our Committee is troubled that pronounced variations in the populations of the various Houses—with some Houses still having disproportionate numbers of varsity athletes, or members of certain ethnic or religious groups—result in those students being, as one person put it,‘educationally deprived’ because they have contact only with a somewhat homogeneous group of their peers.”

In 1996, The Crimson reported that only 4.8 percent of Eliot, Winthrop, and Kirkland residents were African-American, as opposed to 24.6 percent of residents of the Quad Houses.

After he took over as dean of the College in 1995, Lewis took over an effort begun his predecessor L. Fred Jewett ’57 to transition to a fully randomized housing lottery process.

The student-choice system “allowed the Masters and the House administrations and the College...to avoid problems that were problems of a minority of the Harvard population if that minority was underrepresented in their own House,” Lewis said.

This problem, Lewis recalls, was reflected in the sentiment expressed by some that homosexual students belonged in Adams.

Lewis recalls being disturbed by statements to the effect: “‘Oh, you’re gay and you’re unhappy. Well, why don’t you go to Adams House? They can probably take care of you.’”

In the spring of 1996, the first class of freshmen received letters assigning them to Houses which they had had no say at all in selecting.

Administrators tinkered with the system to add gender controls in 1997 and to reduce the maximum size of blocking groups from 16 to 8 in 2000.

Explaining the justification for the current eight-student rule, McIntosh mused, “Eight is enough for students to feel like they’re probably going to have maybe two or three suites, depending on the size of the rooming groups, of friends, and they’ll have other friends in the House, but at the same time, we won’t end up with floors or entryways of just a peer group. It seemed kind of arbitrary, and in some ways, it is, because what’s the difference between seven or nine?”

But other than those adjustments, administrators say that the existing fully randomized process has seen little change in the past decade and a half because it has effectively forced every student to confront diversity in his or her House.

As Lewis sees it, his experiment worked. “Randomization had the effect of making any problem everyone’s problem.”

—Staff writer Rebecca D. Robbins can be reached at rrobbins@college.harvard.edu.

—Staff writer Jane Seo can be reached at janeseo@college.harvard.edu.

Read more in News

Former Student Talks CartoonsRecommended Articles

-

Hoping for a New HomeThe competition for best House has always been a tumultuous one. Upperclassman housing at Harvard often means more than just ...

-

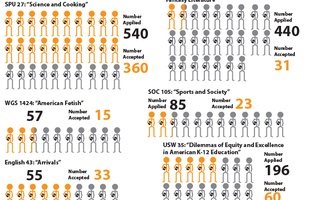

Lotteried Classes See Low Admission RatesIt is easier to gain early admission to Harvard College than get into a class with Harry Potter on the syllabus. While Harvard College admitted 18 percent of its early applicants in December, Professor Maria Tatar only admitted 10.5 percent of interested students to her class Folklore and Mythology 90i: “Fairy Tales and Fantasy Literature.”

-

Few Hit Jackpot In Course LotteriesAs the number of interested students in some already oversubscribed classes continues to grow and Pre-Term Planning data at times fails to accurately predict student interest, professors face the dilemma of how best to accommodate students while still maintaining the quality of their classes.

-

Senate Candidates Propose Differing Education PlatformsAs voters in the Commonwealth prepare to head to the polls on Tuesday to choose their parties’ nominees for the state’s open U.S. Senate seat, they will have to consider a number of education platforms ranging from consensus proposals to uniquely bold new ideas.

-

With Demand for Popular Courses High, Course Lotteries See Low Admissions Rates

With Demand for Popular Courses High, Course Lotteries See Low Admissions Rates -

The Love Song of An Awkward Prefrosh

The Love Song of An Awkward Prefrosh