Seated at Grafton Street Pub & Grill with a child-size glass of Guinness in hand, Professor Harvey Claflin Mansfield ’53, Harvard’s soft-spoken firebrand, has no intention of upturning the reputation he has earned during the nearly five decades he has spent teaching at his alma mater.

Even today, within a month of his eightieth birthday, Mansfield still relishes the battles he has fought over the years. Facing off against feminists, liberals, the new left, any enforcer of the politically correct, easy graders, and fresh young minds, Mansfield hasn’t pulled any punches. He has been a vigorous opponent of the Ivory Tower’s conventional wisdom. He’s against race and gender-based affirmative action. He categorically opposes gender studies departments. He puts the Constitution on a pedestal. He thinks women, in general, should be expected to earn less than men. He wrote a book entitled “Manliness,” a defense of traditional gender roles. In 2008, he hosted “The Conference the Radcliffe Institute Didn’t Want to Host.” He’s an unyielding critic of grade inflation, earning the moniker Harvey “C-minus” Mansfield. He even opposed Harvard’s course evaluation tool.

You could call him a polemic. But then you might be missing the point.

“Sometimes I think if Harvard was just as conservative as it is liberal now, I wouldn’t be a conservative,” Mansfield reflects, eating a BLT with avocado and picking at greens instead of French fries—even the great arbiter of manliness must bow to the requirements of old age.

Harvey Mansfield entertaining the thought that he could be himself without being a conservative—this idea seems pretty far from any regular conception of the Mansfieldian Platonic ideal. The words “I wouldn’t be a conservative” come from the same person who minutes later labels himself a “conservative Republican with the emphasis on Republican rather than conservative—because I like to win.”

The passing mention is not a half-hearted apology for decades spent as Harvard’s head heretic. He is not apologizing. In fact, Harvey Mansfield is first and foremost a philosopher—a man who has spent his career thinking about big ideas, a man who only half-jokingly lists John Rawls among his chief rivals. The idea of a Mansfield without conservative values is, like everything he touches, more complicated than it seems—or maybe more complicated than he likes to let on. Perhaps after spending a lifetime studying Nietzsche and Machiavelli, he understands the joy of the aphorism, of the provocative remark.

“I believe that Harvey is a provocateur, but I do not believe that Harvey is a superficial provocateur or an insincere one,” says Sharon R. Krause, a left-leaning political science professor at Brown University and a former Harvard government department Ph.D. student advised and mentored by Mansfield. “I believe that the position he defends, he believes he has good grounds for. But, he sees the limits of beliefs or convictions—even convictions that he believes are sound.”

Mansfield might be a man driven by the primacy of his conservative values, but maybe it is the confrontation itself that has kept him fighting.

***

Mansfield was born March 21, 1932, in New Haven, Conn. He arrived at Harvard—the son of Harvey C. Mansfield Sr., a government professor at Columbia—in 1949. Almost without intention, but with plenty of passion, Mansfield immersed himself in the study of government—describing himself as a “grind.” As Mansfield, who went to a public high school, says he was a member of Harvard’s first class to have equal numbers of men from prep schools and public schools, he revels in his own brand of diversity.

After he graduated, he spent one year in England on a Fulbright scholarship and then two years as an enlisted man in the Army.

He received his Ph.D. from Harvard in government in 1961, taught at Berkeley for a couple of years, and then returned to Harvard as a lecturer. In 1969, he was appointed a full professor; he chaired the government department from 1973 to 1976. Today, he is the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Government.

During his time as an undergraduate, Mansfield was not yet a neo-conservative; he was a liberal. In a straw poll in the 1950s, he even voted for Adlai Stevenson.

Then, in the late 1950s, Mansfield recalls—employing a phrase coined by the neo-conservative thinker Irving Kristol—getting “mugged by reality.” His transformation came in two parts. First, Mansfield discovered Leo Strauss, a Jewish-German political philosopher who has had a sustained impact on Mansfield’s scholarship and worldview. Strauss’ views on history and the classics naturally translated into a conservative school of thought, Mansfield says. Second, the protests that erupted in America and on Harvard’s campus during the Vietnam War shaped his political perspective forever.

Paul A. Cantor ’66, an English professor at the University of Virginia who participated in a reading group led by Mansfield during his time at Harvard, says, “When you had these various forms of student protest and politics suddenly intruding on academics, you suddenly had to take political positions because the students were forcing you to. Those events I wouldn’t say politicized him as a teacher, but they made it necessary to make certain political positions.” Cantor recalls, “Students would barge into your class and try to stop you from teaching.”

Mansfield kept teaching.

“Many students refused to go to class after the American invasion of Cambodia, and Harvey Mansfield taught when many other faculty cancelled their classes,” says Nathan Tarcov, who received his government Ph.D. at Harvard under Mansfield’s mentorship.

***

Mansfield has kept teaching—and researching, and writing—for the past five decades, but he says he feels he has been passed over by the academic elite. He mentions, for one, that he’s never been honored by the American Political Science Association. “It doesn’t bother me a whole lot because it goes with the territory,” he says, referring to his conservative convictions and controversial stances.

“I think he has gotten less credit than he deserves...some of that is undoubtedly because of politics, some of it is because his work is difficult,” says William Kristol ’73, a preeminent Republican thinker and the founder of The Weekly Standard. “He hasn’t pulled his punches. I don’t just mean that in a political sense; I mean that in an intellectual sense.”

It’s not that he’s gone entirely unacknowledged, but that the plaudits have come almost exclusively from his fellow conservatives. He’s been to the White House five times: once under Gerald Ford, twice under George H.W. Bush, and twice under George W. Bush. In 2004, he won the National Humanities Medal, and in 2007, he served as the Jefferson Lecturer in the Humanities—“thanks to George W. Bush.”

Amidst academia’s quest for diversity, Mansfield believes that the most important kind—intellectual diversity—has been forgotten. He says he watched the primacy of Western civilization evaporate. The classics have fallen off the canon. Great books are no longer considered indispensable in liberal arts institutions. He sees a government department that has little interest in studying the military or the minutiae of the Constitution. And to make matters worse, faculty members are more and more willing to coddle their students.

Mansfield sees it as his mission to try to attract faculty members to Harvard who will question this “political correctness.” “One of the worst things about democracy is conformism,” he says.

“I get angry,” Mansfield says, breaking his calm and professorial speaking voice. He invokes his favorite foe, “feminists”—which he often applies as a catch-all term for his ideological opponents—and splutters: “They’re so intolerant.”

But conservative academics are routinely overlooked by the University—not on political grounds but because of their old school academic interests, he says. “If you’re from another point of view, you probably study different things.”

The problem transcends Harvard. Mansfield is routinely frustrated when his graduate students don’t get appointments at other universities, and he bristles at the suggestion that this is because of anything other than a bias against their approach. “It’s not just a feeling,” he declares. “It’s an observation.”

Mansfield wants Harvard to practice affirmative action for conservatives. “I think a certain kind of affirmative action—searching out, not quotas,” he says. “Looking out for people who are different from what we have.”

Now with a barer plate in front of him, Mansfield has hit his stride. He cites Commencement speakers as another example of Harvard’s prevailing liberal bias. Then he adds that Harvard Yard has only been shut down for two term-time speeches: Jesse Jackson and Al Gore ’69.

“Harvard never gave an honorary degree to Margaret Thatcher, the mightiest woman of our time,” he rails.

***

He may consider himself first and foremost a political philosopher, but he’s perhaps best known as an antagonist in an area in which he can claim no extensive pedigree: gender. He wrote the book “Manliness” in 2006 and made an appearance on “The Colbert Report” to promote it.

The book argues that men and women have inherent differences due to nature and social construction, and that they should remain different. He says it should be expected that women will earn less than men. He says that women will always be less focused on their careers than men: “I do think they will always be less single-minded,” he says. “They want a family in a way a man does not. I think most women think about being mothers, but a man doesn’t think about being a father until he is one.”

His book was slammed in a New York Times book review. It also received strident criticism in a piece written by Martha C. Nussbaum, a political philosopher at the University of Chicago, appearing in The New Republic entitled “Man Overboard.”

“To begin with, it is slipshod about facts—even the facts that lie at the heart of his argument. He repeatedly tells us that ‘all previous societies have been ruled by males,’ producing Margaret Thatcher as a sole recent exception,” writes Nussbaum in the article, proceeding to refute Mansfield’s claim by citing more than two dozen female leaders missing from his tabulation, including politicians in New Zealand, Turkey, India, France, and Canada.

But in typical Mansfield style, faced with a lengthy recitation of Nussbaum’s critique, he says, “No, I think it’s true: All previous societies have been ruled by men—and Elizabeth. I’ll add Queen Elizabeth to that,” he says. “That’s my concession.”

After some prodding that Nussbaum might be empirically correct, he says: “Those are recent, and they’re not significant.”

“I’ll stick with Margaret Thatcher,” he says.

In the piece’s conclusion, Nussbaum—an esteemed political philosopher who has won a number of mainstream academic awards and honors—writes that “Manliness” has a “lack of definitional clarity,” an “ideological enthusiasm,” and “a tendency to romanticize characters” in a way that makes the book “uncourageous, just when we badly need to think well about how to cultivate true courage.”

Again, asked to respond, he pauses and takes his time to collect his thoughts. “The last thing Martha Nussbaum wants is true courage,” he says, “because true courage would be exercised against her very politically correct position.”

“She’s a classical scholar and philosopher, and she paid no attention to my discussion of Plato and Aristotle in the last two chapters of the book,” he says.

Her piece does, in fact, address Plato and Aristotle. Whether it pays sufficient attention to his discussion is a question that seems unanswerable when faced with unyielding disagreement between two highly credentialed minds.

For her part, Nussbaum writes in the article that Mansfield might not be the patient philosopher but instead be a familiar character from Plato’s dialogues: the sophist. “Far from seeking truth, the sophist seeks to put on a good show. Far from wanting premises that are correct, the sophist seeks premises that his chosen audience will find believable.”

In “Manliness,” Mansfield did not attempt to grapple with homosexuality. He says that he testified on behalf of the “anti-gay” side in a Colorado court case, but that it’s not really his issue. “I don’t care that deeply,” he says about gay marriage. “Some things are bigger problems than others.”

Then, atypically, he acknowledges that social change has brought with it actual progress. He quietly mentions a gay classmate of his who committed suicide. “It’s good that we don’t treat gays in such a way that we used to,” he says.

***

Mansfield does not look like somebody obsessed with manliness. You might have to lean in to hear exactly what he’s saying. He never played varsity sports as an undergraduate. “I’m pretty small,” he says. He is a fan of football (he tries to go to every home game), hockey, and basketball (about Jeremy Lin ’10, he says, “I’m ruing the day that I never saw him play”).

He also played squash socially; Kristol recalls their time spent playing against each other: “He probably won more often than not.” These days, Mansfield makes sure to walk down the stairs from his fourth floor office in the Center for Government and International Studies to get exercise. He looks spry for almost 80, but he’ll need a hip replacement at the end of the spring semester.

Mansfield is going on leave during the 2012-2013 school year. He has no plans to retire, but he says he’s well aware that “senility can sneak up on you.”

Mansfield drives a gray Porsche Boxster, and an old Lexus when he’s going to get the groceries. He has been married three times. His first wife Margaret Dittson Mansfield, the mother of his three children, divorced him and later died in a 1989 automobile accident along with one of his children. He married Delba S. Winthrop, a professor at the Harvard Extension School, who died of cancer in 2006. He has since remarried again, this time to Anna Schmidt, whom he met in Munich during a research professorship there. “She’s the one who opened the taxi door for me,” he says, describing how the pair met.

At Crema Café, Schmidt—a 37-year-old with wavy hair, a fur coat, glasses, and too much energy for 9 a.m.—says her husband is not exactly what you would expect from the author of “Manliness.” When it comes to moving furniture around the house as they renovate the living room, she’s the one doing any heavy lifting. And in debates—which she typically instigates, rather than her more subdued husband—she says she can hold her own. She’s perhaps most critical of her husband not when he talks about feminism but when he spends too much time and energy watching sports.

He is a man who is skeptical of anyone who claims to know truth. “One thing that makes me angry is open and aggressive atheism,” he says. “Religion can be aggressive if it makes you think God is always on your side.”

Today, near 80, he calls himself “just only officially” a Christian. “I respect them,” he says. But: “In practice I don’t believe. In practice I’m one of those two,” he says, referring to atheism and agnosticism. “Philosophers as such are more likely to be skeptics.”

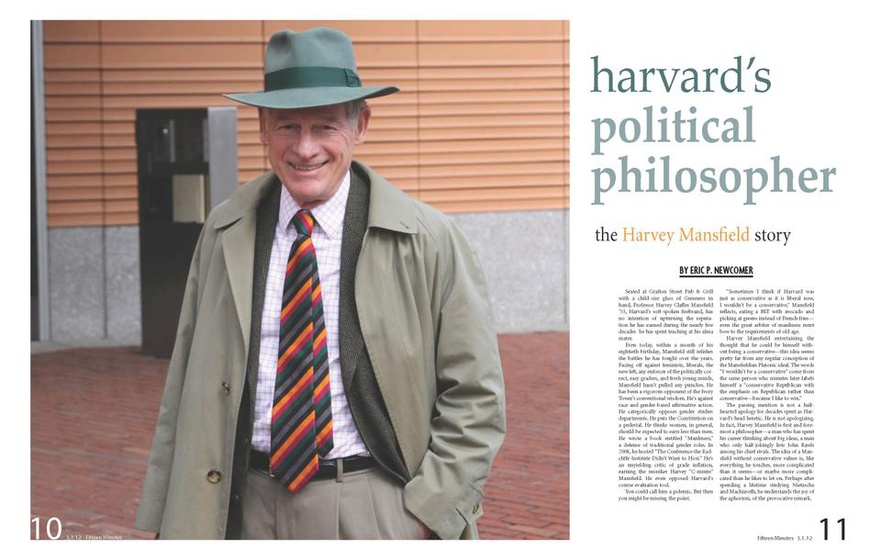

He is a dapper dresser, wearing a coat jacket, a brimmed hat, and a colorful striped tie—the kind that only old men seem to get away with. “He’s one of the best dressed people I know and he cares about it,” says Jerry Weinberger, a political science professor at Michigan State University and a former government department graduate student mentored by Mansfield. “He’s a gentleman. That’s what he is, in all the best meanings of that term.”

Mansfield is old, but he is not a political relic. He says that he is not against social safety net, for instance; he just thinks it is too big and encompasses too much of the middle class. “I’m not a fanatic,” he asserts.

He has picked a candidate for the 2012 Republican nomination. “I would support Romney as the best of what is being offered by the Republicans,” he says.

***

While Mansfield’s public persona is largely tied up in his political and social views, for many of his former students, those attitudes take a back seat to his qualities as a teacher.

“I remember to this day his first lecture: It was so witty,” says Kristol, who went on to get his government Ph.D. under Mansfield. He describes Mansfield’s lectures as “a very unusual combination of incredibly dense on the one hand and incredibly entertaining.” The lectures, Kristol says, were broadly apolitical, but Mansfield took to “taunting the students to break out of their complacence”—an attribute lauded by many of Mansfield’s former students.

“His seminars and lectures were always meticulously crafted; at least for me, they were always designed for and succeeded in prodding students to think through problems themselves. He expected you to learn. He expected you to stand on your own two intellectual feet,” Weinberger says.

Mansfield says that Harvard hasn’t given him a single award—except his 1993 Levenson Memorial Teaching Prize, from which he derives a healthy amount of pride. “Maybe I’m more of a teacher than most people are,” he says.

He tends to score above the average for the social sciences on the Q course evaluation tool, the same tool he once outspokenly opposed. The comments on his course Government 1061: “The History of Modern Political Philosophy” warn of a dense reading list—Machiavelli, Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau—while at the same time offering whole-hearted endorsements.

One comment reads: “Be ready for a lot of reading, but if you are into deeper questions, you will really enjoy this course. It doesn’t focus on details, but talks about the bigger questions of life and politics, and focuses on philosophizing instead of memorizing.”

Mansfield teaches philosophical texts that are sometimes centuries old, and he tries to push students to consider the possibility that the claims in the texts are true. Unlike some philosophers who see a general march forward in intellectual thought, Mansfield pushes his students to consider the possibility that these ancient texts got it right—and that maybe it was in the time that followed that people went astray.

“He made these books speak for themselves. That’s a great gift. It’s in a way uncomfortable, because when these books speak for themselves, they shake you up,” Weinberger says. “Every book that I studied with him, we took it seriously like it had been written yesterday.”

His fellow professor in the government department Michael E. Rosen says the reason for Mansfield’s effectiveness as a teacher is obvious. “He’s someone who’s intensely engaged with individuals and text. You can tell this is someone who’s read with extraordinary care and loves what he’s reading,” he says.

Yet one would be remiss to describe Mansfield as a teacher without acknowledging his abilities as a performer. Mark Lilla, a professor at Columbia and former Harvard government graduate student mentored by Mansfield, fondly recalls his time spent in Mansfield’s class. “Political philosophy suddenly seemed urgent,” he wrote in an email. “And he was unbelievably droll. He liked making slightly racy or un-PC asides now and again, just for the fun of hearing the Harvard hiss return from the students (which meant they were awake).”

***

To truly understand Harvey C. Mansfield—a man whose solution to grade inflation at Harvard is to give students one grade, the one they deserve, and then another, the ironic grade, which goes to the Registrar—you have to realize that he tries to think outside history. Or, at least, he likes to pay a bit more deference to the old ways than the rest of us.

His is an uncommon voice at Harvard, broadly opposing the notion that progress is for the better. “Society always takes things for granted,” he says. “If one looks at modernity from the outside, one is not so impressed by the latest thing or the newest thing.”

Perhaps Mansfield stumbled into his role as provocateur by dint of his conservative worldview, but this script has become one that he acts out with both intellectual honesty and an understated self-awareness. No one will ever know for sure what Mansfield would be like at a conservative Harvard. In this world, however, he has become one of the most visible elements of intellectual life on campus. Some might say that his clamorous dissent has done more harm than good. On the other hand, even if his views lose out in the march of history, there’s something to be said for Mansfield dragging his heels and throwing intellectual barbs along the way. Maybe it means that progress comes with more honesty.

Mansfield recalls a time when the University of Chicago offered him a position on their faculty. Harvard’s government department chair at the time asked Mansfield not to leave, calling him the department’s balance. “I don’t count as diversity,” he scoffs. “I count as balance.”

But despite his frustrations, he has a deep affection for Harvard and his many friends among the faculty. “I love Harvard,” he says. “But I have my quarrels.”