When Hobart G. Armstrong Jr. ’63 donned his helmet and his #40 Crimson jersey to step onto Soldiers Field in 1961, he was the only black man on the football team. When Spencer C.D. Jourdain ’61 sang in harmony with his fellow Harvard Glee Club members, what made him stand out amongst his peers wasn’t the color of his crimson suit jacket, but the color of his skin.

Although there were roughly six black undergraduates in the Class of 1961, black students didn’t always experience the discrimination that some might expect would accompany their minority status.

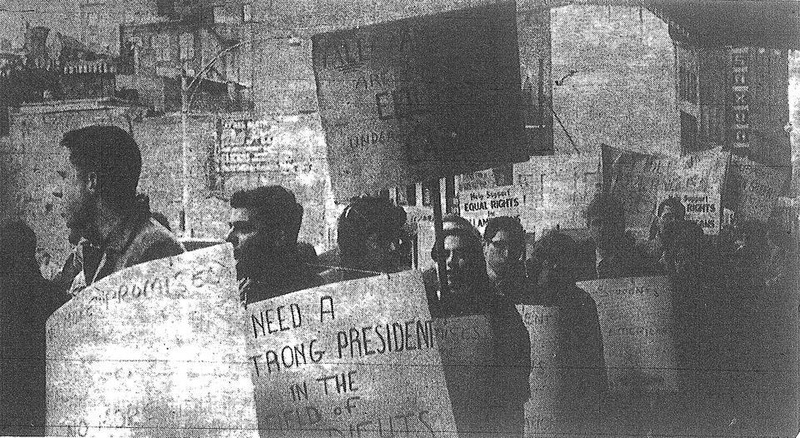

With lingering ’50s-era McCarthyism and Cold War fears continuing to suppress outspoken activism, the year 1961 signaled a relative lull in civil rights protest at Harvard, as black students became involved in extracurricular activities and felt integrated in the broader college community. Although many say they did not experience significant discrimination at Harvard, growing racial tension off-campus would slowly raise awareness of racial issues among students, eventually igniting vibrant student activism in the late ’60s.

MCCARTHYISM LINGERS ON

On Harvard’s campus, the ’50s and early ’60s served as a period of relative silence on civil rights before activism boomed in the later ’60s.

“Civil rights was just a topic among topics,” Jourdain says. “It certainly wasn’t the dominant issue at the time.”

But just a few decades earlier, Jourdain’s father Edwin Bush Jourdain, Jr. ’21 had spearheaded the movement to desegregate the dorms during his own time at Harvard.

“It was very different than the ’20s, when among the African-American students, [race] was a vociferous issue,” Spencer Jourdain says. “But in the ’50s and early ’60s among students and even African-American students, it was not nearly as intense.”

Wandering the aisles of the activities fair during his freshman year in 1959, John N. Woodford ’63 was warned by his friends to think carefully about the student groups that he signed up for.

Rather than being concerned about him over-committing himself while adjusting to his new life at Harvard, Woodford says that his friends still held lingering concerns about the era of McCarthyism in which people who engaged in activism and anti-government activity were seen as suspect.

Some people still believed that associations with socialism or communism, even if only in the form of signing up for a student activist group’s list, could ruin their reputation and even their careers later on in life, Woodford says.

But the early ’60s marked a transition period between that fear of action—instilled in the American population by organizations such as the House Un-American Activities Committee—and the later activist generations that would risk both their position at the University and their lives in the fight for racial equality.

The mixture of these two mentalities meant that a slow but constant evolution into a new era marked the period.

“It was a mix of the dying ’50s and the emerging ’60s, so there were a lot of different currents at the time,” Harvard Kennedy School Lecturer Marshall L. Ganz ’64-’92 says.

BEYOND RACIAL BOUNDARIES

Read more in News

Electing Youth and Change: Kennedy on Harvard’s Campus