Upon returning to campus, the observant among us have likely noticed the Busch-Reisinger Museum’s sudden disappearance from the Prescott Street skyline. Some may just have grumbled as they were funneled into the pedestrian walkway on their way down Quincy Street. Others see the renovation of Harvard Art Museums—encompassing the Busch-Reisinger Museum, the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, and the Fogg Art Museum—as a refreshing change of scenery. “Temporarily removing much of the uppermost part of the Fogg admits far more light into the [Visual and Environmental Studies (VES)] studios,” says VES Professor John R. Stilgoe.

Though spoken in jest, Stilgoe’s response typifies much of the Harvard community’s attitude towards its art museums. They are appreciated as familiar features of the landscape, and for the light they shed on our chosen fields of study, but otherwise largely overlooked. “I think students who have taken History of Art and Architecture (HAA) classes or who have spent time at the museum absolutely appreciate it,” says Alexandra Perloff-Giles ’11, President of the Harvard Art Museum Undergraduate Connection (HAMUC) and a former Crimson arts columnist. “But I think there are many students who don’t know what an amazing resource we have.”

Far more than a physical reorganization, the renovation now in progress aims to combat the lack of recognition identified by Perloff-Giles, along with museum administrators past and present. While many Harvard classes incorporate a token art-viewing ‘field trip’ into their schedules, the museum’s potential as an interdisciplinary resource remains largely untapped. The renovation currently underway looks to reposition Harvard’s art collections within the landscape of the university and within the greater public community—to allow its diverse holdings to illuminate other areas of study, and not just the adjacent buildings.

A SECOND LOOK

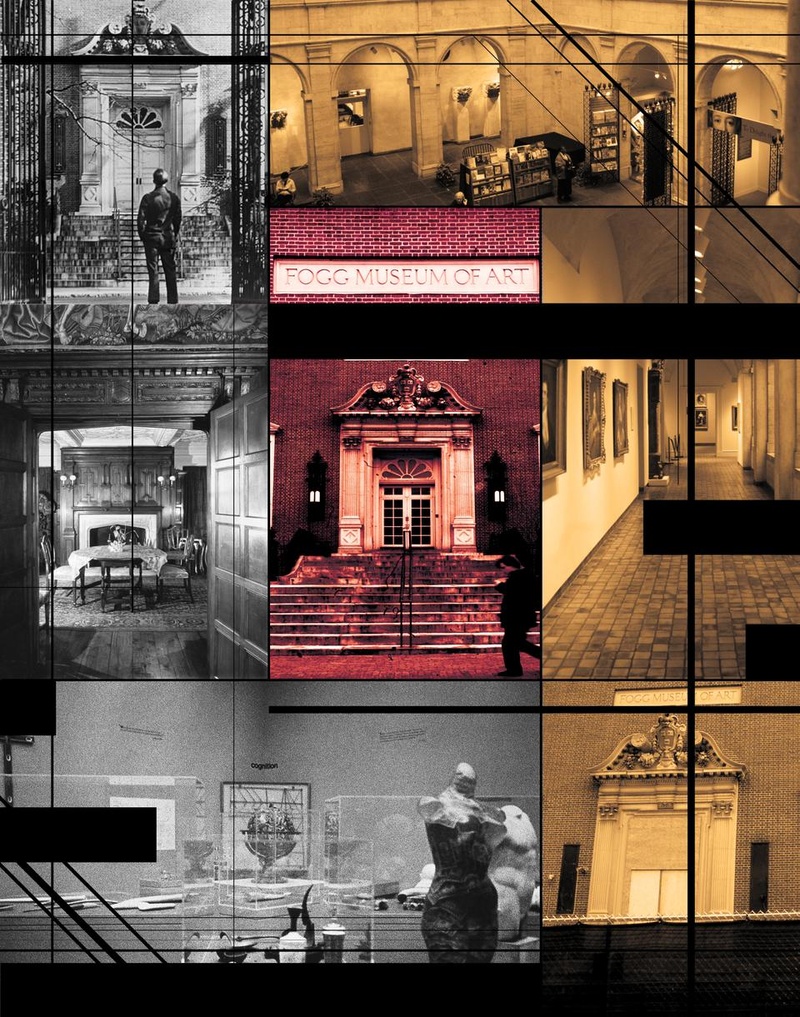

Since construction began in 2008, the famed Fogg Art Museum—historically seen as the heart of the HAM complex—has been closed to visitors. Though the Sackler Museum showcases a selection of important works throughout the renovation in an ongoing exhibition entitled “Review,” only this year’s seniors have enjoyed full access to the active Fogg and Busch-Reisinger buildings during their time at Harvard. This inaccessibility may account for the relatively low profile among students of Harvard’s world renowned art collection, the sixth largest in the United States.

Founded in 1895, the Fogg was the first of the Harvard museums. The collection moved from its original location—now the site of Canaday Hall—to the Quincy Street site in 1927. Over the following eighty years, seven additions were built onto and around the Quincy site, including the Fine Arts Library, Werner Otto Hall—formerly home to the Busch-Reisinger Collection—and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum. The scattering of new additions made for an increasingly fragmented viewing experience. The collections were rigidly divided along cultural lines—the Sackler holding Asian, the Busch-Reisinger Germanic, and the Fogg predominantly Western art—while the rambling layout impeded easy circulation and study.

Excluding the Sackler, all such later additions have now been demolished with an eye to consolidating their holdings in a sizeable new wing on the back of the Fogg. According to Thomas W. Lentz, Director of HAM, one of the project’s primary objectives is to fuse the disparate collections together within one functional, streamlined space. “Our goal is to consolidate them on one site, under one roof, as one destination,” Lentz says. “What we like about this idea is that it allows us to have a much greater dialogue between those three collections.”

PURE AND SIMPLE

In order to draw the attention of passers-by, HAM has enlisted internationally-renowned architect Renzo Piano and local design group Payette associates to craft a museum fit for the twenty-first century. Still, according to HAM’s Director of Facilities and Capital Planning Peter J. Atkinson, “there aren’t a lot of bells and whistles. It’ll be simple in many ways.” The choice of simplicity is both an aesthetic and strategic decision. “[Renzo’s] architecture doesn’t dominate the art,” Atkinson says. “[He] quietly has built buildings that are spectacular.”

Both Atkinson and Lentz stressed that though the museum’s design will be cutting-edge, functionality and navigability are its main priorities. Atkinson anticipates a finished product that maximizes natural light and takes the Fogg’s surroundings into consideration; “Renzo Piano is giving us a rationalized, transparent and flexible building, ” Lentz says. Architectural flourishes and attention-grabbers may be unnecessary, given the museum’s advantageous location within the University. “We actually fit right in middle of a visual arts cortex, right in between the Graduate School of Design and the Carpenter Center, right on the edge of Harvard yard,” Lentz says. “We [are] very well positioned as a kind of hub and connector.”

The building’s stylish yet functional aesthetic will be achieved through environmentally sustainable construction techniques. The project is angling for a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Gold certification from the United States Green Building Council (USGBC), the second highest rating on their scale. Over the course of two years spent emptying the Fogg’s galleries and offices, HAM reached out to two dozen local organizations that claimed and reused 30 tons of material—from office furniture to exhibit cases, from easels to teak flooring.

CLIMATE CHANGE

HAM decided not to aim for USGBC’s highest rating in order to maintain an art-friendly climate around the clock. Atkinson concedes that this pursuit inevitably requires high energy expenditures, but it serves an important purpose. “We always say, ‘The art never goes home’,” he says. “While most people live in a building during the day or they live there at night, the art is in the building 24/7. And that’s why we’re using a lot of energy: we’re building for the art and we want it to feel comfy all day long.”

High standards in climate control are vital to HAM’s position in the artistic community. Opened in 1927, the original Fogg lacked even the most basic technologies necessary to safely house and preserve works of art. As researchers discovered the detrimental effects of certain temperatures and levels of humidity on works of art, unequipped museums like the Fogg lost the ability to borrow works from other institutions. This meant that temporary exhibitions were far less frequent—an unfortunate development in light of the fact that the museum had previously secured the work of William Blake in 1920, Fra Angelico in 1930, and Paul Gaugin in 1936. For two weeks in 1941, Pablo Picasso’s famed “Guernica” hung in the Fogg’s Warburg Hall; as a point of pride, the hook on which it hung was symbolically in the wall until the museum was dismantled. With a new facility that meets modern standards of art conservation, HAM may again borrow pieces of similar magnitude for display and study.

WEATHERING THE STORM

Read more in Arts

Bicycles Mobilized as Art in Annual International Festival