Every Tuesday in the fall of 1960, a group of six students gathered in the living room of Winthrop resident tutor Robert P. Wolff ’54. There, along with Sociology Professor Barrington Moore, they would discuss the likes of Marx, Freud, de Tocqueville, Nietzsche, and Durkheim.

“It was just two professors in a living room going at you for two hours—it was very heavy stuff,” said Wolff, then a philosophy and general education instructor. “When Moore was done with them he’d pass them off to me. The kids were just plastered up against the wall. The first week’s reading was the ‘Wealth of Nations.’ We were insane.”

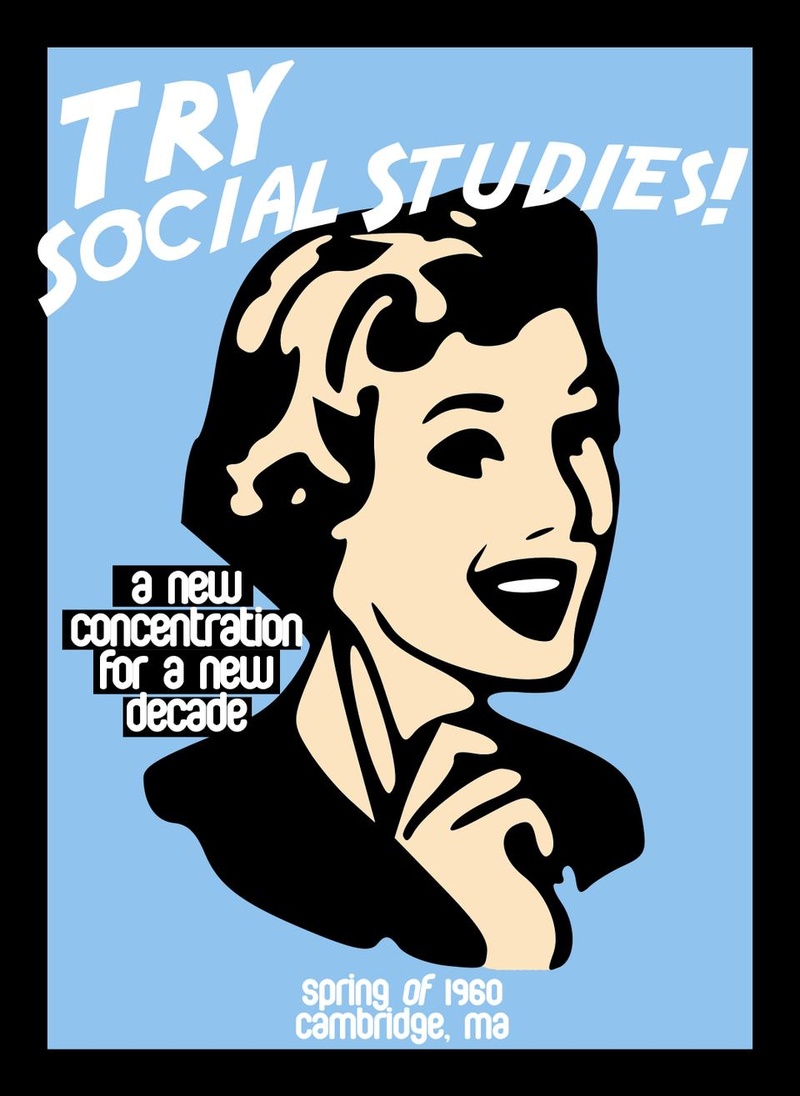

The meetings in Wolff’s living room marked the beginning of what is now one of the most popular concentrations on campus, Social Studies. In 1960, 15 students in three tutorials embodied the realization of a plan for an interdisciplinary and comprehensive concentration that had been years in the making. While the program has flourished over the years, some complications and doubts surrounded its formation.

AN INDIVIDUALIZED EDUCATION

Initially, many of the departments that the Committee on Degrees in Social Studies sought to integrate—such as Government, History, Economics, Anthropology, Philosophy, and the now discontinued Social Relations department—had qualms about the addition of a new concentration that could steal some of their best professors and brightest students.

“It’s a traditional and universal fact of the higher education system in America,” said Wolff, who became the concentration’s first head tutor. “The creation of departments means that existing departments might lose students, and they use those statistics about majors to justify their funds.”

Stanley H. Hoffmann, government professor and one of the founders of the committee, admitted that Social Studies did indeed take many of the brightest students on campus from other departments, but he insisted it was necessary.

“People want to get out of little boxes,” Hoffmann said. “You cannot separate politics from the study of history or economics. Equations and models are one thing, but human beings are another.”

However, professors and administrators continued to push back, fearing that an interdisciplinary concentration would simply be far too broad to keep up with the academic standards Harvard demanded.

“The departmentalization of academia was a 19th century idea,” Wolff said. “The notion that sociology was separate from history or history was separate from politics or economics would have struck the people of the 19th century as nuts. Marx wouldn’t have thought that. Durkheim wouldn’t have thought that.”

Students saw the breadth of the concentration as a distinct advantage. “It was great, broad, and it meant that I didn’t have to narrow myself,” Charles A. Stevenson ’63 said. Stevenson, a member of Wolff’s first tutorial, returned to co-teach Social Studies’ international relations junior tutorial from 1968 to 1970. “It kept more options open longer. My mind got stretched by my sophomore tutorial more than any other experience at Harvard.”

Current Social Studies Director of Studies Anya E. Bernstein said that the concentration has always been personalized. “Students follow their individual academic paths, and they get a lot of support in that process,” Bernstein said.

INITIAL CHALLENGES

While Social Studies was able to borrow senior faculty from other departments, the committee as a whole has struggled to build a solid and lasting base of professors. In its first 40 years, not a single junior faculty member received tenure from the committee.

“It is a strength and weakness that the department has attracted so many junior faculty members,” Hoffmann said. “In my opinion there are not enough senior members teaching.”

Read more in News

Sanskrit Dept. To Change Name, in Pursuit of Interdisciplinary WorkRecommended Articles

-

Epitaph For the SunPlease sell $10,000 worth of stock. We have decided to lead a mad and extravagant life. H ARRY CROSBY, scion

-

Professors Score U.S. Policy In Seeking Middle East PactStanley H. Hoffmann, professor of Government, and Nadav Safran, professor of Government, both warned last night that if a settlement

-

A Moving PseudomemoirIf the words “curriculum vitae” set you shuddering with career anxiety, Yoel Hoffmann’s new work goes a long way to

-

Protestors Fight Against Marty Peretz

Protestors Fight Against Marty Peretz -

Harvard Law School Panel Urges Repeal of 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell'Four panelists at yesterday’s Harvard Law School Dean’s Forum agreed that “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” should be repealed, denouncing the policy as “inhumane.”

-

New Book Uncovers How French Art Scene Continued Under Nazi OccupationFormer New York Times correspondent, Alan Riding held a lecture yesterday to discuss his new book, “And the Show Went On: Cultural Life in Nazi-Occupied Paris,” which gives a glimpse into the response of French intellectuals under Nazi occupation.