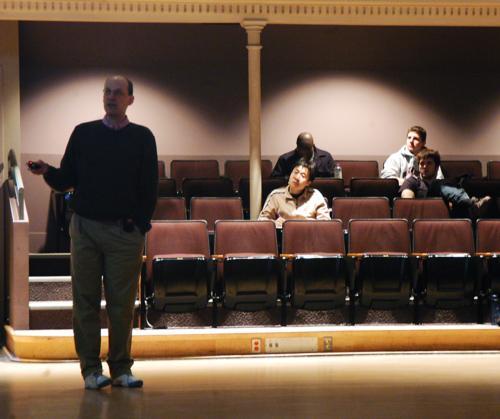

Professor Christopher L. Foote teaches his course, Economics 1010b, in Lowell Lecture Hall last Friday. With little training in transition or development economics, the professor helped nationalize Iraq’s currency and sell free market ideas to Iraqi cit

The man teaching Ec 1010b this spring knows how to put macroeconomic principles into action.

In May 2003, economist Christopher L. Foote flew to Baghdad to help rebuild Iraq’s economy. He was part of a team of American economists charged with revitalizing Iraq after decades of devastating international sanctions and repressive state control.

First, though, he had to find his way to his office.

The team of economists was headquartered in Saddam Hussein’s Republican Palace, and Foote often found himself wandering bewildered through its garish, gilded rooms. The light fixtures were painted gold, he said; the crystal chandeliers, at a closer look, were plastic.

Foote came to rely on the compass in his watch to find his way to his office. When in doubt, he would follow its arrow south.

“There’s a great sort of allegory in there somewhere,” Foote said.

The American economists knew almost nothing about Iraq. They were charged with reconstructing its entire economy. And Foote thought that with the tools they had—the free market principles freshmen learn in introductory classes—they could do it.

‘A CAPITALIST’S DREAM’

In September 2003, The Economist ran a story on America’s rebuilding of the Iraqi economy titled, “Let’s All Go To The Yard Sale.” The American economic reform program represented an unprecedented application of free-market principles, the article said. “If it all works out,” a caption read, “Iraq will be a capitalist’s dream.”

Despite the inflated rhetoric, Foote said, the article captured something real about the reconstruction efforts. The team of about 15 American economists under the direction of former Michigan State University president M. Peter McPherson, had been given what Foote and his colleagues would later describe in a published paper as “sweeping powers” to shape the structure of Iraq’s economy.

“When we got there, it was pretty much a blank page,” Foote said.

In terms of trade or monetary policy, “pretty much anything was on the table.”

Foote said that economists who want to implement free market policies usually have to struggle against unions, business groups, and other entrenched interests.

In Iraq, Foote said, “We didn’t face those kinds of constraints.”

“The country,” he said, “was flat on its back.”

The list of policies Foote and his colleagues laid out to revive Iraq’s markets sounds like a declaration of economists’ central dogma.

The American team created a unified national currency, worked to strengthen the bank system, suspended all tariffs, and, most controversially, opened Iraq completely to foreign investment.

Together, these policies represented “the kind of wish-list that foreign investors and donor agencies dream of for developing markets,” The Economist wrote.

The economists—who are “sometimes justifiably criticized for thinking that they have all they answers,” Foote said—had been given an incredible amount of latitude in crafting policy.

“It was definitely very exciting to say, okay, we have a developing country, what should the tariff be? Should it be zero? No, because we need some tax revenue,” Foote said.

Officially, the American economists’ policy recommendations needed approval from only one man, L. Paul Bremer III, the head of the Coalition Provisional Authority.

Later in the summer, they also needed to get de facto approval from the Governing Council, a handpicked group of Iraqi leaders, Foote said.

Still, the ability to exercise so much influence was “exhilarating,” Foote said.

It could also be terrifying.

“If things went bad, they could go really bad.”

And while the American economists had a maximum of influence to shape Iraq’s new economic policy, they also had a minimum of information.

‘VIRTUALLY BLIND’

In the months after the invasion, the Baghdad markets were bustling. Imports had flowed into the country, and venders were hawking shampoo and string and a dazzling array of pirated DVDs. “There was basically anything you could think of,” Foote said.

But he wasn’t able to buy any of it. “We were told it was not a good idea to go outside,” Foote said. He had to observe the market from the window of an armored vehicle.

Foote had been working for the Council of Economic Advisers in Washington, D.C. when he volunteered to come to Iraq in the early spring of 2003.

Foote, who had started teaching economics at Harvard straight out of graduate school, knew very little about Iraq, and he had no special expertise in development economics.

But he was not married and did not have children, two factors that made other experts reluctant to go to Iraq, Foote said.

“To be honest with you, they were happy that I volunteered,” he said.

“There weren’t that many people volunteering.”

Foote said he figured that his broad knowledge of macroeconomics and an ability to quickly find answers to what he did not know would be enough to make him useful in Iraq.

“You’d have to be an idiot to go over there and think you knew everything you needed to know,” he said.

In the weeks before he flew to Baghdad, he said he had read everything he could find about the Iraqi economy. There wasn’t much.

When he arrived in Iraq, Foote discovered that getting a sense of Iraq’s market was no easier once he was on the ground.

When Foote was in Baghdad, the economists spent most of their time in the secure Green Zone or shuttling between meetings at the old Central Bank—the new one was in ruins—or the Ministry of Finance.

“I often wanted to know, if you had some shopkeeper or some small businessperson, how much government regulation did he face, how many bribes did he have to pay...those basic meat and potatoes issues about how business actually works,” Foote said.

Other Americans might have had the language skills or the cultural competence to feel comfortable going out into Baghdad on their own, Foote said, but he didn’t.

And there was only so much he could learn from talking to his Iraqi translators or to the high-powered businesspeople who networked inside the Green Zone.

He found his lack of contact with ordinary Iraqis both “frustrating” and “sad.”

There weren’t even any reliable government statistics to look at, Foote said, because Saddam’s regime had provided few incentives to compile accurate economic data.

The bottom line, Foote and three of his colleagues wrote in a 2004 paper summarizing their work in Iraq, was that they were forced to operate “virtually blind.”

GAINING WEIGHT

One of the strangest things about that summer by the Tigris, Foote said, was that it wasn’t really strange at all.

American officials eating in the Coalition Provisional Authority’s cafeteria gained weight from all the hamburgers, hot dogs and fried chicken, the economist said.

Inside the Green Zone, suit-clad economists and businesspeople met in air-conditioned rooms to go over PowerPoint presentations.

Foote said he didn’t exactly have to adjust to Iraqi culture.

“At the bottom line,” Foote said of the Iraqis he met, “they were just like every other businessperson, who were trying to raise revenue and reduce cost.”

Foote said he spent much of his time organizing presentations to convince Iraqis who were used to government control that a free market and free trade would ultimately be to their advantage.

His most frightening moment came when he and two of his colleagues had to decide where to set the exchange rate between the Swiss dinar, used in the north of the country, and the Saddam dinar in the south.

They were trying to create a unified national currency, but if they got the exchange rate wrong, it might trigger a recession, Foote said.

There was no fixed guideline for them to follow. They just had to get the number right.

The success of the exchange rate, Foote said, was probably his greatest contribution.

But Foote said that he saw evidence of the lack of proper planning that has been widely criticized.

He said the initial group the administration had sent to Baghdad included no transition economists.

In those crucial first months, Foote said, there was no one on the team who had on-the-ground experience from Eastern Europe or Latin America in transitioning a state-run economy to a free market model.

LOOKING OVER BAGHDAD

Foote, a lanky man known to wear a Boston Red Sox cap, comes across as grounded and well-meaning. He is careful not to make his role in the economic reconstruction seem like a biggger deal than it really was.

During his first months in Iraq, Foote wrote in a Federal Reserve Board essay about that summer, he felt pretty safe. Part of it, he wrote, was his “native Midwestern trust.”

“I’m an economist, not a soldier,” he wrote. “I came to help Iraq’s economy get moving. Why would anyone want to hurt me?”

The second time he visited Iraq, in January and February 2004, the security situation had worsened. One of his economists friends had been injured in a bombing. The mood was increasingly grim.

Foote has not been back to Iraq since 2004. By now, he said, he has lost touch with the state of the its economy. He has moved on to other projects. The most he will engage with Iraq is when he uses its economic transition as a test case for his Economics 1010b course later this semester.

But Foote still remembers what it felt like to gaze over Baghdad from the window of his ninth-floor room. Coming back from each long day of work, he would find the panorama of the city stretched before him. Staring at it, he said, he would try to imagine what the workers on the ground were thinking, what the shopkeepers were worried about that day.

Sometimes, he wrote in the Federal Reserve Board essay, the electricity in his hotel would shut off.

It gave him a chance, he wrote, to gauge the city’s progress from afar—how many neighborhoods were dark, how many had stayed alight.

—Staff writer Lois E. Beckett can be reached at lbeckett@fas.harvard.edu.

For comprehensive coverage of the Iraq War's impact at Harvard five years later, check out The Crimson's

Iraq Supplement.

Read more in News

Lincoln Day Dinner Sees Record Crowd