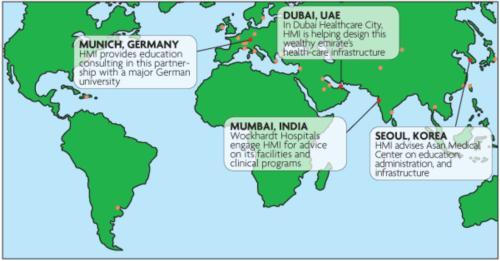

Harvard Medical International footprint can be found in 30 countries on five continents, from Dubai to Dresden and Buenos Aires to Bangkok

See part two, With House Divided, HMI Spun Off

When Harvard Medical School was strapped for cash in the early 1990s, its leaders were earnestly searching for ways to bring in more money.

Seeking to capitalize on Harvard’s health-care expertise, the Medical School’s deans envisioned a non-profit subsidiary designed to “find pockets around the world” that needed medical education advice and had the “capacity to pay,” according to former Dean Daniel C. Tosteson ’46, under whose tenure the organization was created.

Today, the organization—Harvard Medical International (HMI)—operates in over 30 countries on five continents, providing consulting services and bestowing Harvard’s imprimatur on medical schools and hospitals from Dubai to Dresden. In exchange, the non-profit funnels its excess revenue back to Harvard Medical School (HMS), which pocketed over $1.5 million in the year ending June 2006, according to tax filings.

But the drift in HMI’s mission—from an organization principally concerned with medical education and research to one focused on health-care delivery—began to draw heated criticism from University administrators. Leaders in Mass. Hall frowned on the sprawling nature of HMI’s operations, expressing concerns that the organization’s activities fell outside of the Medical School’s “core missions.”

Eventually, these critics, chief among them Provost Steven E. Hyman and Vice Provost for International Affairs Jorge I. Dominguez, got their way.

In mid-March, after years of review, Harvard plans to spin-off HMI’s health-care consulting functions to Partners HealthCare, the Massachusetts health-care delivery group that operates two prominent Harvard-affiliated hospitals—Brigham and Women’s and Mass. General.

But the decision to transfer much of HMI was far from a consensus. And the Medical School officials who were responsible for the organization’s creation and growth—and who have been succeeded by leaders more amenable to Mass. Hall’s perspective—worry that the University will dismantle in a matter of months the “good work” that took over a decade to build.

“I don’t like it at all,” Tosteson says of the impending split. “There are a number of people who are confused about what the intentions of the School are, and I think [Medical School Dean Jeffrey S. Flier] is aware of that.”

TWO BIRDS WITH ONE STONE

HMI, which has grown into a profitable, $21-million-a-year organization, was created in 1994, a time when the Medical School was “really rather poor,” according to Tosteson.

“The Medical School as a whole was under-funded, and we had a high interest in identifying new resources,” Tosteson said.

At the same time, the Medical School was looking to expand its reach into the nascent field of global health.

While individual professors had been consulting in Sri Lanka, South Korea, and South Africa, institutional support and funding were lacking.

“These exercises [of international import] all had one thing in common,” Tosteson says. “They were under-funded.”

So the dean and a couple of his deputies—including S. James Adelstein, who was serving as executive dean for academic programs—developed a plan to kill two birds with one stone: provide a framework for Medical School programs abroad while using the programs to improve the School’s fiscal situation.

Tosteson approached the Harvard Corporation, the University’s top governing body, to propose a subsidiary that would concentrate the Medical School’s international efforts and draw on the expertise of the world’s most prominent medical school.

At its inception, HMI focused on consulting for medical education at foreign universities such as Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat in Munich.

“[There’s] no question that it started off as a means of helping institutions with their educational endeavors—sending people over and giving them advice on how to do it,” Adelstein said.

But beyond education and research lay a burgeoning market for health-care consulting, and HMI steadily stepped in to meet that lucrative demand.

MISSION DRIFT?

The Mass. Hall leaders who championed the break between the Medical School and HMI’s health-care consulting divisions insisted that an organization using Harvard’s name should limit its purview to education and research.

But the sort of work these officials thought Harvard had no business in—designing regulatory frameworks, augmenting patient safety, and improving the performance of health-care systems—was now providing an increasing share of its revenues.

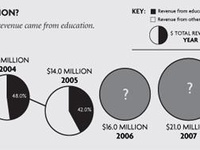

In 2005, the last year for which HMI publicly reported its revenue sources, health-systems consulting surpassed education as a source of funds.

“The change was slow and gradual,” Hyman, the provost, writes in an e-mailed statement. “Over time a number of faculty and members of the administration recognized that major aspects of HMI’s effort were moving away from the University’s core mission.”

But HMI’s founders insist that the organization’s charter is far broader than education and research.

According to Robert K. Crone, who led HMI from 1995 until last year, the subsidiary was explicitly charged by the University with “sharing medical and technological know-how” and advising on “administrative and management functions.” (The Corporation did make clear, however, that it did not want HMI “to become directly responsible for the management of health care facilities.”)

HMI’s leaders argue that the organization’s move into health-care consulting followed the changing market.

“HMI didn’t create the trend; it responded to the trend,” said George E. Thibault, a former HMI Board Member. “There was always an important educational component, but it got to be a smaller percentage of the activity and a smaller percentage of the revenue than health-care delivery and consulting.”

But the changing nature of HMI’s activities didn’t draw the ire of Mass. Hall because HMI had a friend in high places during its banner years.

“Under President Summers,” Crone writes, “central administration positions were removed from HMI’s Board.”

Instead, according to the former HMI chief, the dean of the Medical School—who also chairs the board of the HMI—“went directly to President Summers to seek approval on any large scale initiatives.”

And Summers, for his part, readily gave his stamp of approval to a slew of projects, “explicitly supporting” HMI’s expansion, according to Crone.

THE HEADY DAYS

In January 2003, Phyathai Hospitals in Bangkok, Thailand signed on with HMI to “embark on a long-term partnership” to focus on clinical services, education, and management across its hospital network. And later that year, HMI announced it would help Wockhardt Hospitals—a chain of specialty hospitals across India—“create a sustainable quality improvement model.”

But the crowning accomplishment—and the embodiment of HMI’s mission gone awry to Mass. Hall leaders—was Dubai Healthcare City, the headline-grabbing agreement between the Emirate and Harvard that the parties inked in 2003.

HMI is now helping to build the city’s health-care infrastructure from the ground up, creating systems that draw on over 400 health-care professionals. And all of this comes while the project is expanding to 20 million square feet with HMI’s assistance.

As the percentage of revenue coming from educational projects drops—from 63 percent to 42 percent between 2001 and 2005—HMI has seen its total revenues skyrocket from just over $8 million in 2001 to nearly $21 million today.

HMI’s swelling coffers soon put the organization—which spent its first seven years repaying its foundational loan from the University—into the black, allowing it to begin transferring millions of dollars to the Medical School.

But when Summers was forced from office in 2006, HMI suddenly found itself without a champion in Mass. Hall.

The new leadership viewed HMI’s activities with growing unease, fearing it had already crossed the Rubicon and was stamping Harvard’s seal on institutions around the globe with little relation to the Medical School.

“HMI had become principally a consulting company,” said Dominguez, the vice provost. “It did no research. It did not support research.”

—Staff writer Clifford M. Marks can be reached at cmarks@fas.harvard.edu.

—Staff writer Nathan C. Strauss can be reached at strauss@fas.harvard.edu.

Multimedia

Read more in News

Lincoln Day Dinner Sees Record Crowd