Billy hangs high on the wall of Cabot Dining Hall. The framed photo focuses on his gaping mouth, out of which rolls a thick red tongue pierced by a full-sized steel fork. A makeshift title cut from a newspaper—the superlative, “Most Likely to...SUBVERT THE SYSTEM”—accompanies the picture.

A petite dining hall worker clutches her hands to her chest and gazes up at the picture affectionately. “That’s my Billy!”

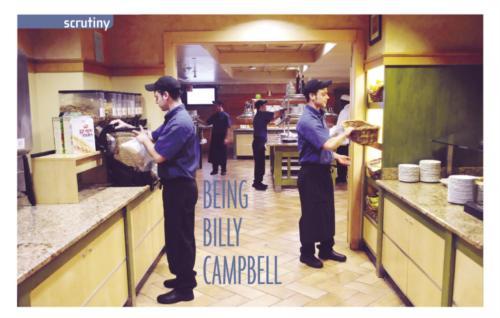

The 27-year-old busboy saunters over, black cap flippantly propped on his thinning dark hair.

“Some student was taking a photography class, and he just came in and took a couple pictures of me,” he says. “So I stuck a fork through my tongue.”

The day after his eighteenth birthday, Billy got his tongue pierced. Over the years, he’s stretched out the hole to its present size—capable of accommodating a fork. To demonstrate how he did this, he deftly pushes his tongue about in his mouth and pops out two thick metal stems. He then easily slips his index finger through the fleshy chasm. He wiggles it.

According to Billy, the student photographer sneaked into Cabot’s serving area one night and replaced the frame’s rustic image—it used to be a pitcher of water—with Billy’s demonic likeness.

A few of Billy’s older female coworkers congregate below the picture and giggle furtively. Though the picture swap occurred a few years ago, management still hasn’t realized it, they say.

Ever since Billy—more formally, William A. Campbell III—began working for Harvard University Dining Services a bit over a decade ago, Cabot Dining Hall has never been quite the same. He willingly tests the limits, mostly for his own amusement, and he’s not too sure where he’s headed—and he may not even really care.

“I don’t really put myself out for huge goals,” he says. “I don’t put much thought process into it.”

If Billy isn’t hunched over, pushing around cartons of glass cups, or standing outside on a cigarette break, he drifts about the dining hall with eyes languorously half-shut.

ID swiper Mary A. Quinlan sits by the swipe machine and titters, amused at the thought of finding Billy in the dining hall. “He’s wandering,” she says. “Not aimlessly. But he’s wandering.”

Billy wears the familiar garb of a HUDS employee: a black apron wrapped around his hips and a garish blue top with his first name inscribed in cursive. A pack of Newport—the only brand he smokes—is tucked into his breast pocket.

At 27, Billy has the face of a battered musician: large bright brown eyes that contrast with the dark shadows underneath and a malleable mouth that changes fluidly from an unassuming smile to a weary smirk. But something about him is not quite ready to age. He’s rakishly handsome, and the dark brooding on his face is the product of a bored amusement with the world around him—a youthful-yet-jaded curiosity that probably does more harm to himself than to others. He initially gives off an impression of complete carelessness, uttering “whatever” whenever he has gone over the allotted time for his lunch break.

“I’m kinda the guy that rolls with it whether it’s bad or good,” Billy says. “I don’t like things affecting me too much. I either ignore it or try to block it out.”

Billy became a HUDS employee at an age most of his peers were going to college. He is often mistaken for a Harvard student who happens to be working for HUDS, and despite the non-fraternization rule in the HUDS code of conduct, he enjoys a generational camaraderie with his fellow 20-somethings.

When Billy was 16, his mother, who works at Harvard Business School, was told of an open position with HUDS. So Billy quit his minimum-wage cashier position at the grocery store Stop & Shop and began working at HUDS one or two days a week. After being officially hired, he worked in the Cabot and Pforzheimer washrooms and then the Currier dishroom.

“The first couple years here, I worked in the back,” Billy says. “I hardly got to see the students. I got to see their dishes.”

In 2000, Billy received an authorized position in the Cabot dishroom; after two years, he claimed a busboy position.

Nowadays, he arrives at 11:15 a.m. on weekdays, punches in the time clock, and roams about in the “Outer J”—a term coined by Billy to refer to the outer part of the Cabot servery—to check and refill the cereals, beverages, yogurt machines, ice machines, trays, and silverware. In addition to restocking throughout the day, Billy cleans the counters, mops the floors, and acts as the neighborhood nutritionist, preventing one allergy attack at a time.

“I answer questions about food: ‘Does this have nuts in it?’ Yes or no,” he says.

Billy has little to complain about when it comes to his job. He enjoys the benefits of being an employee of Harvard, he says, including good medical coverage, decent dental coverage, stock options, paid-leave for short-term injuries, and even classes about money management.

The company is nice too—he hangs out with a few of his coworkers, including an acquaintance from the second grade, outside the workplace.

“I’ve had issues with prior management and stuff like that, but you never know who you’re going to rub the wrong way,” he says. “I get along with a majority of my coworkers.”

Though Billy ends work at 8:15 p.m., he often stays later to take part in Cabot activities—one of the best things about his work life, he says. After initially brushing off a student’s encouragement a few years ago to participate in the House musicals, Billy remembers thinking, “What am I doing tonight? Nothing? Well, I guess I’ll try it.”

What followed was a bizarrely “random” experience. He played minor roles in “Guys and Dolls” and “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,” and found himself dancing and singing on stage, complete with jazz hands and frantic attempts to remember lines.

“The more fearful thing for me was messing up a line that would mess somebody else’s lines up.” Otherwise, he didn’t experience much stage fright. “I’ve obviously messed up in public before,” he says ruefully.

While Billy the choir boy took the stage about five years ago and never returned, Billy the athlete still participates in House life as a seasoned forward on Cabot’s IM hockey team.

“You get to hang out with your coworkers—plus, you get to meet students outside the dining hall environment,” Billy says of his experience playing hockey. “You can actually be like, ‘Hey, what’s up. Good play out there.’ You can’t really say ‘Nice goal’ when somebody’s grabbing a glass.”

Billy pauses when he’s asked if he has ever been to a room party in Cabot.

“No.”

He rolls his eyes. Though his eyes and eyebrows are the most animated features of his face, their hyperactivity is usually a sign that he is concealing information. In fact, what Billy says is often negated by what he does with his eyes.

Example: How’s the food at Cabot?

“It’s great. It’s fantastic. Sustainability all the way.” His voice remains flat as his eyebrows do a little jump.

“He’s a beast,” says Mary, the ID swiper who has known Billy since he started working for HUDS. “He’s witty beyond words. I’m more serious than him, but we enjoy life’s ironies.”

His lack of seriousness sometimes gives Billy a bad reputation, Mary says, but she loves his quick wit, which often elicits moments of “You’re not going to believe what Billy said today” from other dining hall staff. She often finds banana stickers plastered onto her clothing—Billy’s doing, of course.

Despite his good humor, Mary’s most striking memory of Billy is not funny at all. When her husband passed away, Mary needed the lyrics of “Oh Danny Boy” for distribution at the funeral. Unprompted, Billy printed out the lyrics and handed them to her.

“You know, I really feel my life is richer because he’s in it,” she says.

Mary says many people wave Billy off as a playboy, (“I guess he qualifies,” she says in a brief moment of reconsideration), “but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t love people.”

Billy currently lives in Malden, Mass. with his girlfriend and their three-month-old son. Every time William IV comes up in conversation, Billy’s eyes shift unsteadily. He is still unsure whether to call this son—who arrived in his life on July 29—a “he” or an “it.” But he does know some things: “Well, you know...” Billy trails off. “He’s a baby. He sleeps, eats, craps.”

“It’s been interesting,” he says. “There’s some saying: a mother’s a mother as soon as she’s pregnant, but a father’s not a father until he sees his child.” Billy says he did not “feel that whole feeling” until he was standing in the delivery room [of Melrose-Wakefield Hospital hospital] at 5:56 a.m., slightly inebriated and dressed in a hospital smock.

Billy gives a quick debriefing of his ten-month relationship with his significant other: they were just friends prior to the pregnancy, and the pair decided to live together for the sake of their child.

“We don’t dislike each other,” Billy says. “I guess we’re girlfriend-boyfriend.”

Though he wishes he had been more financially secure before his son’s birth, Billy has come to accept the challenges and sacrifices that come with fatherhood.

“My life outside of work changed a lot since I got a kid. Before my son, I used to go to a lot of parties and bars,” Billy says. “You just see something that has no choice and you want to do what’s best for him.”

Indeed, the former raver and passionate mosher (“I’d always look for the tallest dude I could find and have him throw me up in the air—sometimes you get caught, sometimes you don’t”) has set aside the raucous rhythms of Linkin Park, Korn, and Ozzy for the sobering sounds of a crying baby.

“You don’t have the ability to stay up anymore,” Billy says. If he were to continue pursuing his passion for the local bar scene, he says, “I wouldn’t be doing my other responsibilities.”

Billy hopes to finish his training as an HVAC/Refrigeration repairman, perhaps taking courses after an early morning shift at the dining hall. He wants to keep working for Harvard—whether for dining services or Facilities Maintenance Operations.

“I tend to have these good ideas and not do anything about them,” Billy says. “But I think I have more motivation now than ever.”

This past summer, Billy earned his high school diploma through the Bridge to Learning and Literacy Program @ Harvard, an education program for Harvard’s hourly employees. Though he had never strongly considered getting his diploma, the option was readily available through Harvard, and he decided he wanted to “have the option in my life” to pursue other courses that might require a GED.

Billy has been a breadwinner for his family since high school, ever since his father was forced to retire after several accidents (including a collision with a moving bus) left him with seven broken vertebrates. Born in Methuen, Mass. near the New Hampshire border, Billy lived most of his life in Medford, a few miles north of Harvard, with his parents and older sister Krystal.

“Low-middle-class-family type deal,” Billy says. “High poverty level or something like that.”

Though shouldering adult responsibilities, Billy did not always display model behavior.

In elementary school, the class clown was so repulsed by the idea of remaining seated that he took strolls around the classroom during test time, becoming every teacher’s nightmare.

“I never liked school. I was never a big studier,” Billy says. He was diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder at the age of eight and had reading problems for years. “They said it was dyslexia, but I think I just had trouble with blending words together—phonics type things," Billy says. “I’m still a horrible speller.”

The classes he did enjoy included physical education, “recess,” and mythology: “Stuff that wasn’t actually real were the classes I tended to do really well in.”

Billy describes his younger self as “very imaginative,” whiling his time away with baseball, hockey, videogames, and occasionally fishing—at least when he had the patience. He relished ideas that “didn’t really make much sense, but made sense to myself,” and to this day, he still has affection for the hypothetical—the underlying possibilities of a world that seems depressingly clear-cut for most.

“I always wonder what puts that desire in people to go about these certain rules and not question it,” he says. “If somebody tells me something, I have to ask why. I have a really hard time to not answer back, going with the flow when it comes to set things.”

Such a belief system has brought Billy some trouble. As he recounts his high school years, it sounds like a long list of expulsions: he began in vocational school as a freshman but was asked to leave during his junior year for behavioral issues. At his new public high school, the 17 year-old dated a 15 year-old girl, making sex between the two illegal in Massachusetts. “I guess you can say we were active and her mother found out,” he says.

Under a restraining order, he left the school after three months and transferred to an alternative school for students with behavioral issues, and a school which he quickly dropped out of. “They were teaching me fractions my junior year of high school. I knew it was a bad school because I started getting straight A’s.”

To Billy, attendance was optional. “I’d get up in the morning and get ready for school and just take the wrong bus,” he says. “You ever see those freaky kids who hang out in Harvard Square? It’s what I kinda did.”

Around the age of 14, the former bully (“You didn’t really care how you affected other people”) began talking to his former victims. After an encounter on the bus that piqued his curiosity, Billy began to hang out in the “Pit” in the Square with people not at all like him.

“Maybe I just misjudged a lot of things I used to,” Billy remembers thinking. He had been raised to subscribe to a certain set of beliefs, but these newfound friends challenged his upbringing. He met individuals with severe drug addictions and alcoholism, and he also encountered a homosexual man for the first time—the very type of person he and his friends used to victimize.

“You just get different perspectives,” Billy says. “Things that were so pushed away are actually fine.”

But the mingling and the experiential expansion of the Pit are long gone.

“Most of them are dead,” Billy says.

“I liked to bug people, probably just to get attention. I’d find it funny when I got in trouble,” Billy says. “I pretty much do whatever to see it. I guess I do things out of boredom.”

Boredom coupled with a constant desire to question existing structures has made Billy an inquisitive sadist. He likes “to think about what would happen if something was to happen that definitely would never happen—if something in someone’s personality goes completely out of the way.” He poses a hypothetical situation: under the influence of an “angry” person, a “nice, wholesome” individual loses his former personality and becomes “completely insane.”

“It’d be great. I would love to see that,” Billy says. This is the most excited he has looked all week. “I dunno if that’s sick.”

So he’s a fan of subversion? Corrupting the innocence of others?

“Well, then, you could take the very angry person and make them nice,” he reasons.

Billy likes answers that can be questioned and people that can be changed. A self-described atheist (“You die, you live. That’s about it”), he finds religion a particularly interesting example of a set of beliefs that people are drawn to for reasons he would like to understand.

“I kinda like seeing how their mood gets when you ask these questions. You’ll see some people being really honest. And when you question some other people, they seem to get this intense face of anger of ‘Why would you do that?’ I feel it’s a simple question.”

Billy doesn’t hate or rag, and besides those who never return his lighter (his one pet peeve), he likes “more or less everybody” because “everybody has something different to offer.” But regardless of the person, he always wants to know how someone has come to his or her respective conclusions. “I just like to know why,” he says.

Nothing is ever as simple as it looks, and an answer will probably lead to another question. The people we meet and immediately judge, the moments we parse through with painstaking afterthought, the rituals we abide by for no clear-cut reason—why do these things happen, and what do they reveal about our characters? These are things Billy wants to know—he certainly doesn’t think he understands anymore than the person next to him. Rarely does a sentence pass through Billy’s lips unaccompanied by an expression of self-doubt; he punctures his speech with phrases like “I dunno,” “I guess,” and “more or less.”

What he does know is that “regardless of where you are or what you’re doing, you wake up and something interesting could happen in the day.” The world is unknown—therefore, there must be something to be found.

When Billy was five, he wanted to be an astronaut. “I had no idea why. I just thought it’d be really cool to jump really high in space,” he says. Two years later, he clambered up a tree until he found himself teetering on a branch 50 feet from the ground.

“I just fell and I hit the ground. I was scared but not much you could do when you’re falling.” He shrugs.

And maybe that’s the way it’s always been for Billy.