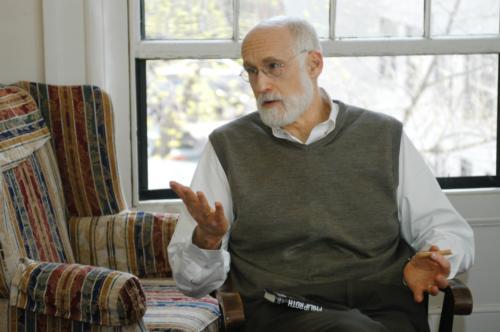

At 6’5 with a white beard reminiscent of Socrates’, Jerome E. Groopman certainly looks the part of the wise old doctor. TV show host Stephen Colbert once even accused him of “trying to look like God.”

But in his new book, “How Doctors Think,” this Harvard physician, professor, and author conveys a message very much at odds with his deified image: “Doctors desperately need patients to help them think.”

Groopman’s book considers how doctors diagnose, a question that first grabbed his attention when he discovered he was at a loss to teach his medical students how to think as doctors.

The hardcover made number three on the New York Times bestseller list and has stayed in the top 10 ever since.

But even in the midst of taping interviews with “The Early Show” and NPR, Groopman, the Recanati professor of medicine, still finds time to engage with undergraduates in his weekly freshman seminar, “Insights from Narratives of Illness.”

His book’s release and unconventional ideas come as the Harvard Medical School (HMS) reforms its curriculum, and as the doctors around the country debate how best to improve medical care.

“I realized I didn’t know why or how I thought successfully, and why and how there were times when I didn’t think well,” Groopman says. ”That was the genesis of the book.”

DIAGNOSING MISDIAGNOSIS

Though the public may have bought into Groopman’s framework for medical diagnosis, not everyone in the medical community agrees with his emphasis on psychology.

“It’s tempting to think of [medical care] as something that’s just doctors sitting around and thinking,” says Darshak M. Sanghavi ’92, another physician author who earlier crossed swords with Groopman in an online debate on Slate.com. “But I think we need to be a little more creative than focusing primarily on the thinking of doctors.”

In the book, Groopman recounts cases of brilliant success and terrible failure, weaving in analysis of the psychological shortcuts he says doctors use to make a diagnosis.

The author writes that doctors need to be careful of their own cognitive biases, such as a predisposition to diagnose an illness recently seen or to stereotype patients in order to reach a diagnosis.

He uses the example of one middle-aged woman, whose physicians assumed that her severe headaches and hot flashes stemmed from menopause.

In Groopman’s retelling, the sixth doctor saves the day by questioning the simple diagnosis, discovering that the symptoms were the result of an unlikely culprit: a tumor.

Groopman argues that patients can play a crucial role in preventing their doctors from too readily trusting these biases.

“For me as a physician to think effectively, I need you, as a patient, to help me,” he says. “If these shortcuts are leading me astray, and you can somehow know about that, you can get me back on track.”

PATIENT FRUSTRATION

On a recent afternoon, Groopman discussed his book in the Freshman Seminar Office, where he teaches his class. During the interview, Groopman lay down to rest his injured back, a reminder that the doctor himself has experienced life from the other side of the stethoscope.

In the book, Groopman doesn’t shy away from his own experiences, devoting a chapter to his protracted search for an explanation of his debilitating hand pain. Groopman chronicles his circuitous journey from doctor to doctor, including a year spent seeing one physician, who he claims fabricated a diagnosis.

A former student remembered hearing Groopman’s stories of patient frustration.

“That’s what made him want to sort of demystify the thinking process of doctors for patients,” says Aviva J. Gilbert ’07, a former seminar student who still communicates regularly with Groopman. “If you can, as a patient as educated as he is, get such a variety of opinions, what you really want to know is how did they come up with those opinions.”

A MEDICAL DEBATE

“How Doctors Think” adds fuel to an ongoing debate about reforming health care and medical education.

During the Slate.com debate, Groopman and Sanghavi found themselves at odds over the best way to teach diagnosis.

According to Sanghavi, Groopman’s prescription for improving medical care is too individualistic.

“In my opinion, the biggest problem isn’t that we standardize, it’s that we don’t do it enough,” Sanghavi says.

But Groopman insists that doctors need to learn more about avoiding cognitive traps, and not simply rely on systematic changes, such as computerizing prescriptions or installing hand sanitizer dispensers.

“There’s this huge gap in medical education,” Groopman says. “This is a whole new dimension that hasn’t really been addressed.”

The debate on how to train young doctors comes as HMS reforms its decades-old curriculum. According to Jules L. Dienstag, the dean for medical education, Groopman’s ideas are playing a role in changing the school’s approach.

“Fortunately for us, Dr. Groopman is on our faculty, and the dialogue he has initiated resonates strongly among many of our faculty and faculty leaders,” Dienstag writes in an e-mailed statement.

He also notes that Groopman once proposed a course in cognitive psychology and clinical reasoning.

Sanjiv Chopra, Harvard’s faculty dean for continuing education, says he’s interested in incorporating cognitive psychology into courses for practicing doctors as well, though none is currently devoted to the subject.

“I’d like to talk to him and meet with him and pursue this further,” Chopra says. “I think it’s a great idea.”

TEACHER, M.D.

Despite his recent success in publishing, Groopman continues to his undergraduate seminar course every Thursday to rave reviews from pre-meds and bibliophiles taking the course.

“Every person that I’ve talked to has been very happy with the class,” says current seminar student Daniel Holleb ’10. “He sort of has something for everybody.”

Groopman gave all his students copies of the book, which he recently added to the syllabus.

“I wasn’t going to make them buy it on their own,” he chuckles.

In keeping with the seminar format, the generosity has run in both directions. Before he faced the cameras to publicize “How Doctors Think,” Groopman’s students made sure to give him some press tips.

“He got a lot of advice on how to deal with Colbert, because he’s kind of aggressive,” Lily J. Durwood ’10 says. “But I think he ended up doing a pretty good job.”

—Staff writer Clifford M. Marks can be reached at cmarks@fas.harvard.edu.

Read more in News

Law School Students Protest Abortion Decision