The Institute of Contemporary Art opens its brilliant new building, designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, to the public this Sunday.

Two weeks before Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) was initially scheduled to open on Sept.17, 2006 with its celebratory parties already planned, the opening date was postponed indefinitely.

Construction setbacks and permit disputes meant that the public would have to wait nearly three months to see the finished museum; yet viewing the stunning result, one wonders why nothing like the ICA happened until now.

This Sunday, the most architecturally interesting building in Boston will open its doors. It is Boston’s first new art museum since the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) opened at its current location on Huntington Ave. in 1909.

Not only has there been a dearth of new cultural institutions in Boston, there has been little critically acclaimed architecture here in the 30 years since the construction of I.M. Pei’s John Hancock Tower—an iconic building, but an engineering disaster.

This trend is on the verge of reversal, however, with major expansion projects underway at the MFA, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and Harvard’s own Fogg Museum, bringing projects by superstar architects Norman Foster and Renzo Piano to Boston for the first time

But if there are several developments on the horizon, the ICA is the crown jewel in the city’s architectural tiara. Many in the art world have high hopes that the new Institute will play a major role in turning Boston into a significant destination in the contemporary art world.

The ICA, designed by New York-based architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro, is both a strikingly beautiful building and the celebrated avant-garde design team’s first undertaking in the United States.

The glass-clad structure thrusts over Boston Harbor, the top floor firmly cantilevered 80 feet beyond the building’s footprint, above a harbor-side promenade. The traditional neoclassical museum entrance is inverted: two sweeping sets of steps rise from the open water to meet the museum, but imposing marble is replaced by warm wood and they are better suited to picnics than processions.

When completed, the promenade should stretch the length of the harbor, though currently only the section adjacent to the museum is finished. Underneath the massive cantilever, the space is not cavernous, as it threatens to be when seen from afar, but intimate—an effect achieved through the repeated use of wood planking to cover the promenade, the steps, and the underside of the overhang.

The museum’s actual entrance is warmly welcoming rather than imposing; one tall triangular wall is devoted to a commissioned mural, due to rotate each year. Currently on view is Chiho Aoshima’s whimsical “The Divine Gas,” which manages to turn an image of a girl passing gas into a dainty, stylized, and oddly compelling work.

The museum includes a gorgeous theater as well as educational rooms, but these are secondary organs to the gallery space—the real focus of the building’s mission.

The galleries are floored with large, polished concrete slabs, the grid mirrored by the skylit paneled ceiling. During a tour of the galleries, one of the architects—Elizabeth Diller—said that she was trying to deal with “the architect as protagonist versus serving as background. We’ve tried to make the architecture a partner to the art.” The architecture isn’t meant to be ignored, and while it certainly complements some of the larger, more powerful pieces, it tends to overwhelm the more delicate works.

As the weather changes outside, the experience within ICA will also change, to an extent surpassed only by the recently reopened L’Orangerie in Paris, where Monet’s water lilies are in a constant state of flux due to changes in the natural light. This environmental variable suggests a throwback to the pre-modern era, but is a welcome incongruity in an otherwise fully 21st century building: a reminder that a new museum is not only a chance to see new art, but also a chance to reevaluate the way in which we experience art.

Just as the galleries become closely linked to the weather through the skylights, the entire building is deeply connected to the harbor over which it looks. Riding up the 50-person glass elevator, the view of the water is constantly changing yet always intriguing. No part of the museum expresses this connection better than the unfortunately named Mediatheque, which hangs angled below the cantilevered galleries.

The Mediatheque is a computer lab in which to explore the ICA’s collection and online activities. The computers are arranged sloping downwards, mimicking both the theater and the grandstand below. The front wall of the room is one large plate of glass, framing a constantly changing and eternally hypnotic portion of the water and eliminating the external context of a horizon.

It is important to remember that this is a small to medium sized museum. New York’s Museum of Modern Art is ten times larger in terms of square footage; the ICA has barely 18,000 square feet of gallery space, leaving hardly any room for future expansion.

“We admittedly have limited gallery space, but we hope that the curatorial creativity will make up for it,” said Paul A. Buttenwieser ’60, chair of the board of trustees. “Everybody wishes they had more space.”

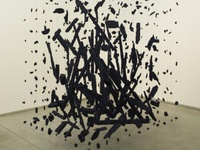

The ICA has only recently become a collecting institution. “If we had collected since the beginning, we would have an amazing collection of 20th century art,” Buttenwieser said. The permanent collection has 29 pieces so far. Most is of high quality, with a few truly exceptional pieces like Josiah McElheny’s “Czech Modernism Morrored and Reflected Infinitely,” and Cornelia Parker’s “Handing Fire (Suspended Arson).” The current special exhibition, “Super Vision,” presents an all-star cast of artists and is an appropriate inaugural show for a museum that explores the depth and future of vision and art.

Currently, the ICA is surrounded by acres of parking lots—the windshields of the cars oddly mirroring the glass-paneled jewel-box of a museum. Plans are afoot for a massive waterfront redevelopment, including offices, residences and hotels.

Much more interesting, and important, is Boston’s cultural development. What has always been a sophisticated and cosmopolitan city is now poised to fully embrace the contemporary.

—Staff Writer Alexander B. Fabry can be reached at fabry@fas.harvard.edu

Read more in Arts

Steve Martin and the Lapin Agile