More than 70 students, scholars, and community members gathered inside the Barker Center to celebrate Native American traditions and to address concerns facing New England’s indigenous tribes last night.

While they feasted on traditional Native American fare such as cornbread and baked beans, and while some attendees sang music of the local Wampanoag tribe, the assessment of modern-day indigenous life in the region wasn’t entirely upbeat.

“There’s not a thing that our people haven’t gone through in the 350 years since the invaders came,” said Tall Oak Weeden, an historian, activist, and elder in the Wampanoag-Pequot tribe.

Weeden came dressed in a U.S. flag, but he acknowledged the contradictions in his attire. “If you knew the truth, you would never wear this flag because it’s stained by our blood,” he said.

Weeden was one of four members of the panel, “Native New England Now: Tribal Leadership in 2007,” who spoke at the event.

The location at the edge of Harvard Yard was itself historic—more than three and a half centuries ago, Harvard built the brick Indian College on the other side of the Yard, at present-day Matthews Hall, to aid in “the education of English and Indian youth.”

The one Native American who graduated from the original Indian College before it shut down was a Wampanoag tribe member.

And one aim of last night’s panel was to reconnect with Harvard’s indigenous past.

“The most basic thing is to honor the premises under which you were founded,” panelist Melissa Tantaquidgeon Zobel, the Mohegan tribal historian, told the audience.

Zobel emphasized the importance of teaching Native American history at universities.

Her remarks came at a time that Harvard is expanding its indigenous history offerings. Assistant Professor of History Malinda Maynor Lowery, who joined the Faculty last year, offers three courses studying Native Americans of the past and present.

Zobel said that Harvard’s new offerings mark a step forward from a previous era in which Native American studies were confined to other departments such as anthropology but lacked a place in many history course catalogues.

A third panelist, Carol Jean Palavra, an elder of the Nipmuc Nation, said that the study of Native American history was key to creating and maintaining unity among members of the indigenous community.

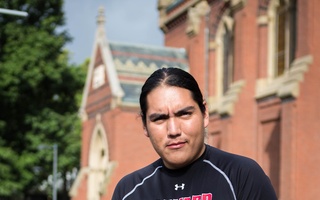

And the theme of reconnecting with one’s roots carried through the remarks of the fourth panelist, Tobias Vanderhoops.

Vanderhoops grew up in Everett, north of Boston, but he belongs to the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head on Martha’s Vineyard. He described how, as a child, he longed for life on his tribe’s island.

“I knew I didn’t really fit in [at Everett] but I knew there was a place I did fit into. All of my life, I would ask my mom when we’d move back to Martha’s Vineyard.”

He returned to the Vineyard as a young adult and quickly rose through the ranks of tribal leadership—he has served on the tribal council since his mid-20s.

Last night’s event culminated the fall programming of “Native Voices, Native Homelands,” a year-long series organized by the Harvard University Native American Program, which runs under the auspices of the Kennedy School of Government.

Read more in News

Software Provides Reading ListsRecommended Articles

-

Indian Tribe Back in YardThe Wampanoag language returned to Harvard this weekend after more than a three-century hiatus, during a conference exploring the complicated

-

Students Celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day

Students Celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day -

Forging A Path for Native American Studies

Forging A Path for Native American Studies -

Pforzheimer House Begins Native American Fellows ProgramThree visiting fellows in Pforzheimer House will lead talks and excursions related to historical and contemporary Native American culture

-

Living the Culture

Living the Culture