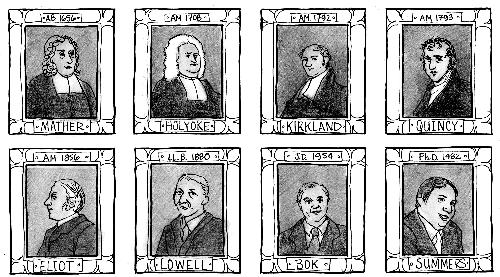

The Fellows of Harvard College have only selected one non-alumnus to be Harvard’s president. The year was 1654, and Harvard was 18 years young, having held its first commencement just 12 years before. But since University of Cambridge alum Charles Chauncy died in office in 1672, Harvard has been led by men holding Harvard degrees for a staggering 334 consecutive years.

As the Presidential Search Committee begins winnowing down a list of thousands of potential candidates to a final selection, this venerable tradition may be in jeopardy. After all, past search committees have looked closely at non-alumi. As recently as 2001, the presumptive favorite and one of four finalists was Lee C. Bollinger, who had no affiliation to Harvard. And past search committees haven’t been afraid to break tradition. The 299-year sequence of presidents who received their bachelor’s degree from Harvard College was snapped in 1971 with the selection of Derek C. Bok.

The tradition of an alum of one of Harvard’s schools governing the University, however, has persisted for a reason. Although there are many qualified candidates who don’t hold Harvard degrees, alums are better suited to lead the University, particularly given the complex situation Harvard finds itself in today. To that end, the Presidential Search Committee should make an effort to continue the tradition of selecting a Harvard man or woman—likely an alum, but possibly a professor—to lead the University.

The job of governing Harvard simply has too steep of a learning curve for someone not acquainted with the ins and outs, quirks, and traditions of the University, even if they have experience at the helm of other institutions of higher education. Harvard’s decentralized structure—famously captured by the phrase “every tub on its own bottom”—is unlike most other universities in the country. Though the president, along with the rest of the Harvard Corporation, sets budgets and priorities, hires deans, and approves all tenure offers, the schools are in many ways independent, self-governing units. This isn’t the case at many other institutions.

One ramification of this structure is that the faculty wields tremendous influence, as illustrated by the uproar that led to the resignation of former President Lawrence H. Summers. At a time when faculty-administration relations have been strained, it will be important to have a president who understands the peculiar balance of power at Harvard.

Harvard is also beholden to tradition. For instance, whereas most Universities have a larger board of directors, many of whom are elected, Harvard continues to use a model conceived of in 1650: a seven-member, self-selecting, and secretive corporation. Other traditions—like final clubs, the house system, and shopping period—apply less to University governance, bust are still part of the zeitgeist of the school that need to be understood before policy is made. These traditions also act as obstacles and create a tremendous amount of inertia. A new president needs to understand them so that he or she can comprehend what can and cannot be changed quickly.

While an outsider may be able to come to understand these traditions and quirks after an ample period of immersion, Harvard’s next president will need to hit the ground running and can’t afford to survey the lay of the land for too long. Before he or she even formally takes office, the new president will need to make one of the most crucial decisions of his or her tenure by selecting a new dean of the Faculty. He or she will also be faced with the prospects of implementing a new College curriculum, jumpstarting a fundraising campaign, and dealing with a faculty that will likely treat him or her with a sense of trepidation. Finally, the next president will have to make critical decisions about the University’s future in Allston right off the bat. If he or she doesn’t fully understand Harvard’s place in Allston—where complex competing interests, tricky town-gown relations, and years of planning make the learning curve particularly steep—Harvard’s expansion across the river could be set back by several years.

All of this will take a tremendous amount of vision, another area in which an alum or professor would have an additional edge. Someone who understands what Harvard has been in the past and how it got to where it is today will have a better idea of what Harvard needs for the future. They will also be well versed in the bold, trend-setting thinking that has dominated Harvard’s history.

A graduate of Harvard may additionally have an easier time connecting with donors and alums in the critical venture of fundraising. “When I was a student here” anecdotes and shared experiences provide an instant connection that an outsider would struggle to forge.

Finally, there is the matter of pride and the tradition itself. Harvard is notorious for thinking of itself as the premier institution of higher education in America, if not the world. Being led by someone who went to some other institution may insult that pride and hit us all in the gut, no matter how wise and learned that new leader might be. At the end of the day, something would not feel right if our president was a Yalie.

That’s not to say that the Search Committee should knock all outsiders completely out of the race. Someone with enough potential could overcome these obstacles given enough time. But an insider—either an alum or a professor—has a big advantage. So don’t be surprised if, upon being introduced to the University, our new president’s first words are “it’s great to be back.”

Adam M. Guren ’08, a Crimson associate editorial chair, is an economics concentrator in Eliot House.

Read more in Opinion

The Ship of Truth