For a writer who made his mark criticizing films with a mixture of dry wit, far-far-out metaphors and opinions that sometimes seem designed to surprise and provoke, Elvis Mitchell is startlingly polite. While taking his film class last year, I visited his office hours in the Carpenter Center’s Sert Café. Interrupting our conversation about comic books, he jumped up, crossed the room and opened the door for a shopping-bag-laden stranger.

This is the guy who, as a film critic for The New York Times, compared Dirty Dancing: Havana Nights to “[A]n episode of ‘American Dreams’ written by Pepe Le Pew.” In a glowing review of Jennifer Garner’s 13 Going on 30 he said that the film “is content to eat its retro snack cake and have it, too.”

In person, Mitchell is neither as surreal nor as opaque as his metaphors. He started our interview by asking me how I was doing, what kinds of classes I was taking and what I wanted to do with my life after I graduated. When not behind a keyboard or podium, he seems to spend more time asking undergraduates to discuss their film opinions than he does talking about his own.

After leaving the Times last spring in a much-discussed shakeup, he has returned to teach his popular film course, Visual and Environmental Studies 173x, “American Film Criticism” this semester. The class offered open enrollment last year to accommodate 107 students. Based on what TFs say was overwhelmingly positive student feedback, it has swelled even further this semester. Also returning is Mitchell’s seminar, African and African American Studies 183, “The African-American Experience in Film: 1930-1970.”

EVERYONE’S A CRITIC...

When I asked Elvis why people seem so interested in him, he chuckled, but feigned total confusion.

“I don’t know,” he said, grinning and shaking his head. “What do you think?”

I was caught off-guard. I suggested it had to do with his writing style, which had pushed the Times’ boundaries and sharply separated him from his peers, A.O. Scott and Stephen Holden.

He just shrugged.

This relaxed attitude toward his inherent different-ness may have been responsible for making Mitchell a point of discussion on campus, as well as in the larger worlds of the media and movie industries.

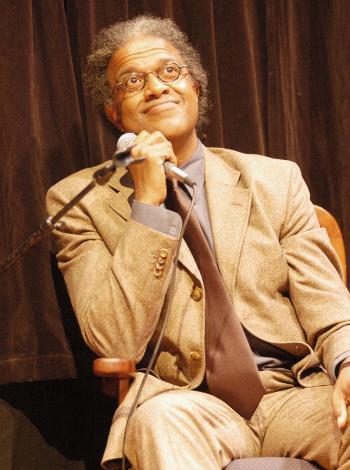

For starters, there’s his well-tended image. He dresses impeccably, and is rarely seen on campus in the same outfit more than once. He frequently wears designer shoes and natty three-piece tweed suits, and his well-tended dreadlocks are one of his trademarks.

“I’m a shopaholic,” Mitchell says when I asked how much he spends on clothes. “If you’re a critic of a visual medium, you should pay attention to how you look.” Still, he acts bewildered—though not entirely unhappy—about all this publicity.

“There are so many rumors about me that I kind of feel like [Tom Sawyer] sometimes, like I’m at my own funeral,” he says.

To use a Mitchell-ian analogy, he attracts gossip like Burberry-patterned flypaper attracts wasps.

Internet blogs have generated plenty of rumors about Mitchell’s personal life. Much of that comes, he conjectures, from the cachet of the Times.

“It’s hunger for whatever it is that the Times confers on people,” he says. “For me, writing for the Times was like being a really ugly person who’d inherited a lot of money.”

Indeed, his unexpected departure from the Times, seemingly one of the sweetest assignments in film journalism, generated a storm of media interest. Other hometown news sources, including The New York Post, The New York Daily News and The New York Observer swiftly attacked the story.

OF SCREED AND TWEED

Searching for some insight into Mitchell’s departure, I called and emailed A.O. Scott ’88 enough times to be sure I was becoming a nuisance. Unfortunately, the Times’ recently minted head film critic never responded.

The busiest speculation about Mitchell over the past year may have been about the circumstances of his departure from the Times. Conjectured causes have included his tendency to unexpectedly take on side projects (like, say, teaching a Harvard class) and friction caused by his many close friendships on the production side of the movie industry.

Despite his mellow demeanor around students, a particularly acidic feature on him last May in New York magazine blamed his Times departure on the fact that his “flamboyant persona has more in common with the movies he writes about than with the paper he works for,” painting him as an opportunistic dilettante with a tendency to abuse his expense account.

However, the direct cause for his departure was widely assumed to be interpersonal friction, which boiled over when his colleague A.O. Scott was promoted to the position of Times head critic. This one, however, turns out to be true, according to the Dredded One himself.

“They said they wanted to make A.O. Scott the lead critic, and that’s not what I signed on for, and I left,” Mitchell says.

Mitchell says that a few other factors contributed to that decision. He describes the Times itself as a powerful institution with some rigid rules, very much deserving of its “Grey Lady” nickname.

“I don’t think you can be [completely] individual at the Times,” Mitchell says. “Using honorifics makes the pieces formal. Times house style demands that you make your voice heard while adhering to this standard.”

Mitchell tells me he volunteered to review the animated Pokemon 2000 just to poke fun at the paper’s insistence on honorific titles.

“I was so excited to write about Mr. Squirtle and Mr. Pikachu, my hands were getting sweaty in the theater,” he says, chuckling, “But they wouldn’t let me…then what can you say about that movie? ‘I think they looked a lot more like the trading cards than I thought they would?’”

Yet another point of contention revolved around his Hollywood friendships and the impartiality demanded by the Times pulpit. Harvey Weinstein, the former Miramax head and one of the most powerful men in Hollywood, notoriously put his arm around Mitchell and said he was his “favorite film critic” after the premiere screening of the 2001 John Cusack romantic comedy Serendipity, according to The New York Observer.

Mitchell went on to pan the film in his review, a twist he says Weinstein found hilarious.

“I’m neither the first nor the last critic to have friends in the industry,” he says, but those friendships were “not enough to compromise my own integrity…I’ve lost friends over it.”

Still, the power of his position forced him to consider the consequences of his often-glib writing, a requirement he describes as an important boon.

“What made a difference was finding little movies and writing about them...sometimes a small independent movie that couldn’t get an ad in the paper would benefit from the added publicity,” he says.

Nevertheless, Mitchell says that the “grueling” Times schedule had started to wear on him, and he does not plan to return to a regular print schedule very soon.

“I felt like I needed a break,” he says. “I’d been doing it for a long time. It’s not always a 9-to-5.”

LIFE AFTER TIMES

After a lecture during Mitchell’s VES class last year, I lingered with my friend Sarah, chatting with the course’s head TF. Mitchell soon drifted by, and we walked through the light spring day to the Red House, next to Brother Jimmy’s.

Over an appetizer of squid cooked in its ink—which proved rather awful—I discussed comics with Elvis. I told him of my affinity for Alan Moore’s seminal series, Watchmen, and he suggested another book: Frank Miller’s Sin City. As it turns out, the latter was a fantastic comic book and made a pretty good movie.

The man’s got an eye for what movie audiences want, and prospective employers have noticed; Mitchell has been busy in the year since his departure from the Times. He’s been named a consultant for Columbia Pictures, a Sony subsidiary, and will soon begin scouting talent and new films in New York for the studio.

Steve Elzer, the VP for media relations at Columbia, was contacted for this article but declined to comment, citing the need to speak to Mitchell first.

Mitchell also says he’s talking to VH1 about doing some “interview and film-type stuff” for them.

Asked if he would become the next Dee Snyder, the former Twisted Sister frontman turned Behind the Music commentator, Mitchell replied, “No.”

Mitchell has also continued his two radio gigs. He has been the entertainment critic for NPR’s Weekend Edition with Scott Simon since the start of the program in 1985, and his nationally-syndicated weekly film talk show, The Treatment, has been running for nearly nine years.

He’s also been omnipresent at film festivals all over the world, “more festivals than I ever knew existed,” he says. For example, he has been named “Guest Curator” for this year’s Los Angeles Film Festival, to be held in June.

Many of these appearances include speeches, such as the one he gave while serving on the board at Sundance, which mocked the types of films that the festival tends to favor. He mentioned several elements characteristic of winning Sundance films: “an acoustic guitar playing mournfully,” “actors from every country trying out Southern accents,” “a generically bittersweet rapprochement,” and “a long scene in a car with a lot of talking.”

Asked to name a prototypical Sundance-type plot, he pointed to the works of Arthur Miller. “[He] could have written Sundance movies,” he says. “Death of a Salesman, if you set it in a trailer park, could have been [one].”

When it comes to his job prospects, Mitchell doesn’t exactly pull a muscle trying to be modest—while at the Times, he tells me, he was offered positions as the editor of Billboard magazine and the head of comedy development for ABC.

“I’ve been incredibly lucky,” he says. “I’ve had more job offers than anyone I know.”

HITTING THE BOOKS

Like many other students during Mitchell’s lectures last year, I would often be cast adrift by a string of cryptic references just to be hooked again with an engaging cinematic argument.

He especially enjoyed using the word “Brechtian,” and I still don’t understand what it means.

Predictably, Mitchell’s aura of controversy, lexical and otherwise, has spread somewhat to his VES class.

Last year’s class was nearly devoid of assigned reading. While there were some suggested books, neither section nor lecture spent much time on the topic of criticism; instead, the films themselves were the focus. I certainly heard some grumblings by the more avid film buffs about the courses “gut-ness.”

In addition, the films on the syllabus were sometimes subject to change. Granted, those changes were often made to accommodate, say, a prerelease showing of Kill Bill, Vol. II or a Bill Murray flick to coincide with the actor’s surprise visit to the class.

This year’s syllabus reflects a more organized approach to the class, with preplanned themes for each week ranging from “The Western and the Mythologizing of Misogyny” to “Food as Sex in Cinema.”

Allan W. Shearer the course’s current head TF, acknowledges that “this is actually the first film class for many people,” but that Mitchell’s unique perspective has the potential to enlighten both newbies and buffs.

“We should always remember that films are made by people, they’re not abstractions delivered in a black box, and Elvis has the experience and ability to make those details clear and evident and interesting,” he says.

For some students, Mitchell’s fast-and-loose lecture style keeps the class exciting.

“I think his lecture style is great, it’s kind of irreverent and fun...I think what he’s trying to say always comes across really easily,” says Ansel S. Witthaus ‘06.

Others, however, needed some practice to decipher Mitchell’s tendency to lace his lectures with esoteric pop-culture terminology.

“For the first couple of lectures I was a little lost with the references but after that I got used to it,” says Inyang M. Akpan ‘07.

Many of Mitchell’s students say he is extremely approachable and eager to discuss film and pop culture. Mitchell is known for making himself available for conversation both after class and during his office hours in the Carpenter Center cafe.

In fact, Akpan says that he saw another student bring a screenplay he had written, and asked Mitchell after class if the critic could read it and give him comments. Mitchell, he says, readily agreed.

Mitchell also appears to be going out of his way to attend undergraduate events. Last month, he moderated the question-and-answer with DJ Spooky, following the artist’s Sanders Theatre performance of “Rebirth of a Nation.”

And a few days later, he attended a Mather House showing of Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle, which Akpan organized. Afterwards, Mitchell led a discussion on the movie’s handling of racial stereotypes.

THE ELVIS STRIKES BACK?

In our recent talk, Mitchell made light of the praise he sometimes receives.

“So, does that moss on your hunchback grow naturally?,” he mimicked with a grin. “Do you need a special shoe for that cloven foot?”

While Gawker and Gadfly have snickered about Mitchell’s class, Mitchell speaks in glowing terms of his Harvard teaching experience. It forced him, he says, to consider the big picture of what he does, to ask himself “what I really cared about.”

If the VES department asks him to, Mitchell says that he would very much like to return, a sentiment that Connor is guardedly optimistic about.

“His position is...allocated to the department to compensate for the loss of the course that might ordinarily be taught by the HFA Curator,” Connor writes in an e-mail. “Since that search is ongoing, I cannot comment on the department’s future plans. I would be delighted to have him back.”

Either way, though, it doesn’t seem like Mitchell will be too upset—should his teaching career be interrupted, he’ll always have those two radio shows, his production consulting job, and a bevy of Hollywood connections to fall back on.

And who needs to worry about when you’ve got the style of a black, male, comic-book-fed Pauline Kael with a penchant for bad ’80s music videos, and a better wardrobe than the love-child of Dorian Grey and Lester Bowie?

---Staff writer Michael A. Mohammed can be reached at mohammed@fas.harvard.edu.

Read more in Arts

Why Do I Keep Super Sizing Me?