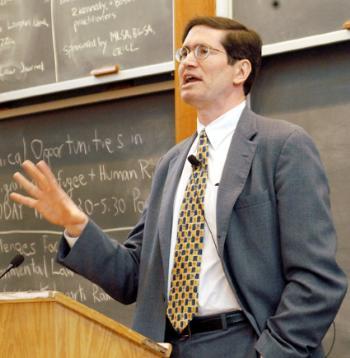

Professor Michael J. Klarman of the University of Virginia School of Law speaks on the first day of Harvard's celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

The Supreme Court that ruled on the historic 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case was “one of the most intensely splintered courts in history,” according to University of Virginia School of Law Professor Michael J. Klarman.

Yesterday evening in a speech titled “Why Brown was a Hard Case,” Klarman described the deep ideological divisions among the justices, who eventually ruled unanimously to end federally sanctioned racial segregation in public schools.

Klarman delivered his talk in Harvard Law School’s (HLS) Austin Hall East to a gathering of about 60 HLS students and professors. The event marked the beginning of the Law School’s week-long commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Brown decision.

Climenko Professor of Law Charles J. Ogletree, who organized the celebration with HLS Dean Elena Kagan, called the Brown ruling the “most important decision by the U.S. Supreme Court on race relations.” He said it was important for Harvard to mark this anniversary in light of the contributions of HLS alums to the case.

As the vice dean of Howard Law School, Charles H. Houston—the first African American to serve on the Harvard Law Review—trained future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and Attorney Oliver Hill, according to Ogletree. Both men played pivotal roles in developing the case against "separate but equal" school facilities. Specifically, Marshall served as chief counsel for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which took the Brown case to the Supreme Court.

Ogletree also said HLS alum William Coleman, who graduated at the top of his class, assisted the petitioner in preparing its case.

At yesterday’s talk, guest speaker Klarman highlighted the “deep, personal animosities” among the justices.

“The only thing that the justices agreed about was that they didn’t have a lot of respect for [Chief Justice Fred M.] Vinson,” Klarman said, referring to the Court’s first hearing of the case in December 1952.

Despite their personal differences, many of the disagreements—the Court was criticized for the myriad of separate opinions its justices wrote on the same case—arose as a result of ideological differences, Klarman said.

When Presidents Franklin D. Rooselvelt, Class of 1904, and Harry S Truman put the justices on the Court, they were “largely indifferent to their racial views,” Klarman said.

For example, Justice Hugo L. Black was a Ku Klux Klan member, although not a very active one, in the 1920s, Klarman said. At that time, the Klan had over 4 million members, and Klarman, speaking as if he were in Black’s position, explained the justice’s rationale for being able to hear the case: “I argue cases in front of Klan members; the only chance I have of winning the case is to be a Klan member. My only chance of getting into politics was to join the Klan.”

Throughout his speech, Klarman quoted from Justice William O. Douglas’ conference notes from the case, which included his observations about the justices and how they appeared to be leaning.

Klarman said several of the justices wanted Congress to “solve the problem” presented in the Brown case. However, “that was just wishful thinking,” he said. “In the 1950s, there was zero chance that Congress would pass a law barring school segregation.”

According to Klarman, the justices struggled with the Brown decision because of the conflict between the “perceived long line of precedent” and their personal values.

Between 1865 and 1935, there were 44 challenges to public school segregation that reached the lower federal courts or high state courts, Klarman said. All were unanimously rejected. In 1896, the nation's highest court decided in Plessy v. Ferguson that “separate but equal facilities,” including public schools, were constitutional.

Read more in News

Mahan Unveils New Harvard-Yale Game Plan