With Harvard’s largest curricular review in 25 years and its largest physical expansion in history underway, the University is preparing to set another record—the most ambitious capital campaign in the history of higher education.

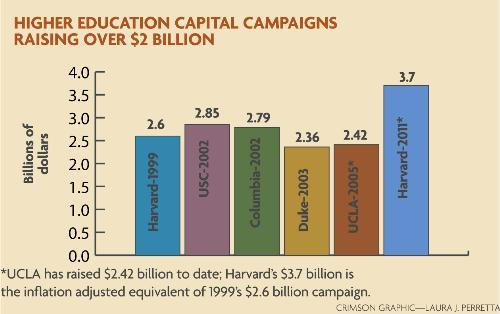

Officials running the fundraising drive, which is slated to officially begin later this year, say it will outpace Harvard’s last University-wide campaign, which finished at $2.6 billion and at the time was nearly $1 billion larger than any other completed higher education campaign.

The campaign will try to attract donors to fund some of University President Lawrence H. Summers’ oft-repeated goals, which include revamping undergraduate education, creating ambitious new science programs, developing the University’s campus of the future in Allston and supporting public service careers.

Summers himself just returned from a two-day development trip in New York City, where he said he floated early plans for the campaign with potential donors.

Vice President for Alumni Affairs and Development Donella Rapier said that in contrast to the last campaign, which placed more focus on the goals of individual schools, Summers plans to emphasize University-wide and cross-faculty initiatives in his fundraising efforts.

None of the specific details of the campaign have been officially hammered out, Rapier says.

“The total dollar goal is not decided, the time is not decided,” she says. “So we’re really in the very, very early planning stages.”

But she says that Harvard has committed to beating 1999’s $2.6 billion figure by more than inflation. This means that—based on a higher-education inflation rate of 3 percent and adjusted for inflation through the end of the campaign’s potential seven-year length—the goal will be to take in at least $3.7 billion, or $850 million more than the largest currently finished campaign, conducted by the University of Southern California and completed in 2002.

Development officials and senior administrators are beginning to discuss the campaign with major donors. Rapier outlined campaign plans to the approximately 90 alumni directors at a meeting last month, according to Harvard Alumni Association Director Jack Reardon.

“We’re spending a lot of time and energy now on thinking about exactly what we would do and how we would do it,” Rapier says.

Summers described the University’s current activity as comprising the “pre-quiet phase” of the campaign.

This campaign will begin five years after the close of the previous campaign, which ran from 1992 to 1999. Administrators and faculty said at the time of former President Neil L. Rudenstine’s retirement that his prodigious fundraising efforts would relieve his successor of the need to lead another campaign in the near future.

But Summers began mulling a campaign just a year into his tenure. Now, only two years after Rudenstine’s departure, he committed to a major campaign, a testament to the fact that the billions required to fund major science projects or move entire graduate schools to Allston will far exceed Harvard’s current resources.

Rapier, who was promoted this fall from her position as chief financial officer at Harvard Business School (HBS), was hired largely with a mandate to oversee the coming campaign, she says.

“A large part of what I’ve been hired to do is figure this out,” she says.

And while the University can count on one of the world’s richest pools of alumni to support its efforts, many obstacles remain.

The University-wide campaign might overlap with—or even overshadow—ongoing campaigns at the Harvard Law School (HLS) and HBS. Rapier says those campaigns, with goals of $400 and $500 million, respectively, might be folded into the larger University campaign.

Rapier says a decision has not been made on whether to conduct a targeted campaign centering on a few major goals like science or Allston or whether to pursue a broader, more general campaign instead. While a general campaign would include individual schools’ goals to a greater extent, Harvard and outside fundraisers say its easier to interest the richest donors in initiatives or buildings that figure into Harvard’s long-term priorities.

And a mere five years after the last campaign, donor burnout is a problem Harvard must strive to avoid.

THE SHOPPING LIST

Rapier says the plan for a multibillion-dollar fundraising drive has been fueled in large part by Summers’ desire to push cross-school objectives like financial aid for graduate students going into public service as well as the bigger priorities like Allston—which will likely move science facilities, two entire graduate schools and undergraduate Houses across the Charles River.

“This is a component of his objective of really trying to be greater than the sum of the parts,” Rapier says. “In order to really interest donors at the very, very high end, they want to participate in something that’s really University-wide as opposed to in discrete chunks.”

Rapier says the curricular review is frequently discussed with alumni and will play a crucial role in shaping the goals of the campaign.

“A lot of [the campaign] is being driven by the curricular review,” she said, identifying financial aid, study abroad, increasing the size of the faculty, and more science education as key talking points for donors.

While the College has begun to loosen the requirements for term-time study abroad, it still lacks the extensive programs featured by its peer universities.

The expansion of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences—a planned increase of 60 faculty over 10 years—will benefit from the fundraising as well.

Expanding cutting-edge science research, another Summers favorite, will also be highlighted as a major objective of the campaign.

“The things that are happening in the science world are going so fast...and they are very, very expensive,” Rapier says. “There’s definitely a tremendous amount of needs in terms of the research and lab spaces and physical spaces and faculty.”

To date, Harvard has already committed to a number of costly and ambitious science initiatives.

The Broad Institute, a joint genomic venture with the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research and MIT, will cost the University at least $100 million. The University is planning a stem cell center that The Boston Globe reported will cost another $100 million.

And the University had already committed money to a spate of smaller initiatives, with more on the way.

An increased commitment to public service would also be a focus of the campaign. Summers has created a three-year, $15 million graduate student financial aid program to support graduate studies in low-income fields.

The lynchpin of the campaign will likely be the University’s new campus in Allston. The planning and construction of the campus across the river—where Harvard owns more land than it does in Cambridge—will cost billions of dollars, as the center of the University is moved from the John Harvard statue to the Charles River.

Summers’ current plan for the new campus would create a science nexus, including many of his major initiatives, move the Graduate School of Education and the School of Public Health and add housing—graduate housing and possibly new or relocated undergraduate Houses.

Hundreds of millions of dollars have already been spent to acquire and begin clearing land across the river, and billions more will likely be required to prepare the land and begin construction of the first parts of the new campus, which could happen as soon as five years from now.

So far, most of the Allston expenses have been covered by a five-year tax levied on the schools’ endowments. That tax was just extended to 25 years to defray future costs.

But as expenses begin to soar with groundbreaking on the horizon, more money will be needed to fund the University’s expansion.

PLANNING THE CAMPAIGN

Rapier says the administration has been considering a campaign for the last year, when the idea was first raised with senior development and central administration officials.

But she adds that these administrators feel more ready to launch a campaign now that academic and physical planning across the University is further advanced. Committees on both Allston and the curricular review will release preliminary conclusions this spring, and the University is narrowing the search for a firm to plan its Allston campus.

Allston is figuring prominently into the still unresolved question of the length of this campaign.

Campaigns tend to be seven years, although the University is considering a 10-year campaign that would extend further into Allston construction and thus more substantially offset Allston costs. The other option, Rapier says, is to hold a seven-year campaign now and another one as Allston work progresses.

Although the effects of the recent recession on giving have weighed on the minds of development officers, the economy does not generally have a major impact on education donations, according to John Taylor, vice president for research and data services at the Council for Advancement and Support of Education, a Washington-based advocacy group that tracks higher education fundraising.

“Education in general and higher education in specific seems to be very resilient when it comes to fundraising campaigns,” Taylor says. “The economy doesn’t seem to have a substantial dampening effect.”

With the economy now on an upswing, the time is ripe to kickoff a campaign, he says.

“If they are planning on going into a campaign in the next year, the conditions couldn’t be better,” he says.

Andrew Tiedemann, a spokesperson for the University Development Office, points out that it has been 12 years since the last campaign started and thus since Harvard development officials last tried to solicit so-called “nucleus fund” donors.

“That’s a long time for an institution of this size,” he says. “This is the first major review of Harvard’s planning and mission in 12 years.”

Reardon says that while there is concern about donor fatigue, the University needs to continue raising money to support its ambitious goals.

“That’s always a question,” he says. “One of the problems is that there are a lot of things that you want to do—you have huge needs...so that’s kind of an ongoing situation: the place has a lot of money but it always needs a lot of money.”

Taylor says it’s not unusual today to leave little time between successive campaigns, noting that the most likely kind of burnout is if donors are no longer interested in the priorities emphasized in the last campaign, preferring instead to spend their money on new initiatives.

“Institutions are almost constantly in a campaign,” he says. “As soon as you finish one, you start to gear up for the next one.”

And Council for Advancement and Support of Education Director of Public Relations Joye Mercer Barksdale says the major donors are used to being solicited repeatedly.

“The very sophisticated donors that Harvard is dealing with—they know enough about the challenges higher education is dealing with to know that Harvard will need to come back to them over time,” she says. “So I don’t think it’s a one-shot deal.”

Taylor says that the outcome of the internal debate over the merits of a smaller, targeted campaign versus a broader cross-school campaign is unlikely to have major ramifications on its financial success.

“The only real difference between the two is that one counts everything including the kitchen sink and the other only counts gifts that are made towards those three or four featured priorities,” Taylor says. “There’s no real negative either way.”

“The only positive of going with the larger campaign is that you could announce a larger goal, because you are including everything,” he adds. “The positive of going with just the focused campaign is that you can market that much more aggressively.”

—Staff writer Stephen M. Marks can be reached at marks@fas.harvard.edu.

Read more in News

Chapel May Remain in Cambridge Permanently