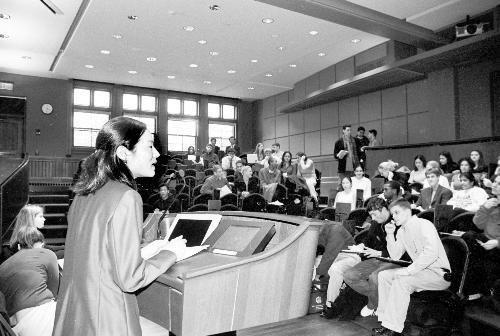

Undergraduate Council President SUJEAN S. LEE ’03 leads a meeting in Sever Hall, where the council holds its weekly meetings. The leaders of the council are elected by the entire student body.

Every one of Harvard College’s 200 extracurricular activities has a leader.

Extracurriculars provide opportunities for students to pursue their ambitions and reach the tops of organizational ladders. But these ascents take many different forms precisely because the hierarchies being climbed are so varied.

Even the hundreds of organizations that receive funds from the College’s Undergraduate Council and are subject to the College’s oversight have few formal restrictions upon who may vie for leadership posts.

According to the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Student Handbook, “All officers and a majority of the members” of an organization “must be registered undergraduates.” Organizations’ heads must also keep track of finances, and those students on academic probation “must attend all classes and be especially conscientious about all academic responsibilities.”

Aside from these regulations and the prohibition of discrimination “on the basis of race, creed, color, sex, sexual orientation, or physical disability,” College-funded organizations enjoy almost complete autonomy in their selection processes.

With so much leeway, procedures for choosing leaders vary widely among these organizations—ranging from the purely democratic to the exclusive.

And College groups that are financially independent from Harvard add even more variability to the mix.

The campus-wide voting for the president and vice president of the Undergraduate Council sharply contrasts with the cryptic rituals of the Harvard Lampoon, a semi-secret Sorrento Square social organization which used to occasionally publish a so-called humor magazine.

But the gamut of selection processes for the heads of extracurricular groups ultimately serves as an indicator of a group’s perceived internal harmony. The more democratic a group’s election procedures are, the more likely it is for its controversies to become public knowledge.

Democracy’s Discontent

Winston Churchill once noted that “democracy is the worst form of government, except all those other forms that have been tried from time-to-time.”

At Harvard, organizations with democratically elected leadership have had their fair share of travails in recent years.

The Undergraduate Council, the Harvard College Democrats and the Harvard Republican Club (HRC)—all political organizations that choose their leaders through democratic voting systems—have each suffered from recent electoral controversies.

In early 2000, council Vice President John A. Burton ’01 was impeached for his alleged theft of over 100 pin-on buttons from the Bisexual, Gay, Lesbian, Transgender and Supporters’ Alliance office for use in his campaign with his running mate, council President Fentrice D. Driskell ’01.

Although Burton survived the impeachment, the imbroglio severely weakened Driskell’s administration.

Problems emerged again in November 2001, when Anne M. Fernandez ’03, who was the council treasurer at the time and who had been planning a presidential bid with then-council Finance Committee Chair Trisha S. Dasgupta ’03, decided instead to run for vice president alongside then-council Vice President Sujean S. Lee ’03.

The Lee-Fernandez ticket won, despite Dasgupta’s claim that Fernandez reneged on a formal agreement.

According to the constitution and bylaws of the council, a popular vote by the College student body determines the president and vice president.

The council is not the only organization with recent democratic electoral problems.

Two months into the last academic year, the College Dems were divided when an e-mail was sent out encouraging non-Democrats to join the club for the sole purpose of voting for Geoffrey F. Reed ’03, a candidate for the club’s presidency.

John F. Bash ’03, Reed’s friend, sent two e-mails plugging Reed’s candidacy, including one that asked recipients to join the College Dems, regardless of political affiliation.

Reed sent out an e-mail of apology soon after Bash’s e-mails, disavowing any responsibility for them and stating that he does not support non-Democrats joining for electoral reasons.

Sonia H. Kastner ’03, who ran against Reed and condemned the e-mails, ultimately won the presidential race.

All members of the College Dems are permitted to vote for the president.

This procedure of direct election, while it may enhance the representation it provides for members, might also lend itself to electoral problems.

Kastner says that the democratic election of the council’s president and vice president may occasionally give rise to problems, but that such difficulties are worth the price.

“A lot of times, these election scandals get blown out of proportion,” she says. “For all the positions, really good people were elected.”

Scandal also struck HRC elections two years ago.

Robert R. Porter ’00-’02 and Erin L. Sheley ’02, who were running for the club’s presidency and vice presidency, respectively, had urged non-Republicans to join the organization for the purpose of voting in the election. Other candidates employed similar tactics, according to club members.

“Nobody broke the rules,” says current HRC President Brian C. Grech ’03. “They kind of pushed the line of how far you can go to run for president.”

Membership in the club shot up from 75 to 101 in the week preceding the election.

Porter, who denied wrongdoing, was elected, while Sheley, who later expressed regret for her tactics, lost her bid for vice president.

With the high incidence of controversy in recent years among groups who choose their leaders through democratic elections, some feel that the democratic process might lend itself to some difficulties.

Assistant Professor of Law Heather Gerken, who teaches a course on democratic theory and election law, cites two theories.

“Transparency is certainly the most obvious explanatory factor,” Gerken says, noting that open elections will reveal scandals more readily than in selections that take place behind closed doors.

Gerken also observes that the causality may be reversed.

“Large organizations have a tendency not to have as much trust among members,” she says. “The smaller the group, the stronger the bonds.”

As a result, she says, it is uncertain whether democratic selection processes are best for all organizations.

“It’s a hard question. There are all sorts of trade-offs here,” Gerken says. “Does everybody feel like they had a voice? That’s important.”

Middle Ground

The majority of campus organizations resort to consensus-based systems, which are not direct democracies but which allow certain group members to help determine their organizations’ future leadership.

The Harvard University Band’s student leadership body—the senior staff—is chosen by each successive senior staff.

According to Chris A. Lamie ’04, the band’s student conductor and member of the senior staff, the selection process entails an application and audition process.

“We don’t want to turn people away,” Lamie says. “People who apply want to make a contribution.”

Those who do apply then audition for the positions.

“I can’t really elucidate much on that,” Lamie says, referring to the auditions. “There are some things even people within the band don’t know.”

After the auditions, the senior staff then makes its decisions, although the selections don’t take place in a vacuum.

“While it’s not an election, we certainly seek input from the rest of the band,” he says.

A wide variety of organizations—from the fraternity Delta Upsilon to The Crimson—employ consensus-based systems of different sorts.

Lamie says such procedures afford current leadership a measure of flexibility in choosing its successors. They also provide some guarantee that future leadership meets certain criteria, meritocratic or otherwise.

Behind Closed Doors

And then there are those groups that don’t even come close to the middle ground.

In contrast to organizations that choose their leadership through open elections, there are also those that guard their rituals and processes jealously.

A prime example is the Lampoon, whose leadership selection procedures are insulated from the outside world. In fact, most of the titles borne by members of the Lampoon’s board of directors are inscrutable to the uninitiated.

Sean D. Boyland ’01-’03—the group’s “ibis,” or its second in command—explains facetiously that the organization’s selection process is meritocratic.

“It’s a series of fights,” Boyland says. “Sometimes there are small weapons involved.”

“We’re mainly interested in how well people fight,” he continues in jest. “That’s the merit we’re concerned about...Funny guys fight well. And funny ladies.”

Perhaps due to the secrecy that shrouds the Lampoon’s electoral process, few controversies over its leadership decisions have ever become public.

Yet freedom from public scandal is not enough to reassure some first-years that their aspirations are best invested in the Lampoon or similarly secretive organizations.

“The danger is you’re going to get small cliques running the whole thing,” Neil P. Herriot ’06 says.

—Staff writer Alexander J. Blenkinsopp can be reached at blenkins@fas.harvard.edu.

This is the second article in a series examining student groups at Harvard. Tomorrow: Two years after turmoil, where does the IOP go from here?

Read more in News

Top Israeli Official Talks Policy