Club Passim, where Joan Baez and Bob Dylan got their start, still holds folk concerts nightly after 45 years as one of the Square's quintessential cultural institutions.

Harvard Square often bustles with street performers, musicians and eccentric artists looking to entertain. But the Square also supports a well-respected music and nightlife scene that often goes unnoticed by Harvard students, who tend to reserve Friday and Saturday nights for the Loeb, the Fly or the fallback beer-filled dorm room.

But two history-rich Harvard Square establishments have provided their own unique entertainment for years, becoming mainstays in the area for a night out any day of the week.

HOUSE OF BLUES

The founder of the House of Blues, “a gentleman by the name of Isaac Tigrett, who had a passion for the blues,” is better known for having started the Hard Rock Café chain, with which he is no longer involved, according to marketing and publicity manager Lisa M. Bellamore.

A native of Jackson, Tenn., “his life goal was to introduce the world to blues as well as to southern culture,” Bellamore said.

Together with his friends, the actors Dan Akroyd and the late John Belushi, he opened up the House of Blues in Harvard Square. Ten years later, eight more clubs have opened up across America.

During the day, House of Blues is a “soul food” restaurant decorated by funky portraits of blues legends. At night, it offers up rock, reggae, funk, world and, of course, blues concerts for every night of the week, in addition to programs such as the summertime Blues Cruises—a chartered boat providing concerts every Friday at Boston Harbor—and the Gospel Brunch every Sunday.

With so many different kinds of music offered, Bellamore says House of Blues does not attract a specific type of person to its gigs, but that the “band dictates the crowd.”

At a concert of the funk band Milo Z on a recent Saturday, the crowd consisted of mostly 30-somethings, out to bump into each other and have a good time.

The venue, which has a small stage up front and a long bar at the back, is just small enough so that the atmosphere seems intimate.

During the intermission and after the show, members of the band mingled with the audience, to the delight of those schmoozed. The lead singer also walked down into the audience frequently, and later brought a dozen or so audience members up to dance on the stage with him for the final number.

The same interactive spirit prevailed at the Sunday Brunch, whose audience was much more touristy—two-thirds of it had been imported from the Bronx on a bus tour for the elderly.

The emcee came on stage from the back, playing “Oh, When the Saints” on the trombone, and giving many in the audience a brassy earful.

From that point on, the audience was made to holler out boisterous “Hallelujahs” with considerable frequency throughout the show, as well as having to sing the occasional chorus and, for one song, wave its arms in what it was told was the “love” hand position in sign language.

Eager sightseers and slow-moving octogenarians alike seemed to get into the spirit—at least after the emcee shouted long enough at them to get into the mood.

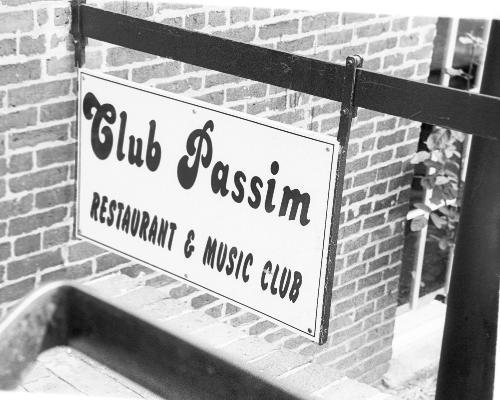

CLUB PASSIM

Club Passim has been a fixture of Harvard Square since the 1960s, when it used to host folk musicians like “Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Bonny Raitt and everyone else you can think of,” according to music operations manager Matthew H. Smith.

Founded as Club 47 in 1958 in a 125-capacity basement on Palmer Street, between Eliot and Church Streets, it was immensely important in fueling the ‘60’s folk movement. Joan Baez and Bob Dylan played their first public gigs ever at the Harvard Square joint.

In 1969, new owners, Bob and Rae Anne Donlin tried to convert the space, which had been run on a non-profit educational charter, into a bookstore called Passim. But the demand for folk music never died down, and they soon found themselves “forced into booking music again,” according to Smith. The Donlins were soon doing so well, they at one point turned Bruce Springsteen down for a gig.

Club Passim has been open in its latest guise since 1994 as a folk and acoustic music haven. Like House of Blues, it has concerts every night, as well as a Sunday brunch show. But at Club Passim, all the shows are meant to be enjoyed over a non-alcoholic vegetarian or vegan meal.

The Club’s special feature is its Tuesday open mike sessions, to which regularly featured artists and green high schoolers alike regularly sign up, according to Smith. Names can be put down beginning at 6:30 p.m., and the order is then drawn at random at 7 p.m.

Smith said the open mikes are extremely popular—one night, 83 people out of a maximum seating capacity of 125 signed up to sing.

One of those who signed up a few weeks ago was that week’s Wednesday night headliner, folk singer Christopher Williams, who said he used to go to open mikes before his career started taking off.

“One of the coolest things about the club is that they support people’s careers really early on,” said Williams, who used to volunteer ushering at the club before they gave him his first smaller concerts.

Wiliams says he is giving a part of the proceeds from his last album, Side Streets, to Club Passim in recognition of the influence it has had on his career.

During his sold-out concert, it was apparent that the virtuosic guitar, African drum and harmonica player had a very chummy relationship with the club, when the manager kept shouting out to him periodically throughout the show.

“You two look so good together, should we leave the room?” he yelled at one point when Williams chit-chatted briefly with a girl in the audience.

And the venue has a low-key feel by the nature of its set-up, with a window right on street level through which passers-by often crouch down to look in on the concert. At one point in his gig, Williams invited in some people he knew who had held up signs in the window cheering him on.

“There are definitely a lot of regulars,” Smith said. “It’s got that everybody-knows-your-name atmosphere.”

—Staff writer Eugenia B. Schraa can be reached at schraa@fas.harvard.edu.

Read more in News

Clarke Blasts Bush’s Policy on Terrorism