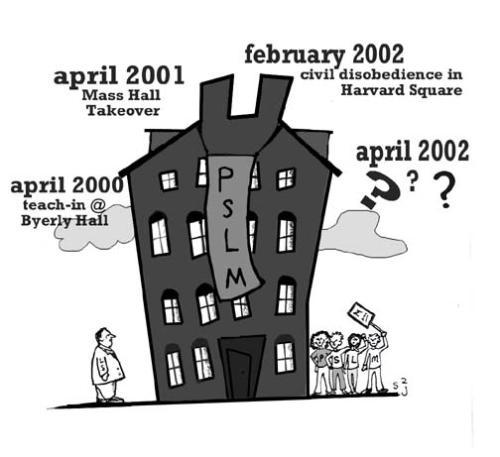

Do you remember when you were learning to swim? Did your parents place you in the water and then tell you to swim towards them, but slowly walked backwards? Members of the Progressive Student Labor Movement (PSLM) must remember this experience well, because they are using just such a tactic in justifying their increasingly extremist cause. They should collect their chips now to preserve their waning credibility.

The result of the University’s negotiations with the janitor’s union surpassed the expectations those of us who prepared the Harvard Committee on Employment and Contracting Policies (HCECP) report. The HCECP thought a wage in the range of $10.83 to $11.30 per hour would be an appropriate outcome. The janitors got $11.35. The HCECP exceeded its mandate and recommended more access to health care for low wage employees. The University gave substance to the HCECP’s intentionally vague recommendations concerning health care by vastly increasing access to health benefits. The single most important recommendation, the parity policy to ensure that outsourcing will never again occur at the expense of workers, was implemented.

Anyone claiming the University somehow failed to live up to the report in these negotiations is not telling the truth. In fact the only thing that did not live up to the cooperative spirit of the HCECP was the public nature of the negotiations, which served as an encouragement to gamesmanship, not bargaining.

So what is the future of the living wage campaign on campus? Let’s first take our activist friends at their word. Apparently, PSLM had not done enough research before taking over Mass. Hall last spring and have now determined the Cambridge living wage isn’t enough. According to PSLM member Madeleine S. Elfenbein ’04, “The Cambridge living wage is not a scientifically determined minimum that will suffice in this area.” I tried calling my local “living wage scientist” to ask the same question, but he never returned my call. Casting about for any “scientifically determined minimum” I found a strange concept known as the “poverty line.” Excited by this discovery I hurried to report it to the living wage campaign. My excitement was dampened, however, when I discovered that the poverty line would yield an hourly wage of $9.05 for a family of four. I didn’t quite know how to break it to Elfenbein that under her theory, the janitors should accept an immediate $2.30 an hour wage cut. Although such a statement is outrageous, so is the notion that a wage level can be scientifically determined. The federal poverty line is an inappropriate measure for the Boston area and is an inexact number itself. The very idea that one can “scientifically determine” some wage that will prevent poverty is ridiculous.

The inability to “scientifically determine” an appropriate wage number is partly a result of having families with different numbers of children and wage-earners. PSLM never discusses whether Harvard should have to pay a worker with more children more money or why Harvard should have to factor this into their wage scales. Of course, leafing through PSLM literature I found their own research yields the scientifically precise living wage figure of $11 to $22 per hour. These numbers leave a wonderfully wide area in which to advocate for ever higher wages. Are janitors being offered only $15 an hour? Quick to the crosswalks!

The pressure tactics PSLM used were instrumental in winning concessions at the negotiating table. No doubt the ratio of 5 students to 3 labor organizers to 1 janitor arrested in their choreographed mock civil disobedience struck fear into the university.

No doubt our activist friends will brush off the tired argument that a few colleges like MIT or Wellesley pay over $14 per hour, so why not Harvard? Harvard has the most money, so Harvard should pay the most. But PSLM sees the world with tunnel vision. They always leave out that in comparisons to other Boston area schools, Harvard is in the middle of the pack, not the bottom as they pretend.

Otherwise, their “piggy bank theory” of the Harvard endowment is still wrong. Money that goes to the janitors cannot go to other University operations, including those more vital to its academic mission. Wage increases mean either fewer resources devoted to other programs or a need for increased revenue, higher fees or tuition. Collective bargaining is the appropriate mechanism for arriving at a contract, not limits pre-determined by excited students. Apparently, collective bargaining worked this time since the university expressed satisfaction and the janitors’ union ratified it by a 270-8 vote. But PSLM member Matthew R. Skomarovsky ’03 insists, “It could be said that whereas workers accepted the wages in the sense they agreed to the contract, by no means did workers think that those wages were fair or adequate.” It could also be said that whereas janitors know what’s in their own best interests and were perfectly capable of continuing negotiations since their old contract had months still to be completed, by no means should students like Skomarovsky pretend to know what’s in the workers best interests.

Last spring PSLM exposed some shameful University bargaining practices. The campus community owes them thanks for that. The problems were fixed. Last spring it was possible to admire PSLM for their dedication to what they saw as a moral cause: the single policy option of the Cambridge living wage. Now Elfenbein says, “I think it was a mistake for students to fight for the Cambridge living wage as a moral standard for Harvard.” Can PSLM ever be taken seriously again?

In the aftermath of their opportunistic abandonment of this policy it is impossible to view them as anything but an ideological advocacy group with no concrete principle beyond the idea that workers deserve more. It is this collapse of principle more than anything else that has led to general student satisfaction that Harvard’s own Willy Wonka, University President Lawrence H. Summers, will greet any future self-indulgent cries of “Daddy, I want an oompah-loompah now!” with the swift revocation of the golden ticket to the Harvard candy factory.

In his farewell address Douglas Macarthur said that “Old soldiers don’t die, they just fade away.” I wish the same could be said for student labor groups that have lost their purpose.

Matthew Milikowsky ’02 is a history concentrator in Mather House. He was a member of the Harvard Committee on Employment and Contracting Policies.

Read more in Opinion

Remembering September 11th