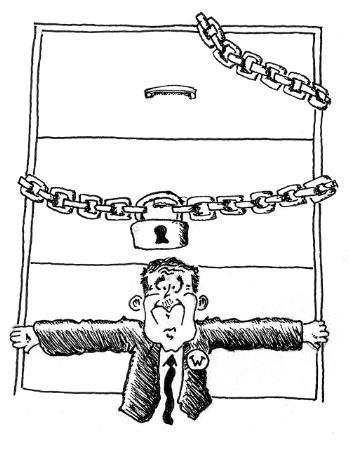

Once again, President George W. Bush and his administration have demonstrated an unsettling disdain for transparency in government. Thousands of documents from Bush’s tenure as Governor of Texas are locked up at George H. W. Bush’s presidential library, out of the public’s reach.

Even though Texas state law requires that all requests for state records be answered within 10 days, the federally-funded presidential library does not have the manpower to even catalog the 1,800 boxes of gubernatorial records—let alone to respond to file requests—in such a brief period of time. Much to the dismay of Texas’ state archivist, who has the resources to handle the thousands of pages and has been one of the most vocal opponents of Bush’s scheme, the shortest notice the library can give petitioners is 90 days. And because it is a federal institution, it claims no allegiance to Texas state law. As James Newcomb of the Better Government Association summed up, “Who needs a shredder when you have Daddy’s presidential library?”

Controversy over the fate of the records came to a head as news organizations and public interest groups asked for documents relating to the president’s relationship with the Houston-based Enron Corporation. The failed utilities trading firm was suspected of donation-bought political influence, especially in its home state. It is certainly reasonable that Bush’s public records be easily accessible to the public, especially to aid the investigation of Enron’s collapse and the terrible blow it dealt its employees. The current situation hardly promotes the transparency necessary for our democratic institutions to prosper, and it most certainly hinders this vital inquiry.

This is not the only time Bush and his cohorts have had trouble releasing documents. The General Accounting Office (the investigative arm of Congress) is currently suing Vice President Dick Cheney over records of his consultation with top Enron officials in crafting the administration’s energy policy.

While Cheney maintains that the privacy of those documents must be protected to ensure that the administration receives “unvarnished advice” from energy execs, their self-interest in energy policy gives that advice an unacceptable varnish from the start. Bush’s evasiveness only makes it seem as if he has something to hide.

Bush cannot even let go of documents from the Reagan years. In an executive order, he prevented the release of thousands of records slated for release months ago, even though existing bureaucratic checks would protect sensitive information from inclusion. It is hard not to point out that the Bush administration is filled with former Reaganites and that Bush’s father has obvious connections to those regrettable eight years. It is impossible not to question Bush’s motives in these cases.

Bush and his subordinates should make government records easily accessible to the public. Fighting for democracy around the world is incompatible with sabotaging the proper functioning of honest government at home. Governmental accountability is the central principle in American democracy, and as it is such an essential principle, it should be willingly and gladly upheld—especially by those in the upper echelons of power. The current administration should avoid even the appearance of impropriety rather than leave the American people to guess at some documents’ possibly damning contents.