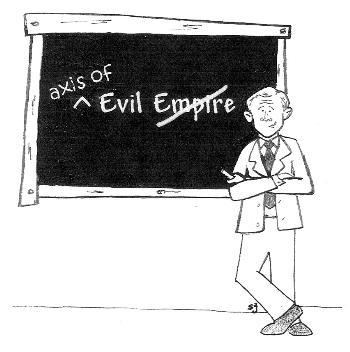

President George W. Bush’s State of the Union address is already being dubbed the “axis of evil” speech, much as former President Ronald Reagan’s address to the National Association of Evangelicals on March 8, 1983, became known as the “evil empire” speech.

Reagan cautioned against ignoring “the aggressive impulses” of the totalitarian Soviet regime, which he called an “evil empire.” Bush singled out Iraq, Iran and North Korea as examples of repressive states that “constitute an axis of evil, arming to threaten the peace of the world.”

And just as Reagan was initially derided for his strong words back in 1983, Bush is also being chastised for his stern language. The Crimson called it “irresponsible rhetoric,” while the Washington Post’s Helen Thomas labeled the address a “bellicose speech” delivered by a recklessly “belligerent American president.”

How quickly we have forgotten Reagan’s legacy.

It’s no secret that many politicians idolize Ronald Reagan and all of his achievements. Since the Gipper left office in 1989, countless Republican and more than a few Democratic candidates have tried to present their platforms as being inherently “Reaganesque.”

Yet, few have been able to capture his style of straight-talk on foreign policy matters. When it comes to this quality, most public officials have failed the “Reagan test” miserably.

Reagan was unafraid to apply moral pressure on those nations that were stifling individual freedom, developing dangerous weapons and actively seeking to undermine democratic institutions. Consequently, when advisors and cabinet members urged him to eliminate the phrase “evil empire” from his now-famous speech, Reagan insisted that it remain.

Natan Sharansky certainly appreciated those two famous words. He was a prominent Russian scientist and human-rights activist who was arrested in 1977 during a typical Soviet crackdown on “dissidents.” Imprisoned in a gulag labor camp, his heart swelled when he heard the news of Reagan’s address. In Peggy Noonan’s new book “When Character Was King,” Sharansky remembers, “There was fear in the West to deal with the Soviet Union,” but “Reagan was one who understood the Soviet Union is [an] evil empire and we could change it.” Pressure from the U.S. government led to Sharansky’s release, and when the Soviet dissenter was subsequently invited to the White House, he had high praise for America’s leader: “I told him that his speech about the “evil empire” was a great encourager. An American leader was calling a spade a spade—he understood the nature of the Soviet Union.”

Reagan’s speech shattered the illusions of moral relativists everywhere and highly embarrassed the Soviet government. It indicated that America would no longer make excuses for brutally despotic regimes that threatened our national security. As Noonan writes, “dictatorships cannot continue forever in an atmosphere of truth…[Reagan] refused to lie, and with his words the fall of the ugliest dictatorship in human history began.”

Both in language and action, Reagan would not remain complacent in the face of tangible danger; passive co-existence with a tyrannical enemy wasn’t an acceptable option.

Following in the former president’s path, Bush has promised that he “will not wait on events, while dangers gather” and “will not stand by, as peril draws closer and closer.” We will not allow “the world’s most dangerous regimes to threaten us with the world’s most destructive weapons.”

The new “axis of evil” countries were obviously displeased with Bush’s speech, just as the Soviets were upset with Reagan’s. They are disturbed that an American president might take the initiative to free their people from vicious totalitarianism and restore their God-given human dignity.

Bush has presented an honest depiction of aggression and atrocities in these “axis” nations, and the truth is staggering.

North Korea lets its citizens starve while it devotes nearly one-fifth of its economy to military expenditures. Pyongyang officials also aggressively pursue nuclear weapons, and they shocked the world in August 1998 by firing a test missile over Japan.

The Iranian regime violently suppresses democratic movements among its country’s youth, and works to develop advanced nuclear capabilities—using North Korean technology, in many cases—for its warheads.

The list of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein’s misdeeds is overwhelming. Besides shunning international weapons inspectors, seeking to obtain nuclear missiles, torturing political prisoners and starving his own people, Hussein “has already used poison gas to murder thousands” of native Iraqis, as Bush noted.

By acknowledging the inherent evil and potential danger of these three rogue states, Bush gave them a clear and uncompromising message: America is watching you, and after Sept. 11 we will no longer tolerate your nefarious actions.

Apparently, the message has been received in Pyongyang. James Hoare—Britain’s top North Korean envoy—claims that North Korea is now especially concerned “that the doctrine applied to Afghanistan could be applied to other countries,” and they wish to reopen discourse with the United States. In other words, they fully realize the seriousness of the Bush administration—a “seriousness” that could adversely affect them if they don’t move quickly.

The president’s moral clarity is refreshing and more than a little “Reaganesque.” Bush realizes that making demands of these malevolent regimes is not—to borrow a Reagan phrase—“cultural imperialism,” but rather an honest attempt to affect progressive change and protect the political institutions, infrastructure and people of the free world.

His “axis of evil” speech will surely go down as a landmark event in the history of American diplomacy. He has inaugurated a new climate of honesty and reinvigorated the potential of our foreign policy.

And by doing so, Bush has passed the “Reagan test” with flying colors.

Duncan M. Currie ’04, a Crimson editor, is a history concentrator in Leverett House.

Read more in Opinion

Remembering September 11th