In the middle of the day only a few businesspeople, construction workers and local shopkeepers sit on the brick benches surrounding the Harvard Square MBTA Station. But around 3 or 4 p.m. the kids start to congregate, talking, greeting one another with hugs or just sitting and watching the passers-by. Most of them are local kids who come here after school, but about 20 of the 100 or so regulars are homeless, often migrants drawn to Harvard Square from around the country, but almost indiscernable from their high school friends. With their mohawks, piercings, brightly colored hair, leather and studs, the pit kids are hard to miss. But Harvard students routinely walk right by them as if all that attention-getting eyeliner were so much invisible ink.

Or at least they did until two weeks ago.

Then, in one fell swoop 150 Harvard students and affiliates descended silently into the pit kids' domain--their community center if you will--in order to express their moral outrage at an assault on a Harvard student that was being investigated as a hate crime. The terrible spectre of an invasion of skinheads onto campus loomed out of the dark recesses of Harvard's collective imagination. The kids with the tattooes, with the shaved heads or green hair--they were the target of the protest, they were the skinheads. Or so Harvard to all outward appearances agreed.

But there are serious questions about whether this crime--one of three assaults in September termed as hate crimes--was actually committed by skinheads. "What if?" is the title of an anonymous xerox that was being handed out in the Square last week. It tells the disjointed tale of an undergraduate caught in the middle of a fight between a rude Harvardian and a couple of homeless kids.

This is also the story the assailant is telling the press from his cell in the Middlesex County Jail in Cambridge. And listening to the people who know the Square best, his story jibes well with other kids' experiences with obnoxious Harvard students.

Michael Sullivan, who first came to Harvard Square in 1969, has spent the last 11 years working at the Bread and Jams day-time drop-in shelter in the Old Baptist Church. He describes a peaceful coexistence between pitsters and students--except for those times when Harvard students, drunk and stumbling home from a party or a bar, make the off-hand derogatory statement, or perhaps are out-and-out rude. These clashes occur about four or five times a year, according to Sullivan, usually at the beginning of the semester when Harvard students are most likely to be partying and drinking.

These incidents don't appear to be part of any ongoing hostility though. According to Sullivan, the pit kids don't begrudge Harvard students their relative wealth or opportunity. Harvard students have even worked at Bread and Jams through the First-Year Urban Program this fall. What is most prevalent is a studied separation, with students and pit kids keeping their worlds apart. Harvard students trip to class rarely acknowledging their peers learning about life the hard way.

Are there skinheads in the area committing hate crimes? So far, the odds are against it. More palpable is the "crime" of unseeing, of dismissal and, like a hate crime, of intolerance. How many times have you asked yourself: Why can't they just get jobs? Can't the police get rid of them? What's wrong with them?

What students don't ask themselves is: What kind of illnesses are these kids dealing with? What family situations are they escaping from? Where can they go if they need help? There are a hundred-and-one programs directed at kids at Phillips Brooks House and none for the homeless youth in Harvard Square. While youth services exist in Cambridge, they are mostly daytime shelters. At night, most homeless youths must sleep on the streets. The Cambridge City Police reported last year that most violence in the Square was directed at the homeless by other homeless people. Youths, lacking a haven at night, are the most vulnerable targets.

It's easy for Harvard students, many of whom have overcome great obstacles in order to be accepted here, to look disparagingly at the pit kids' lifestyle and supposed "choices." What's hard is resisting the knee-jerk reaction to condemn instead of understand, to draw conclusions about character from outward appearances. There is clearly more to this story than skinheads and hate. As Sullivan said, "There are a lot of people at Harvard who want to help...but there a lot of people who want to turn their heads."

Meredith B. Osborn '02 is a social studies concentrator in Leverett House. Her column appears on alternate Fridays.

Read more in Opinion

LettersRecommended Articles

-

Two Truths and a LieFor my first column, we'll play two rounds of an ice-breaker called "Two truths and a lie." Spot the lie

-

Cambridge Targets Pockets of Hidden ViolenceTwo murders, 11 rapes, 165 robberies, 348 aggravated assaults. There were 526 violent crimes in Cambridge last year alone. About

-

Harvard Crime Surge Connected to Cambridge Increase10 days ago, at twilight, four teenagers approached someone affiliated with Harvard near Peabody Terrace, pushed him to the ground

-

Service Remembers Life of Homeless WomanAt 11 a.m. yesterday, nearly 60 people gathered at University Lutheran Church to commemorate the life and death of a

-

Murphy Fields Scandal-Related Questions at Press ConferenceThe post-game press conference was more crowded than usual following the Harvard football team’s season opening win over San Diego ...

-

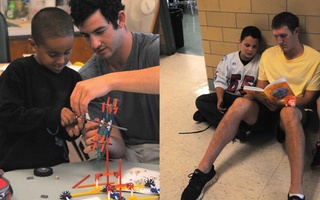

Baseball Spends Time with Local Elementary Students

Baseball Spends Time with Local Elementary Students