Donald Margulies' recent play Collected Stories rests on the foundation of a popular dramatic scenario: the formation of an engaging, vital and sometimes volatile relationship between two working artists. What sets Collected Stories apart from the rest is that Margulies filters this often unwieldy theme through a completely engaging, funny and provocative story. He first commands your attention, then challenges your intellect, as does the Huntington Theater Company's new production of his play.

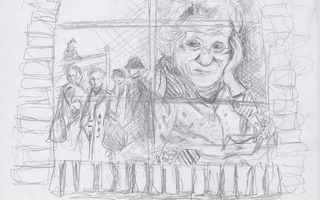

Collected Stories, a finalist for the 1997 Pulitzer Prize, is about a mentor-protege relationship between two women writers. Ruth Steiner (Deborah Kipp), a middle-aged writer living in Greenwich Village, takes on the overeager graduate student Lisa Morrison (Felicity Jones) as her assistant and tutee. Lisa is awed by the impressive Ruth, who has published a respected body of short stories and who embodies a long-standing New York literary tradition Though Lisa starts out as an insecure chatterbox, both women soon emerge as uniquely witty, charming personalities. Their interaction provides plenty of sparkling, funny dialogue, especially about the challenges and peculiarities of life as a writer.

With Ruth's assistance, Lisa begins to get her stories published, and what has evolved into a comfortable, friendly working relationship takes a new turn. Though Ruth admits that she is somewhat uncomfortable with Lisa's success, the tension doesn't really bubble to the surface until Lisa writes a novel based on her teacher's life, centering around a secret affair Ruth had in her youth with the legendary poet Delmore Schwartz.

Ultimately, what is most admirable about the play is that it does not provide obvious answers to the questions it raises. Writing a two-character work provides Margulies the opportunity to flesh out realistically complex personalities, and the dilemma that results from the course of their relationship has no easy solution. The play asks, who has the right to turn a person's life into fiction? Is Lisa's novel about Ruth's life an act of love or a "theft" of stories which she has no right to appropriate? The answers to these questions are further complicated by statements which Ruth makes early in the play about having a "need" to write certain stories, no matter whom they hurt.

Many of these issues come fully to light only in the play's well-developed final scene, which ends on a surprising, thought-provoking note. Margulies is careful to spend most of the play's duration developing an intimate, caring relationship between Ruth and Lisa, showing that two writers can interact positively, at least for a while. Because Ruth and Lisa seem to complement each other so well throughout most of the play, the emotional explosion in the end carries a great deal of power. Both characters are appealing in their own way, so the audience is confronted with a difficult challenge: whose side should be taken in this conflict of words?

None of these complexities would come across quite so eloquently without the accomplished performances of Deborah Kipp and Felicity Jones. Kipp, as Ruth, puts forth the perfect amount of droll wit in her early scenes to command respect, laughter and attention--she's casually captivating. In the second act, this bravado gradually transforms into insecurity about her position as a writer--an important change which Kipp portrays very sympathetically.

An even greater range of emotion is required from Jones as Lisa. Even though Lisa is already in her twenties when she first meets Ruth, she is still "growing up" throughout the play, both as a writer and an individual. Each scene requires her to be different person, a challenge which Jones handles gracefully. Her transition from a fawning grad-student with a teddy-bear backpack to an accomplished writer giving a speech at the 92nd St. Y is both striking and fluid. Jones' performance adeptly displays the conflict between Lisa's love for her mentor and her need to establish her own life as a writer.

Impressively, the play retains its stylish, literary sense of humor even in its intense last scene. "Life's too short for the New Yorker," Ruth quips truthfully to before an outburst of anger. Ruth and Lisa's jokes, like their writing, are at the root of their intimate relationship.

Ultimately what comes between Ruth and Lisa is a territorial conflict, but the material at stake--personal stories--is invisible. Though Margulies doesn't force the play into a statement of right and wrong, he does communicate the preciousness of stories. Lisa has followed the perennial piece of advice to "write what you know," but Ruth thinks that Lisa has taken this too literally by exploiting the story of her past. Although the rift in their relationship can be contemplated as an ethical dilemma, Margulies makes a stronger argument for the inevitability of literary inheritance. In the end, the play is less about moral principles than about the power of the written word--to bring people together, to unearth hidden stories, and, sometimes, to divide.

Read more in Arts

All Heroine, No HighRecommended Articles

-

Digging up 'Ancient History' in the Pool“Paradise.” “Aaaaaabsolutely.” “Paradise.” “Aaaaaabsolutely.” Beginning unassumingly, with the two characters laying in bed, Ancient History is a play that asks

-

Ginsburg Speaks At Law ReunionU.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg told 700 Harvard Law School alumnae on Saturday that it has been "grand"

-

TouchJoel Schwartz's last play, Mine Eyes See Not So Far, was a long tortuous examination of single character heightened by

-

Complex Characters Drive ‘Collected Stories’Steinbach’s authoritative performance carries the play, and though she could outshine many skilled actors, she is nonetheless held back by her comparatively underwhelming co-star.

-

World War II Espionage Thrills in “All That I Am”

World War II Espionage Thrills in “All That I Am” -

Dr. Ruth Talks Sex and Jeremy Lin

Dr. Ruth Talks Sex and Jeremy Lin