To the Editors of The Crimson:

Laurie Grossman's recent article ("California Contradiction," January 14) is a perfect example of how sympathy untempered by reason can lead to irresponsible conclusions. Her sympathy was aroused by observation during a Christmas stay in Southern California of the predominance of Mexicans in subservient, low-paying jobs. This, she says, is "slave labor."

I am from San Diego so I am in a position to confirm her observations. She is correct; people of Mexican heritage, both citizens and aliens, dominate the bottom of San Diego's socio-economic ladder. But that is not the whole of the story.

If Grossman had traveled down the coast thirty miles to the homeland of these immigrants, she might have understood why so many of them willingly cross the border for the opportunity to perform "slave labor." There, in Tijuana, she would have seen not workers picking oranges for a few dollars an hour, but people begging for food; not housekeepers living in the "slave" quarters of fancy homes, but wretched families living in cardboard shacks that wash away in the winter floods; not gardeners driving beat-up Chevy's, but beat-up human beings for whom the prospect of owning a car is a hopeless dream.

Unbelievably, the quality of life in Tijuana is high by Mexican standards. But for Grossman the only standard by which to evaluate the position of others is her privileged own.

This, to borrow a phrase, is "arrogance cloaked as humility." I do not question the authenticity of Grossman's concern for an underprivileged group. Indeed, I find it laudable. But when such concern is untempered by considered reflection it can lead to irresponsible conclusions, in this case the assertion that Mexican laborers are slaves. This assertion is insulting for three reasons.

First, it is an affront to those whose ancestors really were slaves and who still suffer the effects of that injustice. To compare the position of those who enter this country, often illegally, to find work, with the position of those who were forcibly brought here to be traded and sold like cattle, is not a comparison at all but an absurd rhetorical juxtaposition.

Second, it insults the employers of these people by implying that they are the moral equivalent of slaveowners. Would Grossman prefer it if, out of concern for the dignity of these "slaves" and her own troubled conscience, they were fired from their jobs and left to fend for themselves? Or, better yet, that the illegal aliens among them be shipped back to Mexico where there is greater equality of misery.

Third, it insults the "slaves" themselves to refer to them as such. Grossman unconsciously reflects the bourgeois liberal conceit that any standard of living which does not match the American middle class is worthless--the equivalent of slavery. This conceit is often expressed in terms of genuine sympathy and a desire for greater equality (though not at one's own expense), yet it inevitably carries an undertone of contempt: sympathy for the poor Mexican grounded in the judgment that his life is not worth living.

I am not calling for less sympathy but for more realism, which is too often misinterpreted as an apology for social injustice. It is easy to forget that most of the world does not come anywhere near the standard of living of even the lower levels of American society. For the people whom Laurie Grossman observed, American is truly a land of opportunity, a better place to live that the country they left behind. My guess is that they appreciate our country more than she does.

Read more in Opinion

Scoring at the BuzzerRecommended Articles

-

Grossman Discusses Israeli LiteratureIsraeli novelist and political activist David Grossman shared the stories that influenced his latest award-winning novel, “To the End of Our Land,” at a guest lecture Tuesday night.

-

A West Coast Spin-Off of Harvard University

A West Coast Spin-Off of Harvard University -

Harvard Law Review Increases Online PresenceThe Harvard Law Review will more than double the number of editors focusing on online content for the publication next year in an effort to expand its web presence.

-

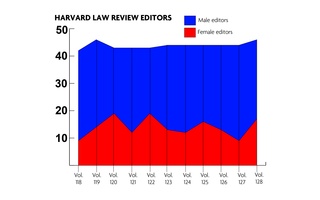

Number of Female Harvard Law Review Editors Nearly Doubled in First Gender-Based Affirmative Action Cycle

Number of Female Harvard Law Review Editors Nearly Doubled in First Gender-Based Affirmative Action Cycle -

Harvard Law Review Selects 128th President

Harvard Law Review Selects 128th President -

Coakley and Grossman Lead Democratic Candidates for Governor

Coakley and Grossman Lead Democratic Candidates for Governor