"Students," read the cryptic two-inch ad in last month's Crimson, "if you would like to go to Japan, Hong Kong, Sri Lanka, India, Nepal, Iran, Jerusalem, Morocco, and Europe, call this number:----."

Once in a blue moon the International School of America makes its existence known in such a mysterious manner. It is a 15-year-old program that travels around the world for a year by jet, carries a three-member faculty and 30 students, who live with native families enroute, and are given a full year's academic credit by most American universities, including Harvard.

Because the International School has tried to keep its low profile, few people, including most Harvard administrators, know anything about it.

When Karl Jaeger first conceived of the traveling school, he wanted it to be different from anything that had come before--so much different that an attempt to describe it simply would belie its uniqueness and, as the years have granted, its mystery.

Jaeger, a board member of his family's power tool company and "independently wealthy" as he is wont to say, decided to create an educational alternative to lectures and exams while an undergraduate at Ohio State. "I was looking for something beyond common experience," he explains, "and traveling around the world seemed a good place to start. Later as a grad student at the Harvard Education School, I put together a program for which I could find no precedent. I studied one special school that traveled by ship to various distant ports, but it seemed to me that more of the world could be explored by going by jet, and living not in a stateroom or hotel, but with native people the way they really live."

The result--a sort of grand multi-media functionally kinetic thesis--was a 27-student global tour, subsidized by Jaeger, led by Edgar Snow, author of "Red Star Over China." Though the first year's trip didn't get into China, its course impressed enough educators (especially those who grant academic credit to students) to warrant continuation.

Each subsequent year's program was headed by a similarly respected name in a particular field (Huston Smith in religion, Daniel Lerner in sociology, Gregory Bateson in anthropology) and followed an itinerary chosen by the leader. The structure of the academic side of the school has remained as Jaeger first conceived it: a theoretical investigation ("Utopias" under Smith, "Change and Modernization" under Lerner, "The Nature and Culture of Man" under Bateson) substantiated by first-hand experience and supplemented by an occasional book and periodic class meetings to tie the whole thing together.

But as subsequent years have shown, the academic side of the trip has been secondary to the trip itself: the knowledge gained through the school has not been anything studied formally so much as the result of experiences of the entire year. As Bateson put it, "I taught that year as I suspect most others in my place did. Since I believe studying systems of thought requires a rigorous background, I tried to give students an intellectual set of baggage to be filled up with suitable related experience. But after a point, of course, acquiring the baggage has to cease, and getting out and finding experience to fit has to begin. I gave them a way to understand, I hope, what they were seeing, and then let them go off on their own. Most kept coming back to discuss their impressions with me, but those who didn't, I would suppose, learned just as much."

Two or three class sessions a week are offered during the trip, but not required if a student thinks he has something better to do. A "paper" is required at the year's end, but the work has taken such form as a dance by one student who studied dance by one student who studied dance cross-culturally, and even a verbal essay on the benefits of following after one's own thinking and one's own desires.

Jaeger, from his present home in Bath, England, would be anxious to stress not the freedom of his school, but its formal structure, so as to preserve the legitimacy the first trip have done little to undercut. And indeed, the formal structure of the International School is as sound as it has always appeared. But it remains the informal aspects that give the school its curious and unequalled appeal.

* * *

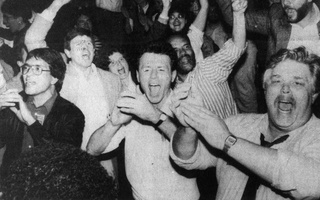

My introduction to the school's program--as a member of the Bateson trip four years ago--came at a three-day intensive "sensitivity session" at a mountain-top retreat on Hawaii's main island of Oahu. The Esalen Institute sent its leading counselor from California to help the 30 students of the school draw closer together, to form a cohesive bumper against the shocks of the different cultures the group would be moving through and living within.

But instead of diligently trying to follow the Esalen "let's be one, big happy family" credo, a part of the group decided to get drunk, watch the Hawaiian sunset, and go skinnydipping.

"I was disappointed," Jaeger reflects, "that unfortunate dissensions and power disputes within the group came to light so early in that trip. It was clear some people would simply do what they wanted to do." But, as he probably would not say, the structure of the school makes it possible for them to do it.

After a four-day paid vacation at a resort hotel on Waikiki ("I'll never be able to live this year again," said Jack, drinking mai-tais at the balcony of Jaeger's hotel penthouse, "so I'm not going to spend even 10 per cent of my time worrying about social interaction with the group or joining the group activities I don't want to join."), the school flew to Tokyo. Each student lived with a Japanese family to fulfill the school's philosophy of viewing the culture from the inside (watching from within the rice paper porch the gardener snip pine needles in the bonsai grove). Bateson and Jaeger also held daily orientation classes at their downtown hotel.

Read more in News

The Brave OneRecommended Articles

-

On Its 10th Anniversary, HUCTW Is Happy With HarvardLast year, Albert Carnesale's head was a common sight in Harvard Yard. Throughout the cold winter months, protesters representing the

-

Jaeger to Retire At End of June, Plans New StudyWerner W. Jaeger, University Professor and author of several well-known works in philosophy and philology, will retire on June 30,

-

Jaeger Service HeldFormer coleagues, students, and friends of Werner W. Jaeger filled Memorial Church yesterday afternoon for the funeral of the prominent

-

NEW PROFESSOR NAMED TO POST IN UNIVERSITYWerner W. Jaeger, formerly a professor at the University of Berlin, and since 1936 a professor at the University of

-

Still Waiting, Union Pens Letters to Top DeansMembers of the Harvard Union of Clerical and Technical Workers delivered signed posters and letters on Thursday to the offices of 34 administrators regarding the union’s months-long contract negotiation with the University.

-

HUCTW Praised First Contract

HUCTW Praised First Contract