{shortcode-9f8dcb2e533ffad2c95a4032ba4dc733f51ade7a}

{shortcode-8c0dd475ea3269f67b1a4d37d27db5cc232a1fc2}hen I was growing up, my grandpa used to quiz me on directions while he drove me home from school or basketball practice. “Are we going north or south?” he’d ask. “Can you tell me what street we’re on?” I almost never knew.

At his dining room table, he used to have me draw maps of our town, trying to coach the directional challenges out of me. While he corrected me with patience, all I could think was how useless it was: I have good visualization skills, I knew which way the sun rises and sets. I probably could have tried harder, done better. But I just could not understand why he cared. Not when I could just “plug it in.”

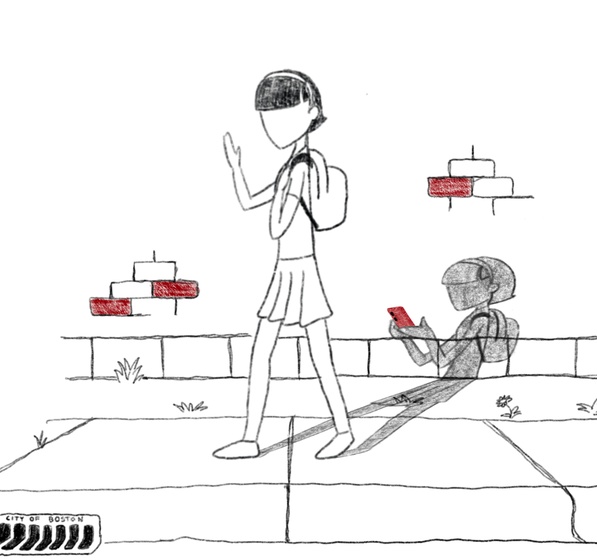

Instead of envisioning the roads, their intersections, and the landmarks on a drive, the world many of us imagine in our head is a blue arrow on a beige and yellow map. It is possible that we are more familiar with this digital abstraction of the world than its actual physical existence.

In my life, I have never known a world without Google Maps.

Every added technology is also an amputation, argued philosopher Marshall McLuhan in 1964. If the telephone extended the voice, it also cut off the need for good penmanship and letter writing. If GPS allows me to more easily navigate the world, it has also stunted my ability to find my own way.

In the same vein, social media and the broader internet extend our ability to retrieve information while amputating our reliance on our memory. With essentially all of human knowledge at our fingertips at all times, our brains are being rewired, decreasing our ability to recall facts and devaluing this type of recollection altogether. Rather than remember information, we remember where to find it.

Without lived experience in the previous system, however, it is difficult to understand the significance of what we’re losing.

My youngest sister is eight years younger than me. Our parents are older now, a little more tired, a little more lax, and she opened social media accounts on her school-issued laptop years before she got a phone.

I was a freshman in college when she turned eleven. When I went home for Thanksgiving that year, I paused when I saw her, realizing she had actually done her makeup as well (if not better than) I did mine. Looking at her perfect mascara, un-smudged eyeliner, and rosy cheeks, it dawned on me that an app had stolen something from both of us: an opportunity to connect. It was a moment I had looked forward to, one that called for the hard-earned wisdom and advice of an older sister. Instead, a stranger on TikTok told her how to grow up. And when.

TikTok was founded when she was four. She has never known a world without it.

Across the internet as well as the comment sections of Instagram reels, the same phrase keeps giving me pause: in real life.

The comments on funny videos in my feed are filled with users saying things like “I’m in real life tears,” or “This made me laugh IRL.” In 2020, the New York Times reported on how the phrase “Twitter isn’t real life,” was adopted as a mantra of pollsters and analysts during the 2020 elections to urge people to look outside of their echo-chambers, and remember that the platform is not an accurate mirror to society. Journalists who preach about body positivity and discuss the difference between “real bodies” and those over-edited ones on social media. Researchers warn against “real world impacts” and “real life consequences,” the implication being that the online world is “fake.”

But this framing encourages a false distinction between our online and offline lives. It creates a psychological split; we see ourselves as two people at once, with our social media personas representing an “escape from reality.” I can’t count the number of reels I’ve seen with captions like “consuming five different forms of media to minimize the chance of a thought occurring” as users sit surrounded by their screens, and I sit on the other side, using their content to do the same.

The distinction between worlds allows us to kid ourselves that the minutes we spend scrolling aren’t how we are spending our real lives. But what these worlds share first and foremost is our time. Five hours a day (the national average) on your phone is two and a half months a year. There is no real or fake life. There is only now. And how you spend it, counts.

On the same smartphone that lets me FaceTime my sister so we can be better connected over the physical distance that separates us, I find myself zoning out of our conversations, itching to open Instagram and start scrolling while she’s talking — lying to myself that I can focus on both.

Since its birth, we have pointed to social media’s ability to connect us to the people we care about as a reason to celebrate its role in our lives. But by now we all know how easily it can distract us from those very same people. The idea that online and offline lives are separate from each other, that one is less real than the other, is a dangerous fallacy, because it ignores the very real impact one has on the other.

The 2025 Netflix documentary “Bad Influence: The Dark Side of Kidfluencing” walks viewers through the alleged abuse that internet sensation Piper Rockelle and her “squad” experienced as “kidfluencers” managed by Piper’s mom. Throughout the interviews, parents and kids track how they slowly lost touch with who they were as they pulled cruel pranks, were put in uncomfortably sexual situations, and vied for attention online. Initially, they were able to mentally separate their internet personas from who they thought they were in real life. As they continued to play their online roles, however, they found the lines between the two worlds increasingly and dangerously blurred.

“Bad Influence” puts the spotlight on some extreme examples of the dangers of separating our online and real-life “selves.” Yet it is relevant to us all.

“Everyone is an influencer,” a friend suggested on a recent call. “If you have people following you.”

Online, most of us do things — make comments, share pictures, view content — that we would never do “irl” in order to cultivate our online presence. Tired of the constant need to perform, I recently tried switching from Instagram to the semi-outdated, slower-paced VSCO where I followed just a few friends from back home. For a couple of weeks, it was a nice way to stay in touch, to have a visual account of some of the more mundane happenings in their lives. But after a couple of months, if I am being honest, I found I was opening the app not to see their photos, but to see if anyone had liked mine.

To my friend’s point, even with private accounts and without the eyes of the world on us, social media quantifies our self-worth. The feedback loop instills a thirst for digital validation, but it doesn’t end online.

It is no wonder that we are in the age of the “Instagram face,” a time when women are told they cannot be beautiful unless they are indistinguishable from one another. Online, we are pressured to curate identities for public approval rather than encouraged to develop authentic, private selves through any amount of introspection.

We are not kind, to ourselves or others. We exile (or ridicule) differences and lose track of our own interests beyond what social media designates as “in.” This technology separates us, not only from our world, from our community and families, but from ourselves. And, in turn, this separation inhibits us from appreciating our or others’ individuality, even in the “real world,” where we continue to conform and assimilate to TikTok’s sterilized trends.

In 1959, sociologist Erving Goffman theorized that every human interaction is a performance used to create an impression, and that our identity is constituted by the summation of these performances.

The concept of an “irl” separate from life online creates a sense that we can be two different people at once: We can be cruel in one, but kind in the other. Aggressive online, and diplomatic in person. Silly on our stories, but uptight in our day-to-day interactions.

But the fact is, it’s all our Real Life: Our real time, our real connections, and our real beliefs that are being hijacked by something we call fake. As much as these platforms allow us to push away from others, they are, perhaps more dangerously, allowing us to distance from ourselves.

If all technology is also an amputation, it seems that social media has taken a part of our soul.

I’m not sure, though. I’ve never known a world without it.

—Magazine writer Aurora J. B. Sousanis can be reached at aurora.sousanis@thecrimson.com. Her column “Degrees of Separation” explores the relationship between technology and our growing self-isolation.