{shortcode-08377e0286ba479e6064c496f0124ec86da5fe44}

{shortcode-16f8ced088e32bb2d90bab8d4861646b946d7fa0}dward B. Childs didn’t intend to spend his life working at Harvard.

The longtime union organizer and Adams House cook came to campus at the behest of a friend in the dining workers’ union, who hazarded that Childs — already a seasoned organizer, though still a student at the University of Massachusetts Boston — might be able to help with their organization efforts. He intended to take a job for a semester.

“My semester that I was going to come here, I extended it for 50 years,” he says, cracking a smile.

Now retired from Harvard, Childs remains an organizer with UNITE HERE Local 26, the union representing the University’s dining hall workers. Over a half-century of organizing, he has seen the union through two strikes, participated in dozens of demonstrations, and traversed the globe in search of other workers’ stories. He arrived on campus as protests against South African apartheid played out, and he now guides workers toward contract negotiations amid a wave of student activism over Palestine.

Childs’ story is a patchwork quilt of Harvard and Cambridge histories, the threads of labor and social activism intricately interwoven. Over the course of several hourlong interviews on his home turf at Adams House, questions I pose about labor are inevitably stitched into answers about power, marginalization, and struggle.

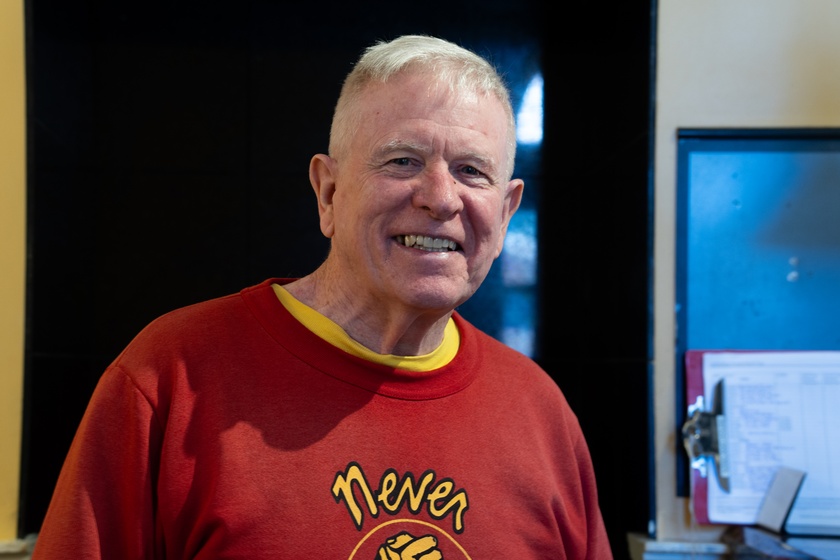

Each time I speak with him, Childs dons different versions of the same red sweatshirt with two clasped hands and the words “Never Surrender” emblazoned across the top — souvenirs from the union’s 1983 strike.

“Not too many people still have them,” he says, equal parts proud and wistful.

It’s a short, simple message: Ed doesn’t forget.

‘I Think You’re Supposed to Picket’

{shortcode-8c0dd475ea3269f67b1a4d37d27db5cc232a1fc2}hen I first meet Childs to discuss his role in Harvard’s labor movements, he is nothing if not prepared.

He arrives at the Inn at Harvard at 9 a.m. sharp, a legal pad full of meticulously compiled notes in tow. While I’ve just rolled out of bed, he has already been awake for several hours, attending meetings and talking to workers.

He didn’t cook and organize in these halls — Adams House is currently under construction — but there’s nevertheless a sense of homecoming as he maneuvers deftly around the tables to greet workers he has known for years. These people, after all, are part of the reason he remained at Harvard.

“One: I loved organizing. Two: I loved the people,” he says when I ask him what compelled him to stay at the University after that first semester. (After a moment, he admits a potential third: that the job prospects for a college math major who didn’t want to join industry weren’t particularly heartening.)

A Bostonian at heart, Childs grew up in Somerville’s Mystic Avenue public housing during the tail end of the 1950s union boom. His grandparents, who migrated to the U.S. from Ireland after the Irish Civil War in the 1920s, took union jobs at tire company BFGoodrich and candy manufacturing giant Necco. His father, a truck driver, was part of the Teamsters Union before becoming a cook at Buckingham Browne & Nichols School.

Childs himself began what he calls his first “legitimate” job in high school, at a local branch of the now-defunct First National grocery store chain. He participated in his first strike as part of the workers’ union soon after, when he says an employee was fired for insubordination during their lunch break.

“We had no idea what to do,” he says.

“Then someone says, ‘I think you’re supposed to picket,’ so we had a walkout,” he adds with a smile.

A few days later, all the workers were fired, he says.

Childs took — and walked out on — the job in a fractious political and social milieu. He grew up in a neighborhood of immigrants and people of color in still-segregated 1960s and ’70s Boston, and took a keen interest in burgeoning social movements around him. In 1970, several leaders of the Black Panther Party — including its chairman, Bobby Seale — were put on trial, catalyzing mass demonstrations in Boston. At the same time, pro-segregation group Restore Our Alienated Rights railed against integrating Boston public schools.

This tumult, alongside the ongoing war in Vietnam and the example of his hero Muhammad Ali, first led Childs to political activism alongside labor organizing. He joined the Workers World Party, a Marxist-Leninist organization dedicated to anti-war and anti-racism struggles, in 1970. He has remained a member ever since, using the Party’s framework for organizing and writing articles for its website.

“They were organizing events about the war and about the struggle against racism and the union struggle — putting them all together,” he says.

A few years later, after he was fired for mounting a unionization effort at his California Paints job, Childs infiltrated ROAR. The group, split into violent and nonviolent factions, had ties to the South Boston Marshals — a paramilitary group committing violence against Black people at the time. Childs used his secondary leadership role at ROAR to ascertain which homes might be targeted by the Marshals, and would then use activist networks to “get 100, 200 people to protect their homes before it happened,” he says.

ICP Group, which owns the California Paints brand, did not respond to a request for comment on Childs’ dismissal.

Per Childs, he ended up caught during a confrontation with one of ROAR’s leaders, Pixie Palladino.

“They came and attacked, and we charged them,” he says. “When we charged them, I didn’t know Pixie was going to be there. Pixie was there in a car, and she looked up to me and said, ‘You?’ ‘Yeah,’ I said, ‘Me.’”

‘Who Cares What Marx Said?’

{shortcode-21cc3534b02e5a90dd1b6e61be0fe28423896a7e}fter dropping his stint as a dishwasher at Sheraton Hotels and student at UMass Boston, Childs arrived at Harvard as a pot washer in 1975. At the time, there were four unions total on campus — a figure that has doubled in recent years. He quickly joined the fray, becoming a union shop steward after a year and then a chief shop steward two years later.

That year was particularly momentous for labor on campus. Harvard had just hired a new director of employee relations, sex discrimination complaints abounded, and multiple union contracts were set to expire.

The next decade saw Harvard dining workers through several workplace complaints over discrimination and a landmark set of contract negotiations culminating in a strike. When we met for our first interview, Childs’ recollections of worker walkouts proved almost encyclopedic: He arrived prepared with notes and names, making a marked effort to recall the union’s response on each occasion.

His first decade at Harvard saw several cases of alleged workplace discrimination. In 1975, the University came under fire for suspending Radcliffe dining hall shop steward Sherman Holcombe, who criticized management for discriminating against Black and minority workers. And in 1984 — a year after a landmark strike over the University’s decision to hire contracted workers — the union charged that the University excluded women from higher-paying cook positions.

Childs in particular recalled Passie A. Harley, a worker who was fired for tardiness in 1985. At the time, the union pursued a grievance alleging race and sex discrimination in Harley’s dismissal — a process Childs says “was like a brick wall.”

“They didn’t want to discuss it,” he says.

A University spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment about Harley’s suspension and the subsequent grievance.

{shortcode-72203594eee44e0b3682b24978f9459a68db3a4a}

The next day, Childs says, dining hall workers across campus walked out.

In situations like these, Childs says, walkouts and strikes helped tip the power balance between management and employees. This kind of struggle-centric thinking pervades his approach as an organizer: Profoundly influenced by his experience with the Workers World Party, his goal is to distill Marxist rhetoric into readily understandable tenets.

“Who cares what Marx said?” Childs says. “You get the concept of material interest. People’s material interest is the only thing.”

In this framework, he says, contract negotiations are inherently adversarial. And continual action — whether it be walkouts, strikes, or rallies — alongside training in organizing are necessities.

Childs points in particular to dining workers’ historic 22-day strike in 2016, when negotiations had stalled over pay increases and health care coverage. University officials finally agreed to pay full-time employees at least $35,000 a year and cover increased copayments for the duration of the contract. At the time, union president Brian Lang said that the union emerged from the struggle having “achieved every goal” it had set out to obtain.

“The only thing that worked was our strike,” Childs says.

“We said, ‘Our dish washers are much more powerful than the professors on campus on this issue,’ and the dish washers understood that,” he adds.

This dynamic unfolds in Childs’ ventures outside Harvard. In 1993, he found himself face-to-face with President of Cuba Fidel Castro — whom he refers to simply as “Fidel” — to discuss the union movement in both nations. He pauses momentarily during our conversation to scroll through his photos until he alights on the correct one, in which Castro lays a firm hand on a young Childs’ shoulder and stands back to appraise him. The photo used to hang in Adams, he tells me.

{shortcode-b94a626543bae60a5424237661a798d34f7b6c76}

But he is quick to say that the “highlight was meeting the workers,” not Castro himself. Besides, he adds wryly, many of the students he has shown the photo didn’t recognize Castro anyway.

‘The Struggle Continues’

{shortcode-16f8ced088e32bb2d90bab8d4861646b946d7fa0}d Childs is anything but elusive: Over the years, he has been a fixture in campus movements of all kinds. In his view, labor struggles have always transcended Harvard’s campus, inextricably linked to social justice movements around the globe. He has championed activism against South African apartheid, delivered pizzas to students sitting in for worker wage increases, and participated in pro-Palestine rallies. His name and words are strewn across articles from The Crimson dating back decades.

In the ’90s, Childs began supplementing on-campus activism with trips around the U.S. — and other nations — to document working-class lives via a TV show. He says his show, “The Struggle Continues,” aired on the People’s Video Network.

Before our last interview, he hands me a bag of S-VHS tapes with footage from his travels. Two “Iraq Sanctions” tapes document Childs’ 1998 trip to Iraq as part of an American delegation delivering medical aid to citizens amid U.N. sanctions. Another two labeled “Day of Mourning,” capture local activists’ speeches against settler colonialism on Thanksgiving, and “Stonewall Warriors” profiles performance poet Tina D’Elia and transgender activist-writer Leslie Feinberg. In the tapes, Childs plays journalist rather than activist, silently foregrounding others’ stories.

As part of his foray into documentary film, Childs visited Belfast during the Troubles, when the Irish Republican Army remained locked in a fierce struggle against British rule and its Irish proponents. During his visit, he says his friends played a recording of British soldiers shooting nearby and the IRA chasing them away. But interspersed with the audio were poems by Irish writers, including Seamus Heaney (an Adams dining hall frequenter, according to Childs) and Sean O’Casey, vividly capturing the Irish struggle for independence.

As the poem came on, his friends’ children all “stood at attention and listened,” he says — as did a few passersby. The gravity of the moment — everyone momentarily arrested by beauty and terror, murder put to meter — awed Childs.

“Did you ever see working people stop because there was a poem? Little kids stop because there’s a poem about their struggle? No, not in the United States,” he says. “No, that consciousness is not there.”

While filming in Belfast, he aimed to awaken this consciousness in an American audience — to demonstrate that the struggle in Ireland wasn’t solely a religious dispute, but a conflict over colonialism.

“I would do that by actually just showing shot videos of the streets in Belfast and the struggle, the brutality, and also show the economic benefits that England had,” he says.

To Childs, the ongoing war in Palestine is a similar matter.

“People today in the United States don’t understand that the war in Palestine is a colonial war, just like in Ireland,” he says.

These parallels are particularly acute this year. Today’s Harvard, in some respects, bears a resemblance to the one Childs encountered in his first years here: Then and now, several unions headed to the bargaining table amid student protests over international struggles.

The stakes are high. Workers across the University have been placed in an increasingly precarious position amid the Trump administration’s suspension of $2.2 billion in federal funding and crackdown on non-citizens.

Childs believes that the criticisms levied against Harvard — including allegations of campus antisemitism and critiques of diversity, equity, and inclusion programs — provide a “smoke screen” for the Trump administration to cut programs essential to working-class Americans.

Over the past few months, the federal government has slashed over $100 million in NIH grants to Harvard-affiliated researchers; the Harvard School of Public Health announced layoffs after researchers received stop-work orders.

“They go after these programs, and there’s not enough of movement to stop that,” Childs says.

In the meantime, workers are doing their best to maintain job security. At a Sunday rally, protesters from multiple Harvard unions called on the University to protect non-citizen workers from layoffs and detainment amid ongoing contract negotiations.

The day was blustery; union members drew their coats snugly around themselves as prospective first-years scurried past to join Visitas festivities.

I scarcely had to glance in the group’s vicinity to distinguish Childs. He greeted me enthusiastically, but stood back during the rally. Instead of speaking, he handed the microphone off to someone else, content to stand beside the people he worked with for decades.

Though he was easily a head above the crowd, his red sweatshirt was the dead giveaway — a stark scarlet branded with his signature slogan.

—Magazine writer Amann S. Mahajan can be reached at amann.mahajan@thecrimson.com. Follow her on X @amannmahajan.