{shortcode-65aab7b463c4d5561a69a8b43c990111a9531eee}

Content warning: Mentions of self-harm.

{shortcode-dd08abb0bb2b02bf4881baaa9fb305566107f8d4}he last time I cut myself was not like the other times. I didn’t need an outlet for a swarm of dysphoria — I’d learned how to control that by then. I wanted to hurt, not because I needed to make my pain legible, but because I felt deeply, unshakably, like I deserved it; like I couldn’t stand being myself; like even after running myself to the ground, dripping in sweat in front of the bathroom mirror, I needed to rip myself from my body.

The last time I cut myself, it was to punish. An X over my heart, rough faults carved down my stomach and my left arm.

***

Those scars have long faded, but the feelings haven’t.

At some point, I concluded that my default state was bad and guilty. If I was resting, I was guilty of wasting time and not working. If I didn’t finish everything I set out to do in a day, I was guilty of not being productive enough. If I cried, I was guilty of being weak. If I turned to others for support, I was guilty of being a burden. If I didn’t do something I thought someone would want, I was guilty of not being enough. If I wasn’t perfect, I was wrong and bad.

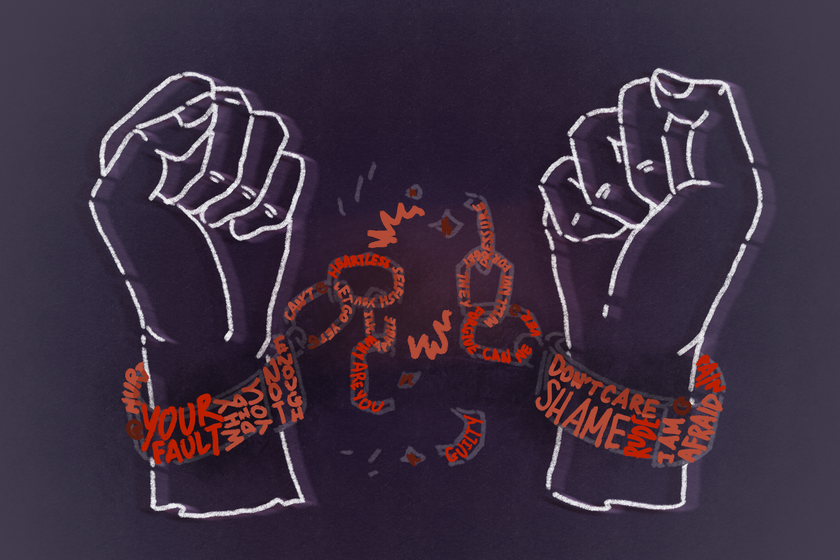

Even with the progress I’ve made in years of treatment, I’ve continued to relentlessly prosecute myself for everything that could possibly be construed as a transgression. I even deemed myself guilty for the emotional abuse and sexual trauma I have endured. The lines blurred; self became action and inaction. My being became not just a conglomeration of transgressions but a transgression itself.

“You know, it’s really interesting,” my psychiatrist says to me one session. “Most of the people I work with, they’re engaging in behaviors that are harming people around them, and they can’t see that, and my job is to get them to understand what they’re doing and to stop. But with you,” she pauses, searching for words. “It’s like the opposite. You’re a good person. You’re doing everything right. And I feel like a lot of our work is centered around trying to get you to see that.”

You’re a good person. “Yeah, um.” I nod and laugh drily. “Yeah, I think that’s the thing I’ve struggled most consistently with.”

For the most part, I don’t go about my days actively thinking I am a bad person. But I can’t control when the thoughts arise — and when they do, they are relentless. In my most vulnerable moments, it all comes pouring through the cracks. I am unclean; I am irreparably flawed; I am not enough and too much all at once; I am unlovable and dysfunctional and incompatible with the world.

***

The scrupulosity isn’t all bad. Without the constant self-flagellation and self-surveillance, I likely would not have pushed myself the way I did in high school, would not have scored the same chances of coming to Harvard. Even once in college, when I was in the worst of my depression, I dragged myself to classes and completed all my work on time because those were the “right” things to do. I make a point of proactively communicating with people, because I worry that not doing so will make me a “bad” friend or colleague or student. Some may call it being too morally rigid. I call it a tool for survival — both a buoy and a vague grasp at feelings of order and control.

Maybe that’s why it’s so hard to let go. It’s a working system, and one that has gotten me this far. Who will I become without it? Who will I become when I remove what I think has kept the caustic wrongness at bay?

***

“There’s this huge ball of amorphous junk and hair in this pipe that’s causing it not to drain and causing you not to get fresh water … and it has your name on it, it has your own shame on it, it has your own past mistakes written on it.”

I’m listening to a podcast by spirituality influencer Gabi Abrão that a friend recommended during one of our conversations about our mental health. Titled “In a world addicted to guilt, find the land of Innocence and Forgiveness,” the podcast feels like sitting down with a friend at 2 a.m., wine-drunk and philosophizing the best your young adult minds can. I cling onto Abrão’s every word as she talks about how immersed we are in guilt, how it feeds on a mistrust of yourself and others, how it inhibits your ability to live your fullest life.

“We’re only guilty of literally navigating our bodies incorrectly, which is just like a frickin’ baby. We never really stop being kind of babies, we’re always learning, we’re always navigating new things.”

Lying in bed, eyes closed, face mask cooling my skin, I imagine Abrão’s words washing over me, cleansing me, lifting all the dirt and grime and pain and trauma from my body and carrying it gently away. When I open my eyes, I think I understand again what it means to feel light.

The podcast did not fix me. The point of obsessions like these is that they fly in the face of reason. They thrive on gut feelings, deeply-held beliefs, guilt, shame. I cannot yet fully eradicate them; sometimes I wonder if I ever will.

But I am learning how to soothe them.

***

Sometimes, I stare at my naked body in the mirror before I shower. I notice every mole, every divot, every asymmetry. If I look hard enough, I convince myself I can see my scars, too: the X over my heart, the slashes carving up my stomach, the harsh fault lines on my left arm.

We never really stop being babies.

I step in the shower. I let the water run over me.

—Magazine writer Kaitlyn Tsai can be reached at kaitlyn.tsai@thecrimson.com. Tsai was a Magazine Chair of The Crimson’s 151st Guard. Follow her on Twitter @kaitlyntsaiii.

If you or someone you know needs help at Harvard, contact Counseling and Mental Health Services at (617) 495-2042 or the Harvard University Police Department at (617) 495-1212. Several peer counseling groups offer confidential peer conversations; learn more here.

You can contact a University Chaplain to speak one-on-one at chaplains@harvard.edu or here.

You can also call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255) or text the Crisis Text Line at 741741.