{shortcode-cd23bfe4ea9f42cad5270ba59b7849eae6892381}

{shortcode-dd08abb0bb2b02bf4881baaa9fb305566107f8d4}he American cross-country train is dreadful transportation. It is almost always too slow to plausibly be the most efficient journey. It is almost always too expensive to attract those simply trying to cover distance. It is almost always too bare to attract a significant tourist class. In a country dominated by cars and planes, the train occupies the proverbial backseat.

The cross-country train is, however, a profoundly American cultural space. Every person aboard the train has a reason to exist there, rather than on a more convenient form of transit that would probably already have them at their destination. These reasons need not be logical or honorable, but they are always personal, often zany, and, in the words of the journalist Gay Talese, evoke “the fictional current that flows beneath the stream of reality.” The cross-country train ride is a 60-hour American life; a couple hundred human mayflies buzzing around a dozen cars until, stop by stop, they each die off.

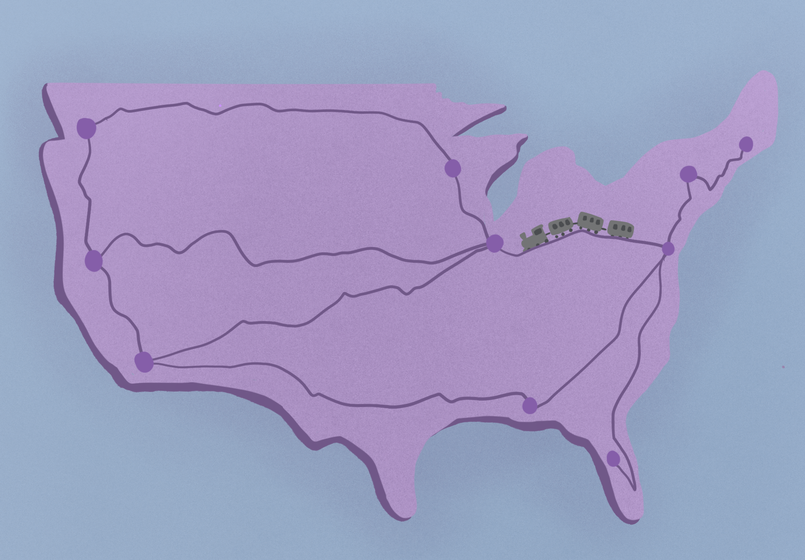

Like any dutiful writer aspiring to understand the American experience — Didion, Kerouac, Steinbeck, and more — I hoped to take the pulse of the country. So, this July, I took Amtrak’s Southwest Chief from Chicago to Los Angeles as part of a larger train trip around the country. I lived as a railway mayfly.

Like a proper wanderer, I packed only what fit into a backpack: three changes of clothes, a lightweight blanket, baby wipes, two books, and a deck of cards. My seat was in coach, the last car on the train, but I spent most of my day in the observation car, conversing with my fellow travelers. I imagined myself as a receptacle for their stories, a roaming raconteur recording the stories of these characters.

And there were characters.

The first night, I spoke with a middle-aged Palestinian American woman for four hours in the observation car. As we moved from the corn fields of Illinois and Iowa to the corn fields of Missouri, we talked — rather, she talked to me about — Israel and Palestine, relationships, Islam, family, Harvard, and more. The conversation devolved as she got progressively more wine drunk, but nonetheless, I didn’t depart until she began a similar inquisition of a young Amish man. The woman and I exchanged phone numbers; she texted me weeks later to wish me luck in college.

My seat partner was a few years older than me; he was traveling to Arizona to pick up his girlfriend before they drove to Minnesota for graduate school. His kindness and passion were evident. He spoke with fervor about environmental protection efforts in the forest near his hometown, and listened attentively as I described my love of journalism. He got off the train as I slept; I never got the chance to say goodbye.

I spent the most time with a young woman just a year or two older than me. She’d been hospitalized until age seven, at which point her mom sprung her loose, homeschooling her while traveling the entire lower 48 states along with her siblings. She graduated college at 18, became a hospice nurse in the Midwest, and became pregnant 18 months later. She was returning to L.A. on my train to raise the baby — 20 weeks to go — with her family. We talked for hours upon hours and played hand after hand of cards. When she got off the train in Riverside amidst an evening bout of morning sickness, I carried her luggage to the elevator. Now, we check up on each other every couple of weeks via Instagram.

Not everyone was lovely. I woke up at 7 a.m. on the second day to a couple’s full-fledged argument in the seats behind me; I heard later that both were booted off somewhere in Kansas. As I walked to the restroom on the second day, I heard a man aggressively snort something as his seatmates laughed; white residue was still visible on his nose when I passed. On the last day, I photographed the sunset for a guy in legal trouble he wouldn’t reveal; he said the train was the only way he could escape probation without anyone knowing.

Even the train and its attendants felt like accessories to a larger narrative. The train was delayed 14 hours by virtue of six stops: one for a tornado, two for flooding, two for broken locomotives, and one because every single conductor aboard had worked the maximum time allowed by law. These conductors initially seemed as much a part of the vehicle as the spinning pistons, but as our lack of progress eroded their uniformed facade. By 1:30 a.m. on the second night, two of them sat in the dining car with me and a few other passengers, joking about the delays, but also about family, the road (or tracks), and home.

It occurs to me only now that I was not so distinct from my fellow travelers as I would have liked to believe. What must I have seemed like? An 18-year-old, Harvard-bound student traveling to nowhere in particular, carrying Rilke’s “Letters to a Young Poet” and shuffling playing cards for hours on end? In trying to interpret the characters of railway life, I was myself a character. My undertaking, my presence, made me just as zany as anyone. This, I think, is as good a representation of America as you’ll find anywhere.

Fifteen minutes before the train finally arrived in Los Angeles, a conductor found me in the observation car. He’d seen me carry my friend’s luggage to the elevator an hour before and came by to tell me, “You did a good thing.” He passed me two mints and departed before I could thank him. I haven’t forgotten.