{shortcode-8ab35b879844af043fa2f5bbf6e9489ac63ad20f}

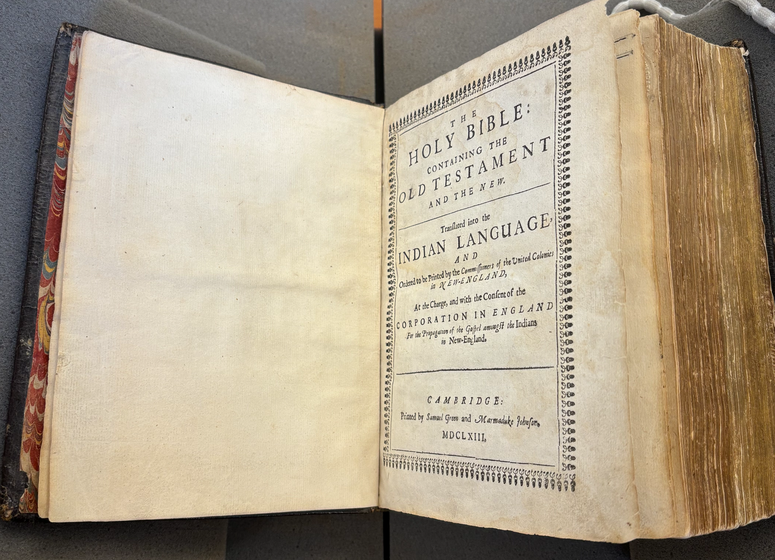

{shortcode-dd08abb0bb2b02bf4881baaa9fb305566107f8d4}he first Bible published in the Western Hemisphere was printed in Harvard Yard.

Deep in the basement of Harvard’s Indian College, John Eliot worked for 14 years to translate and print the Bible. Completed in 1663, Eliot’s Bible was written in Wôpanâak, the language of local Native American tribes.

Eliot commended the British throne for sponsoring this effort through the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England. Praising the support of Prince Charles in the Bible’s introductory letter, “Publications also of these Sacred writings to the sons of men,” Eliot wrote, “is a work that the Greatest Princes have Honoured themselves by.”

The production of this Bible was enmeshed in a broader Christianizing mission targeting Native Americans. To publish a Bible targeted towards such a “People without Law, without Letters, without Riches, or Means to procure any such thing,” Eliot wrote in the letter, “puts a Lustre upon it that is superlative.”

Although the Bible bears his name, Eliot did not work alone. In the 14 years it took to write this Wôpanâak translation, he worked with many Native Americans who spoke English alongside their native tongue. Interestingly, some linguistic inconsistencies in the Bible can be explained by the multitude of translators working on the project, who may have spoken different dialects, explains Norvin W. Richards III, a professor of Linguistics at MIT.

When Eliot was working, “there had already been these plagues which had killed off horrifyingly large portions of the Wampanoag population. Lots of Wampanoag had removed to the so-called praying towns, these towns that were founded for Christianized Wampanoag,” Richards says. “In a situation like that, you’re going to get multiple dialects.”

Indeed, the Eliot Bible was printed in a time of much social upheaval for Native Americans along the eastern seaboard. But as Linford D. Fisher notes in book chapter, “America’s First Bible: Native Uses, Abuses, and Resuses of the Indian Bible of 1663,” Eliot was so consumed by his ministerial duties that he likely never would have finished the Bible were it not for Native translators — first a man named Cockenoe, then John Sassamon and Job Nesutan. He was also aided by Native printers, specifically Wowaus, all of whom remain uncredited in his Bible.

At Harvard’s Indian College, which housed a total of five students before its closure, Native students brought knowledge of their own languages to campus, despite formal instruction in English. In 1660, commissioners of the United Colonies even observed that Wôpanâak was spoken with such prevalence that there was “no fear or danger of their forgetting it.”

The written form of Wôpanâak, initially introduced by British colonizers, was given further life by Wampanoag people writing contracts, deeds, and wills — sometimes as a way of holding colonists accountable after instances of broken oral treaties. At peak literacy, only about 30 percent of Christian Indians in Plymouth colony could read Wôpanâak, a primarily oral language. Yet, history contains no record of Wôpanâak being spoken after 1833, 170 years after Eliot’s Bible was first published on Harvard’s campus.

Struck by visions of the Wôpanâak language returning, Jessie Little Doe Baird, a member of the Mashpee Tribe of the Wampanoag Nation, founded the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project in 1993. Baird worked on the project at MIT before graduating with a master’s degree in linguistics in 2000.

Richards, who got involved in Baird’s project when he joined MIT’s faculty in 1999, notes that within the field of linguistics, this was a bold project. While some, like Richards, believe that linguists should both learn from and preserve endangered languages, others view their role towards languages as analogous to “hospice care for human beings.” When he heard Baird’s project to bring back a language with no active speakers, Richards recalls thinking, “it was a crazy idea.”

The success of the WLRP has been aided by the rich historical record of written Wôpanâak, which is the Native language with the most written documents on the continent. Central to this canon is the Eliot Bible, to which translators can compare the King James Bible to bear much linguistic fruit.

For example, Baird explains that there is no Wôpanâak word for hell. Instead, translators used “chepiohkomukqut,” which means “house of heads without a brain.” This is in line with the Wampanoag belief that the soul resides in the brain, and, as such, the worst punishment would be to live eternally with an empty head — and thus without a soul.

Today, the WLRP teaches Wampanoag Nation members Wôpanâak through community language programs, a Mashpee Wampanoag school, and immersion classes.

Yet, the work of the WLRP will never be over. Even with children now growing up learning Wôpanâak alongside English, it will be a “constant battle” to keep the language alive, Richards says. Still, the progress of Wôpanâak stands strong in the context of some estimates, Richards cites, that 50 to 90 percent of the world’s languages are soon to disappear.

Understanding the success of Wôpanâak reclamation in the context of the Eliot Bible that made it possible complicates the picture. The Bible created at Harvard to Christianize Native Americans and erase Wampanoag culture now provides a foundation for Wôpanâak linguistic survival.

— Magazine writer Thor N. Reimann can be reached at thor.reimann@thecrimson.com.